As I type this, a new film has been released which offers a backstory into the motivations of the Disney villainess Cruella de Vil, a character who needs no introduction (or even, some might say, explanation) but has been given one anyway. I haven’t seen this new film, Cruella, which stars Emma Stone and sets itself up as a pseudo-prequel to Disney’s live-action 101 Dalmatians film from 1996, which starred Glenn Close as the diabolical, piebald, puppy-stealing termagant. I probably won’t see the new film (simply because I’m not very interested in Disney’s live-action remakes and such), but I’m not writing this to knock it. All I can say about it is that I’ve noticed that, in preparation for or perhaps inspired by its release, many have taken to watching or rewatching Disney’s original 1961 film. To which I say: good.

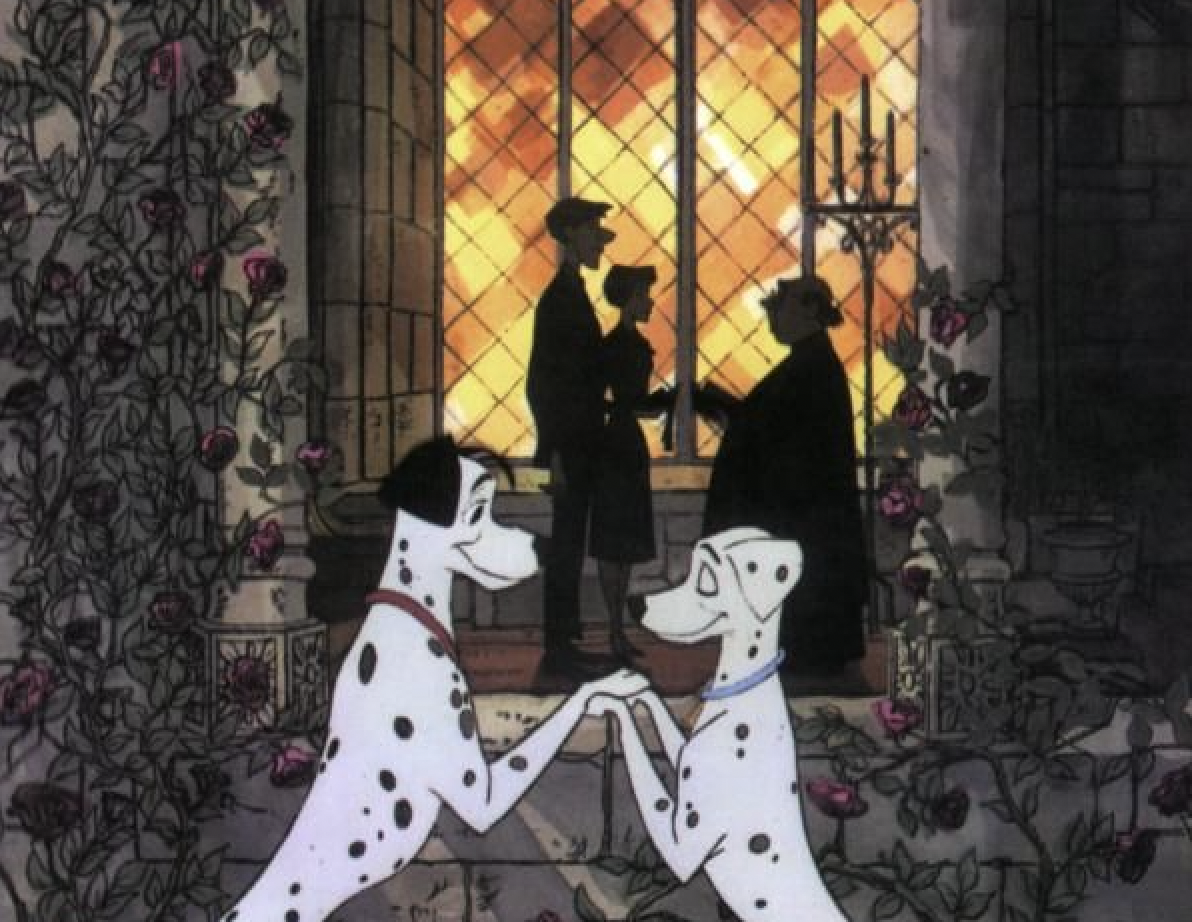

One Hundred and One Dalmatians (which IS a crime film) is a timeless joy, and an aesthetic marvel. If you have seen it (or even if you haven’t) you probably know the gist, but here’s a deeper dive. The film is set in London in 1958, and tells the story of an affable dog named Pongo (voiced by Rod Taylor) who wants to start a family, and so concocts a plan to set up his human, a musician named Roger Radcliffe, with a young woman named Anita, who (more relevant to Pongo’s interests) just happens to own a beautiful female dalmatian named Perdita. The pairs fall in love and settle down together in a neat row home near Regents Park (with a housekeeper known as “Nanny”), and it’s not long before Perdita gives birth to puppies: fifteen.

But when the puppies are born in the wintertime, Anita is visited by an old acquaintance, Cruella de Vil (incomparably voiced by Betty Lou Gerson), who attempts to buy the puppies to have their skins made into fur coats. “My only true love, darling,” she tells Anita re: furs. “I live for furs, I worship furs.” But the Radcliffes and the Pongos refuse to hand over the babies, and so Cruella hatches a plan to steal them: getting the material for her coats as well as revenge.

When the Radcliffes and the Pongos realize that their puppies have been dognapped, the humans turn to Scotland Yard. But Pongo and Perdita instead turn to the dogs of London, spreading the word and asking for assistance through a continental barking chain called “The Twilight Bark.” Dogs from all over the country pass on the message, until word reaches a group of animals who believe they know where the puppies are.

