Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stretched onto the bed, curling ever so slightly to his side. He looked crisp yet casual in his suit trousers and shirtsleeves. If he worried the FBI had bugged his room here at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, as it had in so many hotels across America, he didn’t show it. Leisurely, he threw his arm behind his head and stared into the camera. It was rare for King, viewed by some in the media as tense and aloof, to be at such ease with a newsman.

But this was different.

The man holding the camera was Ernest Withers, a slightly chubby, extremely personable freelancer known to some civil rights insiders as Ernie, the down-home Beale Street studio photographer with press credentials, a wispy mustache, and a wide smile few could resist.

Yet to the FBI special agent who slipped Ernie cash, the photographer was something far different—a confidential “racial” informant smuggling precious nuggets of intel from behind the color barrier separating black and white America. By this time, 1966, Withers had been working for the Bureau for as many as eight years. He became so valuable that in 1967 his handlers began protecting his identity in internal reports with a code number, ME 338-R.

What, if anything, Withers told the FBI on this warm June day in 1966 isn’t known. Yet records show the newsman began relaying dozens of tips on King and his staff two years later as Memphis’s volatile sanitation strike erupted. Troubled that the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was overrun with Communists and dangerous militants, King’s old adversary J. Edgar Hoover oversaw what would become the latest in a series of FBI campaigns to disrupt and discredit the thirty-nine-year-old Nobel laureate.

In Memphis, Withers played a critical role. Starting two weeks before King’s April 4, 1968, assassination and continuing for another year and a half as SCLC aides repeatedly returned to Memphis, he shot photos and relayed intelligence that painted a troubling portrait: one of King’s top aides appeared to harbor sympathies for a virulent strain of Black Power, he said; others on King’s executive staff exhibited an intense militancy. King, too, was meeting with Black Power militants. Collectively, the details fueled deepening skepticism within an already hostile FBI as to whether the civil rights leader intended to keep his movement nonviolent.

“I’m not going to place the blame here on Ernie Withers,” King’s longtime friend Rev. James Lawson would say years later after Withers died at age eighty-five, after his secret finally came out. The heralded photographer had been the FBI’s go-to man inside the movement in Memphis for more than a decade.

Collectively, the details fueled deepening skepticism within an already hostile FBI as to whether the civil rights leader intended to keep his movement nonviolent.Lawson found it hard to accept. A chief architect of the sit-in and Freedom Rider movements, he’d worked with Withers for years. What he didn’t know was that he, too, became the focus of dozens of tips Withers passed to the FBI: one involving the militant pastor’s plans to coach young men in ways to dodge the draft, another on a trip he’d planned to communist Czechoslovakia—even a sermon he preached that seemed to question the virgin birth of Christ.

Yet even now, his hair snow-white and his voice weary, the aging activist-pastor struggled. Ernie must have been induced. Manipulated. After all, he was vulnerable. With eight children to feed he was always in need of extra cash. No, he couldn’t blame Ernie. Besides, things were different back then. They trusted the FBI. They had no idea just how far Hoover would go to destroy King—how hard the FBI had worked to derail the movement.

“In the age in which we lived we were not as aware,” Lawson argued.

***

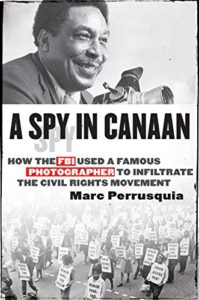

This book tells the story of the double life of Ernest Withers and how this closely guarded government secret finally came to light. Against all odds, my financially struggling newspaper overcame powerful laws that allow the FBI to shield the identity of informants—even to lie about them— long after their work is over, even after they die. The story of this on-again, off-again investigation starts in 1997, when a retired FBI agent first told me about Withers. Following years of detective work and a costly lawsuit that forced the FBI to release a mother lode of classified records between 2013 and 2015, we finally broke the news that the beloved civil rights photographer had secretly spied on the movement for as many as eighteen years—the very movement he helped propel with his iconic black-and-white photographs.

It was a radical rewrite of history.

