Having decided I wanted to write about a young female spy in London on the brink of World War Two, I knew I’d be taking a deep dive into research for the project. This ‘work’ (though, happily, it never really felt like that) took me to London, Oxford and other sites in the UK, visiting archives, museums, houses, pubs and parks. As I immersed myself in these places, conjuring character, events and the specific historical era, I read some influential novels to lend flavour to my journey and add inspiration to the writing process.

William Boyd’s Restless

This novel inspired me to really plumb the depths of the psyche of a female spy. Boyd’s enigmatic Eva is a Russian recruited to the British intelligence service after her beloved brother’s death on the brink of the Second World War. This emotional cataclysm drives her through a story that is full of energy, pace, as well as fascinating psychological insights into what made spies tick. The novel deftly weaves two timelines—wartime London and 1970s Oxford—to bring about a fascinating moral reckoning. Boyd presents the reader with a complex, resilient, brave and fallible lead character, one who challenges the traditional masculine space of literary espionage.

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer

I have never anything quite like The Sympathizer. I say “read”, but in fact I first consumed this Pulitzer-Prize winning novel in audio, with Francois Chau narrating, which is an absolute delight. Chau’s rich, mellifluous voice gives a wearied yet determined detachment to this story of a North Vietnamese mole, who after the fall of Saigon remains embedded a South Vietnamese community in exile in the United States. This novel is mind-blowingly good, a pyrotechnic demonstration of style, mashing up a range of fictional genres, including mystery, meta-fiction, comedy and, of course, espionage. The Janus-like nature a spy’s character, the moral ambiguity of which the novel works to reflect back to the reader, is captured succinctly in the opening lines: “I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds.” The Sympathizer is brilliant.

Kate Atkinson’s Transcription

Having read several of Kate Atkinson’s Jackson Brodie crime novels, I was looking forward to getting stuck into Transcription, the third in her trio of novels set in World War Two London which includes Life After Life and A God in Ruins. Transcription goes deeper into the role of MI5 during the war to explore the personal cost of subterfuge and espionage during the period. The novel demonstrates Atkinson’s masterful storytelling—this is an exquisitely crafted literary thriller partly inspired by the story of Eric Roberts, an MI5 officer who spent the war masquerading as a member of the Gestapo to trick British fascists into revealing their treachery. Atkinson has always used her fiction to canvas bigger ideas; Transcription is a deeply thoughtful, wry and always intelligent novel, with a fascinating backdrop, rich with historical detail, real-life figures and events woven through the story.

Sebastian Faulks’ Charlotte Gray

This novel is a gorgeous homage to France, as well as effortlessly fictionalising the role of a courageous female spy who is assigned to work for the French resistance deep in Vichy France in the midst of World War Two. What I love so much about this work is the delicate balance between the research (Charlotte Gray is loosely based on Nancy Wake, aka “The White Mouse”, a New Zealand-born Australian nurse highly decorated for her dangerous espionage work for the SEO in occupied France), the lyricism of the language and narrative, and the meditation on the nature of memory, truth and history: “Memory is the only thing that binds you to earlier selves; for the rest, you become an entirely different being every decade or so, sloughing off the old persona, renewing and moving on. You are not who you were, he told her, nor who you will be.” And the 2001 film adaption with Cate Blanchett as Charlotte Gray is terrific.

Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent

The Granddaddy of spy thrillers, Conrad’s famous novel (and latterly infamous, given it inspired several real-life acts of terrorism) is considered one of the most influential works in the literary espionage canon. It’s not hard to see why: there is a prescience to Conrad’s story that has not diminished since the work was first published over a century ago. Based on a real-life terrorist act, the novel concerns Adolf Verloc, a businessman living an unremarkable life in London in 1886—except that he’s also an agent provocateur for an unnamed embassy (though we can deduce it is Russia). When Verloc gets a new handler, Mr Vladimir, he’s instructed to committed a large-scale attack on the Greenwich Observatory. The intentions of this terrorism are clear: Vladimir believing the British government are soft on communists and anarchists, hopes the resulting public outrage will force those in power to adopt repressive civic measures. Reading The Secret Agent today, in the aftermath of Trump and Brexit, along with a resurgent and belligerent Russia, you can’t help feeling its warnings about state interference is as relevant as ever.

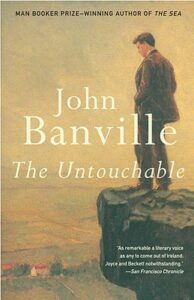

John Banville’s The Untouchable

I think this is an almost perfect depiction of the mercurial personality of a spy. It is also a sophisticated and exquisitely rendered work of literary fiction—one I’ve gone back to read several times to savour Banville’s prose. Banville’s celebrated roman à clef is narrated by Victor Maskell, an art historian, Soviet double agent and closeted gay man. This character is based on notorious Cambridge spy, Anthony Blunt, who for decades evaded detection as a Russian mole and maintained an illustrious career as a professor of art history; he was even appointed as Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures. Banville is said to have been inspired to write the novel after watching Blunt’s interview with reporters in which he revealed his true identity. A small secret smile was seen to pass over Blunt’s lips—a hint of his confidence, his menace and his sheer audacity—which fascinated Banville. I love this anecdote as it demonstrates how the smallest elements of human nature can be seeded to grow expansive literary portraits of complex people.

***