And so Pongo and Perdita must trek out of the snowy city and across the freezing moors to save their children and reunite their family. In the meantime, Cruella’s henchmen Horace and Jasper have hoarded an additional eighty-four baby dalmatians, for a total of ninety-nine, all of which she intends to kill to turn into coats. And so the Pongos decide they must save everyone, embarking on an enormous, and almost-impossible, journey countless miles back home with a group six times larger than the one they had anticipated. And they must do this while evading Horace, Jasper, and even Cruella herself, who are all enraged and determined to capture the dogs, once and for all.

Even though the film is set in the contemporary world (rather than a vague historical aesthetic or in a fantasy land), there is a kind of fantasy embedded in it.In my opinion, One Hundred and one Dalmatians is one of the most wonderful films ever made, and one of the most exquisite animated features ever produced. Aside from its more obvious delights (so many dogs! so many puppies!) and its powerful conflict with an (evidently) unforgettable villain, it’s primary, obvious locus is extremely satisfying: the film centrally features a family (human + dog) which can’t stop growing: when the film starts out, it is a family of two, then it expands to five, then to twenty, then to one-hundred and four. Even though the film is set in the contemporary world (rather than a vague historical aesthetic or in a fantasy land), there is a kind of fantasy embedded in it: when one-hundred-and one dalmatians finally show up in Roger and Anita’s home, they are thrilled to see their own dogs but agree to adopt everyone! There is a boundless enthusiasm and can-do spirit embedded in the film all along, but it crescendos in this ending: how many children (and indeed parents) watching this conclusion didn’t wish that they could do this very thing: adopt all the dogs in need of a home without worrying about space, money, resources, or time?

One Hundred and One Dalmatians is very much about the modern world—and the lines of communication and broadcasting that differentiate this era from previous ones.I suspect this unrealistic fantasy ending is a contributing reason why, when the film was released, it was immediately thought of as a children’s movie as much as, say, Cinderella, despite its rather disturbing stakes (that and animated films, especially Disney animated shorts and features, were always, always marketed as “family” entertainment). But there is a kindred spirit running through these films. In One Hundred and One Dalmatians, the vanquishing of an evil witch makes the tone rather fairy-tale-like, for a moment.

