When I was twelve years old, I stumbled upon two authors in the adult section of the library that changed my life and directed my reading tastes for years to come. For years my parents would only let me check out as many books as I could carry myself, only to have to turn around three days later and take me back to the library because I’d read them all. Usually twice. Mysteries and suspense were early favorites—The Bobbsey Twins, Trixie Belden, the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew, Cherry Ames. I think I read The Westing Game by Ellen Raskin twenty times in my fifth-grade year.

So I was all set to fall into the worlds of Victoria Holt and Agatha Christie. One of the very best things about these discoveries was the prolific output of both writers—entire shelves with story after story just waiting for me to read them. (I still get that thrill when I find an author with a lengthy backlist!)

What could possibly connect these two genres beyond the excitement of an almost-teenage girl with dozens of new books to read? Let’s see: castles and drawing rooms, vicarages and afternoon tea, horses and candlelight, titles and vintage fashion and, prominently in both, secrets.

Both gothic novels and locked-room mysteries…are built upon physical and emotional isolation.As I’ve gotten older and my reading has become professional as well as personal, I’ve come to recognize another trait they have in common: isolation. Whether it’s Jane Eyre living among strangers at Thornfield Hall or a murder committed on a snowed-in train, both gothic novels and locked-room mysteries (I use that term generously to refer to any mystery where the suspect list is confined to a small, closed society) are built upon physical and emotional isolation. For whatever psychological/subconscious reasons, stories of secrets hidden in isolated settings and communities have always resonated with me. (It is perhaps interesting that I live in a house with almost no blinds or curtains, allowing anyone coming down our nearly-hidden driveway to see everything…)

But in my fiction, at least, I attempted to create that claustrophobic, lonely atmosphere in The Darkling Bride. Almost my first reference to Deeprath Castle in the novel has little to do with its structure and everything to do with its aura: “The castle knew her own, and jealously kept their secrets.”

With that in mind, here’s a reading list that specialize in that delicious, terrible sense of isolation and the secrets it magnifies. Enjoy!

Victoria Holt, The Mistress of Mellyn

The very first Holt book I ever read finds Martha Leigh travelling to Mount Mellyn on the Cornish coast. As she approaches the bridge across the Tamar river, Martha dwells on this crossing, after which “I should have left England behind me and entered the Duchy of Cornwall”—a very specific note of isolation struck in the first pages.

In best gothic tradition, Martha goes on: “I was not a fanciful woman at this time—perhaps I changed later, but then a stay in a house like Mount Mellyn was enough to make the most practical of people fanciful.” Especially when the isolated house on an isolated coast is peopled by a brooding and arrogant widower, an orphaned girl who doesn’t speak, and whispers about the death of the previous mistress.

Agatha Christie, And Then There Were None

There could hardly be a better example of a locked-room mystery then Christie’s famous story set on Indian Island. Ten strangers arrive, realize they’ve been brought there under false pretenses, are each accused by a recorded voice of having committed a crime . . . and then the first of them drops dead. One after another they are murdered, while a raging storm isolates them from the mainland. It doesn’t get more gothic and claustrophobic than that. (The 2015 BBC adaptation brilliantly captures the atmosphere of rising dread. I highly recommend it—and not just because Aidan Turner stars.)

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw

James’s novella is a masterpiece of ambiguity. Does the unnamed governess see evil ghosts, or is she going mad? Were the children terrorized by their former caregivers—or by their current one? Whichever it is, much of the effect of the story rests upon the fact that, when offered employment, the gentleman who engages her gives one overriding condition: “That she should never trouble him, but never, never: neither appeal nor complain nor write about anything . . . take the whole thing over and let him alone.” Whatever the reason for that rule, the effect is to leave the governess entirely to her own judgment just when she most doubts the evidence of her senses.

Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night

One of the great writers of the Golden Age of mysteries, this best of Sayers’ work does not have even a single dead body. Writer Harriet Vane has returned to 1930’s Oxford to help discover the poison pen who is leaving venomous letters and engaging in increasingly dangerous tricks. The atmosphere depends upon the almost cloistered nature of the female academics, and philosophical questions about a woman’s ability to be loyal to both her work and her relationships become increasingly bitter as everyone begins to suspect everyone else.

As Harriet tells Peter Wimsey: “I’m beginning to feel that almost any one of them might be capable of it.” To which he replies: “That . . . is where your fears are distorting your judgment.” Which sums up, as well as any one line could, the nature of both gothic and locked-room terror. If it could be anyone, then how can I trust even myself?

Susan Hill, The Woman in Black

Also a fine mystery writer, Hill’s story of Arthur Kipps (a slight oddity, a man taking the traditional gothic place of an innocent young woman) and his stay at Eel Marsh House is set up by the lawyer’s total and complete isolation once he’s there: “I realized that this must be the Nine Lives Causeway [Note: because that’s not a terrifying name]. . . and saw how, when the tide came in, it would quickly be quite submerged and untraceable.”

Not only is the house unreachable for most of the time, but Kipps is utterly alone as he goes about his work of clearing up the dead client’s affairs. So how can he be sure that the rocking chair is moving without anyone in it? Or that he really hears a pony trap in the fog, followed by a child’s scream? And surely the woman in black he sees is nothing more than his fevered imagination, unchecked by any human company.

Tana French, The Likeness

The second book in French’s Dublin Murder Squad series opens with Detective Cassie Maddox confronting the body of her doppelganger. When it turns out the dead girl was using an alias that Cassie herself created while undercover, she agrees to assume the life of Lexie Madison to try and catch her killer. That means living at Whitethorn House, an aging Georgian manor, with four friends who may or may not have killed Lexie themselves.

The moment she steps into Whitethorn House, Cassie thinks: “I’ve been here before. It zinged straight through me, straightened my spine like a crash of cymbals.” And the longer Cassie is removed from her own name and life, the greater the danger she’ll forget who she is and why she’s there. This is a classic mystery where finding out who did it doesn’t matter half as much as why, and where the cost of justice may be too high to pay.

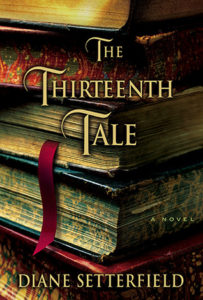

Diane Setterfield, The Thirteenth Tale

Margaret Lea is a quiet bookseller who is startled to be summoned by the famous Vida Winter to write her biography. After many decades of lying fantastically about her origins, Vida wants to dictate the truth before she dies. She allows no questions while she tells her story, until Margaret begins to feel she herself is living in the past at Angelfield with disturbing twins sisters and an actual madwoman in the attic. The more Vida talks, the more mysterious her past grows. And Margaret is getting no closer to finding the famous thirteenth tale from the writer’s first story collection. Was it ever actually written? And if found, what secrets might still be uncovered?