Withers is a legend in Memphis. A street and a building are named for him. He’s honored by a brass “Blues Note,” the local equivalent of the Hollywood Star, embedded in the sidewalk along world-famous Beale Street. Though many today might not recall the “Original Civil Rights Photographer,” his work is buried deep in our collective conscious.

The picture of Dr. King riding one of the first integrated buses in Montgomery? Withers shot it. The haunting photo of Emmett Till’s wispy great-uncle Moses Wright pointing an accusing finger at the teen’s killers? That’s his, too.

When I first started sizing up this story, digging through boxes of old records and yellowed newspaper clippings, it was clear Withers’s life was extraordinary, even without the FBI component. He navigated an astonishing, almost surreal, range of highs and lows: a friend to famous bluesmen like B.B. King and Howlin’ Wolf; a policeman who served as one of Memphis’s early black officers, only to be kicked off the force for bootlegging; a chronicler of Negro Leagues baseball who knew the legends Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, and Roy Campanella; a dinner guest at Jimmy Carter’s White House. As a witness to the aftermath of Dr. King’s 1968 assassination, he used his incredible access to view King’s body in a funeral parlor morgue room, and even held a piece of the fallen civil rights leader’s skull in his hands.

Withers’s incredible saga is told in this book from a reporter’s perspective—a narrative of discovery. It recounts, piece by piece, the many unfolding sides of this complicated and historically significant man’s life. For all he did, it was his role as a hard-charging freelance photographer for America’s black press—newspapers serving a largely African American readership—where Withers shone. He shot timeless photos of the Little Rock Nine anxiously walking to their first day of classes at military-occupied Central High; of striking garbagemen carrying placards reading “I AM A MAN” as they fought for dignity and a living wage in Memphis; of the mournful funeral of Medgar Evers, the Mississippi NAACP field secretary ambushed under his carport as he came home from work to his wife and children.

Withers’s work earned him the trust of the movement’s leaders, people like King, Evers, and Lawson, and many others whose activism brought them to Memphis—Ralph Abernathy, James Forman, Fannie Lou Hamer, Andrew Young, James Bevel, Virgie Hortenstine, and Dick Gregory among them. But none knew his secret.

***

His FBI work was prolific. Between 1958 and 1976, Withers produced a staccato of photographic prints, negatives, and oral intelligence. His collaboration contributed more than 1,400 unique photos and written reports to the files of the FBI’s massive domestic intelligence vault, a history detailed for the first time in this book.

In return, he was paid $20,088—an amount roughly equal to $150,000 in 2018. It wasn’t huge. But it was considerable. The tight-fisted FBI paid most of its informants nothing. Though Withers was among as many as 7,400 so-called ghetto informants operating nationwide for the surveillance state of the late 1960s, he was in a select group. Among scores of Memphis informers, he was one of just five getting paid in 1968 to report on the racial strife there.

His first known contact with the FBI as an informer came in 1958 in Little Rock, where he helped identify renowned activist James Forman, then an obscure Chicago schoolteacher who’d begun turning up at civil rights skirmishes and was put under investigation as a suspected Communist. A single, surviving report tells the story. Withers came into the Little Rock field office one day with legendary Jet magazine reporter Simeon Booker, who endured his own controversy as an alleged informer. These were simpler days. By the mid- to late-1960s, many black journalists were openly defying the FBI’s overtures for information. But in the innocence of the movement’s early days, journalists like Booker looked to the FBI for protection. The details of Withers’s early cooperation remain sketchy. But one thing is clear: he got in deep.

His relationship with the FBI blossomed in 1961. He began working with special agent William H. Lawrence, the resolute William F. Buckley– styled conservative who ran the Bureau’s domestic intelligence unit in Memphis for over two decades and eviscerated the Communist Party there. The two men shared much in common. Both grew up Baptist. Both had law enforcement backgrounds. Both loved music. A jazz enthusiast, the savvy Lawrence knew how to manipulate mutual interests—how to connect with potential informers. He knew, too, of Withers’s scandalous career as a cop. It hindered the photographer at first. But Lawrence knew he was onto something good. Citing Withers’s “many contacts in the racial field,” the agent found ways to steer around skeptical supervisors and advance Withers from a lesser, “confidential source” into the ranks of directed informants.