Wrote Howard Thomspon in The New York Times upon the film’s release, “The dogs are cute as can be, and the kids, especially the younger ones, should love them if—if they can take a female villain who makes the ‘Snow White’ witch seem like ‘Pollyanna.'” Like many Disney films, I’m not entirely sure that One Hundred and One Dalmatians is a kid’s movie at all (as a young child, I was too terrified of Cruella De Vil and her intentions to make it past her first appearance, and so really only watched the film for the first time as a teenager). But the buoyancy of its impractical ending goes a long way towards tying its thematic and artistic merits together, in a unique thesis.

The film, whose scenery is made up of inky line drawings, stands as a foray into a new style for Disney, one that moved away from the sensibility of its princess stories (even Sleeping Beauty, which experimented with a much more angular, illustrative animation style than the films which came before) and began to explore various modalities of twentieth-century life.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians is the first Disney animated film set definitively in the contemporary moment in which it was made, just three years before the film itself was released—and just two years after the publication of the novel on which the film is based, the 1956 story The Hundred and One Dalmatians by I Capture the Castle author Dodie Smith. With the exception of the amorphously Gilded Age Dumbo and the definitively Gilded Age Lady and the Tramp, Disney had not made a film set in the twentieth-century, and at that, never one set in its own time.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians is as much of a story about dogs as it is a story about media and entertainment: it’s full of contemporary technologies and communication vehicles, from phonographs to televisions sets. Pongo even attempts to gauge feminine beauty from fashion magazines so he might set up Roger with an attractive human. Advertisements for a dog food called “Kanine Krunchies” air on TV and light up billboards throughout the city. The Radcliffe-Pongo Dalmatian puppies love watching television every night and their favorite program is a serial Western, the adventure of a righteous dog named Thunderbolt who is pursued by a horse thief. When Horace and Jasper are guarding the dognapped dalmations, they are tuned into a game show called “What’s My Crime?” in which a panel of various guessers have to guess unusual crimes once perpetrated by various criminals—and this show directly references the actual 1950s-era television show “What’s My Line?” which has the same premise (except with a panel of guests guessing a contestant’s unusual occupation, rather than crime).

One Hundred and One Dalmatians is the first Disney animated film set definitively in the contemporary moment in which it was made.One Hundred and One Dalmatians is very much about the modern world—and the lines of communication and broadcasting that differentiate this era from previous ones. Yet modern innovations are unable to help recover the puppies. The dogs have to use their chief communication invention, which is veritably ancient: a barking chain. As such, One Hundred and One Dalmatians presents “community” as the most crucial structure of modern—any—society. And this, by the way, is an inter-species community… even aside from the humans Roger, Anita, and Nanny who will do anything for their dogs, and the countless dogs who assist them, Pongo and Perdita are aided in their quest by a goose, a cat, a horse, and several cows.

The most impressive scene in the film is the “Twilight Bark” sequence, in which dogs everywhere immediately rally, barking messages to one another in the night. Towards the end of the sequence, the camera pulls out over the entire city of London, brightly-lit with electric marquees, and playing diegetically over this image is the sound of every dog in that area barking loudly, producing a cacophony so noisy and mottled it causes many agitated humans to yell back at them to be quiet.

As the Pongos move from London to the countryside of Suffolk (where their puppies are being held at Hell Hall, a decrepit estate owned by Cruella herself), they are personally directed or escorted by a Great Dane in Hempstead, an elderly bloodhound at Withermarch, a “helpful, ‘Colonel Blimp’ sheepdog” (in Thompson’s words) at Hell Hall, a collie at a dairy farm just beyond, and a labrador at Dinsford. Indeed, the best thing about One Hundred and One Dalmatians is the animals, and how they demonstrate a capability far beyond human capacity, for eschewing the trappings of modern life. “The humans have tried everything,” a helpful Great Dane tells his friend just before sounding the first alert along the Twilight Bark. “Now it’s up to us dogs.”

Modern technologies are unable to help catch Cruella de Vil, who has been vetted by Scotland Yard and deemed innocent. “Imagine a sadistic Auntie Mame, drawn by Charles Addams and with a Tallulah Bankhead bass,” Thompson wrote in his New York Times review. But she is a complicated villain, because she has one foot in the modern era, and one foot in precisely the kind of fairy-tale aesthetic One Hundred and One Dalmatians mostly leaves behind. Thompson’s description is conveyed via three specific cultural touchstones, but Cruella is more timeless than by being an amalgam of these figures: as I’ve said, she is, plain and simple, a witch. Witches kill. Snow White’s witch tries to kill her. Sleeping Beauty’s witch tries to kill her. And Cruella de Vil (just look at her name), wants to kill, too.

