My reading list lately has been a mix of some new authors I’ve never read, as well as some classics that I’ve been re-reading to study a couple great authors’ crafts. Like a lot of writers, while I’m working on a manuscript, I get anxious about reading too many books in the fear that I might be unduly influenced by a great writer’s style. And so, in that ‘in-between time,’ while my editor is reading my latest draft, I binge-read, suddenly willing and wanting to be influenced.

And based on the particular mix of books lately, I’ve begun thinking about the subject of violence. But not just any violence. Specifically, how we writers tend to take our main characters and allow them (once a book) to get burned… or outwitted… or cornered… and then clobbered.

I attend a weekly writing workshop, and the author who runs it constantly reminds me that my detective must be the smartest guy in the room. “P.T. has to have a smarter way to solve that problem,” Jerrilyn Farmer says to me when my detective doesn’t find the most novel way out of a pickle. And recently I’ve been thinking that it’s this ‘smartest guy in the room’ philosophy that causes two things to happen: One, readers fall in love with a character; and two, readers look the other way and don’t notice all that character’s flaws, personality defects, and hang-ups. And yet at the same time, it’s those very things that eventually lead that protagonist to get the snot beaten out of him.

In T. Jefferson Parker’s The Last Good Guy, private investigator Roland Ford is approached by a client whose daughter has gone missing. And even though he doesn’t trust the woman from their first meeting, P.I. Ford steals onto private land in the desert east of San Diego and puts himself in harm’s way. In doing so, he’s surrounded by a team of men on ATV’s. Ford has a little bit of a boxing background, and that helps him take down the first two men. But slowly he is overwhelmed, surrounded, and begins to get beaten badly. “You cannot win a fight against six determined men wearing helmets,” Ford narrates. And soon the private investigator is fading from consciousness. “Blood in my eyes and the crack of blows. I couldn’t see what was coming. Rising whoops and snarls.” The men then drag Ford’s body with their ATVs, “the grumble of engines pulling me. Can’t be real. Close your eyes, and it will go away.”

In James Lee Burke’s The Neon Rain, the character of Dave Robicheaux gets similarly taken down. Robicheaux has found a woman’s body floating in a swamp. And he will place himself in front of dangerous mobsters, drug smugglers and other cops, all to figure out what happened to this woman, who was a prostitute. At a specific point in the book, the protagonist finds himself surrounded by three men in a bathroom, intent on waterboarding him, years before we knew the term “waterboarding.” “Erik grabbed my hair and slammed my head against the side of the tub. I kicked at all of them blindly, but my feet struck at empty air.” In a moment, Robicheaux feels life slipping away and says, “I knew that all my past fears of being shot-gunned by a psychotic, of being shanked by an addict, of stepping on a mine in Vietnam, were just the foolish preoccupations of youth; that my real nemesis had always been a redneck lover who would hold me upside against his chest while my soul slipped through a green watery porcelain hole in the earth.”

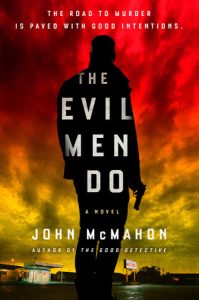

Lastly, in my own book, The Evil Men Do, Detective P.T. Marsh finds himself surrounded by a group of self-described peckerwood farmers, one in particular hitting him with a baseball bat. He wrestles the bat away, but instead of escaping with the bruises he’s got, P.T. wants a fight. “My face was bleeding badly,” P.T. narrates. “But I got up and waved the bat around, daring the men to come at me.” When the two men take off, P.T. smiles, blood across his teeth. “I was torn up a bit,” he says. “And my service weapon was gone, but something wild inside me was laughing, and I felt crazier than a shithouse rat. Let the forces come at me. Tonight I get to the truth… and I don’t care if it kills me.”

As a reader of several crime series myself, it’s easy to see the plot reasons for these beatings. P.I. Ford must sneak onto that property and take a beating to collect intel. And in doing so, he is more sure than ever that something nefarious is afoot on that land. Is it military? Is it a conspiracy related to politics or religion? His beating puts him one step further to the truth. In The Neon Rain, Dave Robicheaux has to go through his beating to meet a woman named Annie and to understand why he’s been targeted himself. And P.T. Marsh sends those angry farmers on a fool’s errand that, in turn, may cost them their lives, but helps him survive.

But below the surface of the plot moves, there is always something deeper. Often it is a revelation of character and shows us a psychological scar. In T. Jefferson Parker’s book, the P.I.’s client is a proxy for the protagonist’s lost wife. And so the P.I. is effectively putting himself in a dangerous high-risk situation to demonstrate love for his lost wife.

Increasingly I’ve heard writers refer to the words “magic trick” in terms of some device we use to get readers to look away, while we show a bad guy or introduce a dangerous element. But maybe the greatest magic trick we do is not having our audience stare directly into the eyes of the characters they love most. Or maybe they are staring, but we’ve made our heroes so damn lovable that—like family members—you forgive all their faults.

And that’s what’s most interesting to me about the power of a good beating. See, we root for these heroes—whether it’s Dave Robicheaux or P.T. Marsh or Roland Ford because as readers, we love the smartest guy (or girl) in the room. And we love them because they find a way out—without fail. Or they see something that others don’t. Or they go to great lengths… never quitting… and never stopping until they find the truth.

But in loving them for that, we look away from other traits. Like their arrogance. Like the fact they are repeating mistakes from their past. Or are selfish. Or unnecessarily stubborn. Sometimes even mean-spirited.

In the throes of those beatings, we readers shake our heads at our heroes, but forgive them, in the same way we do a good friend. And in that way, we take them in, in the same way we do family or friends or damaged animals—unconditionally—the good with the bad.

…readers recognize themselves in the most frail parts of their heroes. The parts that can’t help but make mistakes.

I recently spoke to a group of middle school kids in the Savannah school system about how writers create characters. I advised them to create heroes that are imperfect because imperfect humans make mistakes and that will create real and natural conflict. But maybe more importantly, readers recognize themselves in the most frail parts of their heroes. The parts that can’t help but make mistakes. The parts that put those heroes (again and again) into dangerous circumstances.

I think the true power of a good beating is that the reader suffers alongside these characters. And I think as authors it allows us this honest moment where we reveal those bad traits that we may have hidden at other times. We do this at a time when we can clearly show what got our protagonists into this mess without the reader holding them responsible. Because the second part of the magic trick is the reveal. And in this moment, we hang out the laundry for all to see. We show off every one of those negatives, but do it when readers feel most connected to their heroes. Right when they’re in jeopardy and are at their most vulnerable. And that makes them feel like family even more.