He was valuable on several fronts. First, he helped the FBI assemble dossiers, for which identification photos were critical centerpieces. The FBI wanted clear, up-to-date images as it cataloged the movement, building a virtual library of secret files on civil rights workers, peace activists, and other “subversives.” Group photos Withers shot often were cut up at FBI offices into face shots and placed in individual files. Copies were shipped to other FBI field offices or shared with local police. Often, the agency bought photos Withers had shot at events he’d covered on his own as a newsman. But increasingly, starting in the summer of 1961, Lawrence dispatched Withers to shoot in the field.

Demand for pictures grew as Northern “agitators” began pouring into the area to assist impoverished sharecroppers kicked off their land for trying to vote and as a radical sect known as the Nation of Islam began recruiting on Beale Street. Often, the photographer received explicit advance instructions. In April 1966, for example, Withers was directed to photograph a march against the Vietnam War while “posing as a newsman.” Following Lawrence’s directives to “get good facial views of the participants,” Withers delivered eighty 8-by-10 identification photos to the FBI’s Memphis office.

The relationship centered on photos. Yet, from the start, the FBI paid him for oral intel, too. In July 1961, for example, Lawrence paid the photographer $15 (about $120 today) to tap his contacts for information on a busload of Freedom Riders headed to Memphis. In time, Withers began operating like a listening post—acting as the FBI’s eyes and ears in the black community. He and Lawrence met in periodic intervals. In lean times, this might happen every few weeks or so. During the chaos of the 1968 sanitation strike it became virtually a daily routine. Driving these investigations were Hoover’s obsessions with black America, Cold War fears of insurrection, and, later, the riots and unrest that shook urban America in the mid- to late-1960s. These were volatile times—the greatest internal crisis since the Civil War.

Overtly, the FBI aimed to protect the country’s internal security—to prevent violence and preserve civil order. Withers proved effective. While informing on the Invaders, a homegrown Black Power group, he aided in the arrests of two militants accused of murder and another of assault. He reported others advocating the use of incendiary Molotov cocktails. But he also helped the all-white FBI understand that not every youth sporting a faddish dashiki and an Afro hairstyle was a revolutionary.

He aided in the arrests of two militants accused of murder and another of assault…But he also helped the all-white FBI understand that not every youth sporting a faddish dashiki and an Afro hairstyle was a revolutionary.Yet just as congressional investigations uncovered wide abuse nationally in the FBI’s domestic surveillance, the Withers files document repeated disregard for the rights of law-abiding citizens simply exercising rights to free speech, dissent, and political affiliation. Forget what you think you know about an informant. The intelligence informants of the 1960s surveillance state weren’t criminal informants pursuing narrow threads of information to build a specific case for prosecution. They captured broad swaths of personal and political data that jeopardized careers and livelihoods. An enthusiastic gossip, Withers thrived in the role. He routinely relayed backbiting rumors and potentially damaging private details: A civil rights worker in Fayette County had contracted a venereal disease, he said. King aide James Bevel had “weird sexual hangups.” Memphis NAACP leader Maxine Smith had left her husband, Vasco, and was living in a Midtown apartment.

Even soul singer Isaac Hayes was implicated. Months before he released Hot Buttered Soul to diverse acclaim, Hayes mirrored the rhetoric of the day, giving a fiery Black Power speech—details Withers relayed to the FBI despite the singer’s admonitions to the all-black audience against repeating his comments.

When King’s SCLC launched a chapter in Memphis in 1969, Withers, the consummate insider, gained a seat on its board of directors, funneling inside accounts of meetings, financial information, and names of individuals he viewed with suspicion to special agent Lawrence. As a newsman, he could ask for personal information without a hint of suspicion: names, addresses, occupations, phone numbers. Phone numbers made for especially pernicious inquiries. Lawrence used them to conduct warrantless searches of a subject’s toll charges. Over time, as the mainstream movement collapsed, the FBI revised Withers’s code number, shifting him from racial informant ME 338-R to extremist informant ME 338-E, who reported on fringe groups like the Black Panthers, which had formed a small Memphis organization, and a resurgent Communist Party.

