One and I had a novel, two and I had a sequel, three and I finally felt I could say I had a series. So the occasion of my third Charlie Waldo book, Pay or Play, has me thinking about the works that shaped my own instincts about how to build and sustain a run.

Truth be told, I was a child of television, so that’s where my biggest influences lie. I’d had a long career writing TV and movies, too, before I became a serious reader of crime fiction.

I was also a child of the 70s, the celebrated decade of Columbo and The Rockford Files. But for me, the 80s were the true Golden Age of TV crime, the decade that changed what and how we watched and laid the foundation for all the other masterpieces which followed. Somehow, though, many of that decade’s high points have become criminally underappreciated. So I’d like to draw your attention to half a dozen unsung highlights of that Golden Age, and sing about them a bit.

THE EQUALIZER (1985-89)

In 1985, the year of The Equalizer’s premiere, New York City was home to three times the murders of the city we know now, and five times the robberies. The chilling title sequence captures that New York so well, you think even the Chrysler Building is about to mug you. (N.B., this was also the year I moved there.) It’s The Prisoner meets Death Wish: Edward Woodward plays an operative of an unnamed U.S. intelligence agency who angers his overlords by retiring without permission, then runs an ad in the paper (“ODDS AGAINST YOU? NEED HELP? CALL THE EQUALIZER”), and becomes pro bono protector of the city’s desperate, through manipulation or violence as the situation demands. His paunch and gray hair belie his Bondian talents; his bespoke wardrobe and Jaguar belie his tortured conscience. The best scenes of this elegant series (created by Michael Sloan and Richard Lindheim, originally exec produced by James McAdams) feature Robert Lansing as his former boss and frenemy, elliptical negotiations burdened with the weight of old and complicated debts. Nobody upstages Woodward, though, except perhaps Stewart Copeland of the Police (Sting’s Police, that is, not the NYPD), who provides the unforgettable score, with hairpin turns from dissonant to melodic, from paranoiac to heroic.

CRIME STORY (1986-1988)

Exec producer Michael Mann had a bigger impact on the 80s with Miami Vice—I was working in advertising when it came out, and watched first-hand as it instantly defined the decade’s style. But it’s his little-remembered next show (created by Chuck Adamson and Gustave Reininger) that’s had the enduring influence. Mann trades Miami’s pastels for the grays of Chicago in the early 60s, and the pretty boys for Dennis Farina, a former real-life cop in the role that made his new career: a hard-boiled lieutenant playing it rough in the pre-Miranda days and obsessed with Anthony Denison’s sociopathic mobster on the rise. (Mann perfected this two-man dance a decade later with De Niro and Pacino in Heat.) There’s style galore—tailfins and pompadours and a soundtrack full of pre-Beatles gems—but what made Crime Story a game-changer was that it treated that cat and mouse game as one long plot, with a recap at the beginning and a “TO BE CONTINUED…” title card at the end. You had to plan your week around it, or figure out how to set your VCR, if you had one. That met a lot of resentment, and the show only lasted two seasons. But it changed the game.

WISEGUY (1987-1990)

And this was the first series to stand on its shoulders. Exec producer Steven J. Cannell and his co-creator, Frank Lupo, built it to run in sub-seasons, two or three story arcs of five to ten episodes each. Cannell’s prolific career always intrigued me, swinging between the sublime (the man co-created The freaking Rockford Files) and the ridiculous (he co-created The freaking A-Team). Count Wiseguy with the sublime, with stories that keep twisting and dialogue that shimmers. Ken Wahl is a Brooklyn street kid who goes undercover for the FBI, where he suffers the emotional torture of deep secrets and complex loyalties under the supervision of FBI man Jonathan Banks, who’s just as flat-eyed, world-weary and mesmerizing as he’d be two decades later in Breaking Bad. Wiseguy’s lasting contribution to the form was the elevation of its vivid antagonists to near-equal status with the series lead. As a mob boss in the first arc, it’s an electric Ray Sharkey (whose actual life story is an 80s cautionary tale); in the second, it’s no less than Kevin Spacey in his breakthrough role, as a drug-addicted and unstable arms-and-everything-else dealer. And, in an arc on mob influence in the garment district, could I interest you in Stanley Tucci and Ron Silver and Jerry Lewis?

CAGNEY & LACEY (1982-88)

More traditional than the aforementioned in form and style, this cop show’s aged less gracefully, but its groundbreaking content makes it every bit as notable. Back when women on the force were still a novelty, exec producer Barney Rosenzweig and co-creators Barbara Avedon and Barbara Corday paired two as leads, and didn’t stop there. The scripts steer into every cultural storm of the era, tackling abortion, molestation, breast cancer and alcoholism, to name a few. (In this, its primogenitor was the newspaper show Lou Grant, also too little remembered.) From the jump, it’s Tyne Daly as the married working mom, but casting her single and more career-minded partner was more fitful and a reflection of the challenges women faced at the time. Loretta Swit, who starred in the original C&L TV movie, was committed to M*A*S*H and replaced by Meg Foster for the first six episodes, at which point CBS deemed the combination of Daly and Foster too masculine and almost canceled the show. Instead, crazy as it sounds now, they brought in a third Christine Cagney, Sharon Gless, whose toughness came with softer edges and a smile that could melt tungsten. Ratings gold never followed, but a devoted fan base kept it on the network schedule, and either Daly or Gless took home the Best Actress Emmy in each of their six years together.