Like Snow White’s witch, it’s done in the name of vanity. But rather than simply wanting to be “the fairest of them all,” Cruella cares about the world of high fashion. In Dodie Smith’s book, her obsession with furs leads her to marry a furrier. She is an idle, upper-class, old-moneyed lady with a longing for glamour. But she’s also the most ancient variety of villain possible. This is why the dogs can best her.

A discussion of how One Hundred and one Dalmatians plays with its contemporary moment and thematic lineage would not be complete, though, without dwelling on its actual design. One Hundred and One Dalmatians was incredibly challenging to produce, and the film was only made possible through the innovations of the animator Ub Iwerks, director of special process at Disney Studios, who modified a Xerox camera to transfer drawings directly to animation cels, eliminating the process of re-inking the drawing on those cels, which saved tremendous time and money when it came to animating so many distinct dogs. The film’s art director, Ken Anderson, decided that he would also used the Xerography on the paintings for the film’s background to experiment with a new look, which had been inspired by the British cartoonist Ronald Searle, who was famous for particularly inky line drawings.

Walt Disney himself did not like the aesthetic that Anderson, and his color stylist Walt Peregoy, had designed using the Xerox technique. And upon reevaluating it many years later in 1991, Roger Ebert lamented that “By the time the film was made, the golden days of full animation were already past. It was simply too expensive to animate every frame by hand, as Disney did in earlier days, and computer assistance was still in the future. In a film like ‘101 Dalmatians,’ you can see certain compromises, as when the foreground figures are fully animated but the backgrounds look static and sometimes one-dimensional.”

Besides showcasing gorgeous background drawings (the likes of which had not been seen onscreen before), I think the genius of One Hundred and one Dalmatians’s aesthetic lies in this middle-ground between traditional methods and modern techniques. The stiller, more painted-looking backgrounds, plus the wobbly lines in the buildings and trees, make the film look somewhat antique… while also giving way to the most modern and impressive feat thus far in animation: the extravaganza of a hundred spotted dogs running individually across the screen.

as with works of art in a museum, the point of the film’s aesthetic is to capture the movement within still art, rather than expect movement only from rapidly-displayed sequential images.The backgrounds of One Hundred and one Dalmatians knowingly provide a break from the kinetic spectacles of modern entertainment, allowing a nod to an older, more traditional form of art: painting, itself. There are long establishing shots and pans that deliberately dwell on the stiller landscapes and city views; as with works of art in a museum, the point of the film’s aesthetic is to capture the movement within still art, rather than expect movement only from rapidly-displayed sequential images.

Personally, I haven’t seen more evocative background images in any animated film than One Hundred and One Dalmatians. The look captures so perfectly a kind of wistful Bohemiana of late 50s London. I’ve never wanted to walk around in a film so much as this.

Constantly, One Hundred and one Dalmatians represents a give-and-take between stillness and chaos—placid walks in the park and then hectic meet-cutes, lonely snow-capped hills that are suddenly disrupted by the desperate strides of running dogs. Even the Barking Chain is bustling in London and then thinned out when it gets to the country—with one dog passing the word to another dog across miles of desolate nature.

In this simple way, One Hundred and one Dalmatians captures the interplay of contemporary innovation and traditional approaches that so dramatically pervades this moment in mid-century history. And when the film ends, on a complicated scene of one hundred and one dogs and three humans in the Radcliffe’s parlour, it chooses both at the same time: over an exhausting shot, pulling out over this many individuated dogs moving separately (a moment that reinforces the practical and manual side of the film), it also ends on a note of imagination and near-implausibility, the promise to care for five-score dogs. A promise which will cause the Radcliffes and the Pongos to leave London behind and move to the country… whose stillness and space can accommodate, at the very least, that many dogs moving around.