“Withers is no innocent,” said retired Marquette University professor Athan Theoharis, an authority on civil rights–era FBI surveillance who reviewed many of the Withers records. “He knew what he was doing.”

***

Did Withers betray the movement? It’s a question with many answers—all of them subjective. To his faithful circle of family and supporters, who have zealously defended his legacy, the answer is an emphatic no. “In the battle between Hoover’s F.B.I. and King’s movement—between those who tried to suppress our rights and those who fought against them—nothing in these files shakes my belief about which side Ernest Withers was on,” writer Daniel Wolff, the photographer’s friend and collaborator on two books, wrote in an early defense.

Did Withers betray the movement? It’s a question with many answers—all of them subjective.But the central question about Withers’s FBI collaboration isn’t whether he betrayed the movement; it’s something far more vexing, involving personal relationships and friendships like the one Withers shared with Coby Smith, a young activist in 1967 who cofounded the Invaders with Charles Cabbage, an intellectual-turned-petty-street-criminal who viewed the older photographer as a “dear friend.” Between 1966 and 1969, Withers passed dozens of photos of the two men to Lawrence. He relayed intel that the agent included in scores of written reports. That intel led to both young men’s placement on the Security Index, the FBI’s list of “dangerous” subversives to be rounded up in time of national crisis.

“He betrayed my friendship,” said Smith, who distanced himself from the Invaders when its rhetoric grew increasingly violent, earning a doctoral degree in education. Still, the stigma stuck and it took him years to find work in Memphis. “He was our family photographer. And, you know, he took the yearbook pictures. He took the prom pictures. He took the parade pictures.”

Withers took Kathy Roop Hunninen’s wedding photos—and secretly funneled scores of pictures and bits of intel about her to the FBI. A former war protestor and civil rights activist, she suffered years of trauma and depression after she lost her federal job in 1986 when reports surfaced of the FBI’s long-running investigation of her as a suspected Communist in Memphis in the late 1960s and early ’70s. “This man has ruined my life. He has ruined my life,” Hunninen said. “Betrayal? Betrayal isn’t even the word. I have been scarred for life.”

***

None of this can change the good he did. Though he remains obscure to many, arguably Withers is one of the great photographers of the twentieth century. He shot as many as a million photos over sixty years documenting black life in the South. If he’d only shot three he would still secure a spot in the pantheon of immortal shutterbugs: King on that integrated bus. Till’s great-uncle pointing that accusing finger. And his haunting photo of Memphis’s striking garbagemen dressed in their Sunday best, carrying those “I AM A MAN” signs as they protested for the most basic of rights—to make a living wage; to work with dignity; to be treated as human beings. Each was pivotal and consequential.

“I view him as a guy who ran significant risk to photograph and record our history,” said Andrew Young, King’s close aide who was later elected mayor of Atlanta and appointed by President Carter as ambassador to the United Nations. “He always showed up. And that was important to us.

Because that helped us get our story out.”

Whatever motivated Withers to collaborate with the FBI—money, patriotism, or his long ambition to be a cop—his story is instructive. It opens a window into a dark, injurious period. We know the macro, the sweeping, big picture of our government’s spying on Americans. But we know so little of the micro, the intricacies of how authorities induced or compelled individuals to inform on their fellow citizens. Even now, fifty years later, restrictive laws make those types of details elusive. It is not my intention to erode the memory of Withers, nor to reduce him. He will forever remain a Memphis hero. Instead, my hope is that the story of Ernest Columbus Withers will help fill in many of those gaps that still exist in the twin histories of civil rights and government surveillance.

__________________________________

From A Spy in Canaan: How the FBI Used a Famous Photographer to Infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement, by Marc Perrusquia. Courtesy Melville House. Copyright © 2018, Marc Perrusquia.