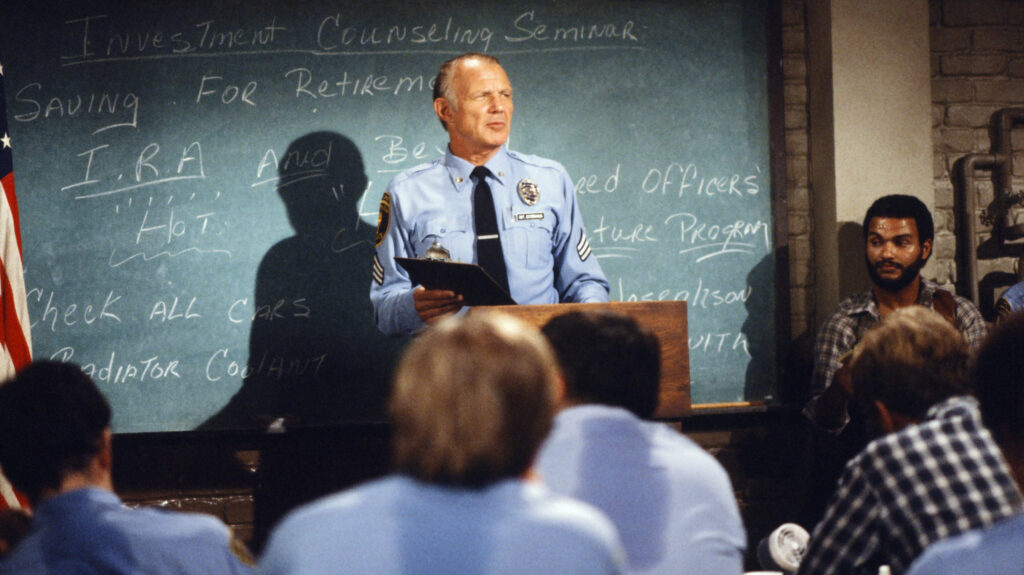

BARNEY MILLER (1975-82)

It’s this old showrunner’s all-time favorite sitcom. The set was shabby and gray and so were the actors, for that matter, an all-male but ethnically diverse ensemble of schleppy veterans cast for comedy over comeliness. (Think of it as the anti-Friends.) Hal Linden, the titular captain in the middle, was moral core and father figure. Breakout star Abe Vigoda could draw big laughs by deflating half an inch; Jack Soo could do even more with even less. The same crime-infested city that The Equalizer mined for thrills, Barney Miller mined for laughs, via a parade of wild-eyed victims, philosopher-thieves, fleeced tourists, feuding neighbors, pill-poppers and perverts and prostitutes, and, most of all, madmen of every stripe. (Rare was the episode in which Barney wasn’t telling one of his detectives to “call Bellview.”) Producer Danny Arnold (also co-creator, with Theodore J. Flicker) delivered the driest wit in the history of television, its comedic sensibility animated by a combination of fatalism and humanism that I now recognize as classically Jewish. Unlike most of the legendary sitcoms, it boasts no famous single episode, but—despite Arnold’s unequaled notoriety for cranking out scripts at the last minute—somehow ran eight seasons without making a dud, something I don’t think any other multi-cam can claim. Unless you’ve worked the relentless treadmill of network comedy, you can’t imagine what an achievement that is.

HILL STREET BLUES (1981-87)

Can you call a series with 26 Emmy Awards and 98 nominations unsung? Yes, because Hill Street Blues wasn’t just superlative television: it changed the medium like Babe Ruth changed baseball. Without Hill Street’s sprawl, there’s no The Wire. Without the way it punctuated comedy with sudden violence, there’s no Sopranos or Breaking Bad. Creators Steven Bochco and Michael Kozoll (who shared exec producer credit for the first season, Bochco maintaining it solo through season five) packed more into 50 small-screen minutes than anyone had ever dared. There are over a dozen lead characters featured in the opening credits, plus scores more recurring. The shots are often handheld, dirty, and jump storylines without pausing for a breath, while clever snippets of off-camera dialogue pepper the soundtrack. Single-episode stories overlap multi-episode arcs and others that last a season or more. No TV show had ever demanded so much attention, and no show had ever rewarded it. The conscious Barney Miller influence is evident in the ratty set and in the nervy blend of humor and darkness (both shows feature tragicomic suicides early in their first seasons), but, most important, in the precinct captain at its center. Here it’s Daniel J. Travanti as Frank Furillo, a man of uncommon decency, compassion and honor—standards his charges struggle to meet on the streets of their chaotic, unnamed city. Travanti (like his character, a former alcoholic) plays him with a stillness that teases the viewer into thinking you know what he’s thinking, only to confound expectations and reveal unforeseen dimension. When Furillo’s choices lead to the murder of an undercover cop, one of his most loyal detectives fumes, “His death is on your head!” Furillo blinks surprise, but he’s not, as it seems, taken aback by the bitter denunciation. Instead, his answer, “They all are, Mick,” bleeds with Furillo’s surprise that his detective doesn’t realize the weight he constantly carries. And then it’s the viewer’s turn to blink surprise, because we didn’t, quite, either. God, how I loved this show.

***