We all think of Sherlock Holmes as a rational thinker, a scientist, a man who uses remarkable powers of inference, deduction and observation to extract the truth from a tangled mass of facts. Holmes brings the rigor of scientific thinking to crime solving—a new idea in the nineteenth century, but now standard practice.

Of course Holmes is every bit as much as artist as he is a scientist.

But artists create. What, exactly does Holmes create? You won’t find daubs of cerulean blue paint on his frock coat. “Data, data, data! I cannot make bricks without clay!” says he.

His art material is this data, this clay—the details, the facts of the case which he has observed or ferreted out. But only Holmes creates these bricks which build up the solution. He creates a mental model of “what happened, who did it, how, and why?”

Let’s look at “creativity” from a philosophical, and then a practical angle.

Arthur Koestler in “The Act of Creation” presents us with the concept of bisociation—which he calls the foundation of creativity. Very roughly defined, it means taking two different planes of reference—world views, really, which are not normally associated—and viewing them at the same time. This reveals a previously unseen connection between them, which in turn feels altogether new.

On the simplest level, it’s a joke. Puns are good examples, with two worlds colliding and turning on a single word. Such as: “Clones are people two.”

Our reaction is “Ha! Ha!”

The second may be more scientific. This time the fresh thing is uncovered by the conscious search. It might be a recognition of a pattern, the discernment of complex interactions. A mathematic solution. A sudden insight that connects all the data we have been puzzling over, and then all falls into place, triggered by one final, last piece. Sherlock Holmes and that thumbprint in the closet in “The Norwood Builder”. Not just that it’s an obvious clue. But that it wasn’t there yesterday. That means the criminal is still at large. Directing the investigation. And local!

Creative discoveries made like those above elicit …. “Aha!”

And the third level is the highest form of human endeavor. A work of unmistakable genius, where the juxtaposition of materials and ideas or execution actually extend our notion of what is possible. We are transformed and transported by the experience of it. How can this even exist? It is a thing of beauty. Of wonder. A symphony. A painting. An eloquent mathematical proof. Has this been true all along? It evokes a feeling of connection to something much larger than oneself. Divine, some might call it. It takes us out of ourselves and admiration may be too pale a word.

Our response is “Ahhhhhhh!”

At this moment of creation/discovery scientists and artists may themselves laugh with pleasure. As Turing Award winner Alan Kay says, “the universe has always been there but we just didn’t see it.”

Holmes expresses his appreciation of this level of genius when he attends a concert of Sarasate playing Bach. And, as Watson says in The Valley of Fear of one of the smarter policemen who admires Holmes, “Mediocrity knows nothing higher than itself, but talent instantly recognizes genius.”

There is no question that a highly creative individual differs from their less creative colleagues. But the label of “artistic” in the late nineteenth century was not necessarily a compliment. While their works may have been admired, artists themselves were viewed as people who had their heads in the clouds, their hands on the absinthe or cocaine, and their personal lives veering toward a train wreck. Holmes was looked at as a bohemian, a renegade, an outsider.

The “artistic temperament” as it was called then was often a euphemism for emotional, lazy, flighty, manic, unreliable, and subject to moods. Artists dressed differently, they worked and slept at odd hours, and did not care for propriety. And who knew about their sex life? Scandalous, no doubt. The “artist” label was fraught then… and frankly, still misunderstood even today.

Someone who has never attempted to excel in an art form does not realize the sheer hard work it is to develop chops. Instead, non artists point to daydreaming, the contemplative hours, the apparent self-indulgence but miss the point. In fact, good artists have all learned how to work.

Art requires the challenge of intense focus yet the ability to simultaneously remain open. It also requires detailed specialized knowledge of materials, tools, techniques and subject matter.

In “The Greek Interpreter” we learn that Holmes’ grandmother was the sister of the artist Vernet. The eldest Vernet in this family of illustrious French painters created a very detailed catalogue of precise colours he used for seascapes and landscapes. He carefully mixed paints and then categorized and codified these tints for specific subject matter.

Sherlock Holmes’s art form is solving crime, and he has spent his adult life accruing the knowledge he needs—a mental catalogue of ashes, tire tracks, perfumes, and many other things which may turn up as indicators in his work. Reams of newspaper clippings detailing crimes and the motives and methods line his study. And he developed chemical tests—a reagent that infallibly detects human blood, for example.

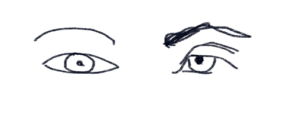

The mental discipline of art often requires a precise inner language to guide the act of creation. To continue with the visual metaphor, the great drawing teacher Betty Edwards in her seminal work “Drawing on the Right side of the Brain” points out that most people, as Holmes sometimes admonishes Watson, “see but do not observe”. When asked to draw an eye from memory, someone who hasn’t learned the trick might draw the symbol of an eye, as on the left, instead of the actual observed eye, which might look more like the figure on the right.

If a portrait painter can move past preconceived notions to the detail of what is actually there, s/he will “achieve a likeness” of the subject. (Note: I am not implying that drawing a likeness is the pinnacle of visual art, just that it’s an advanced drawing skill, acquired by training and by practice. Although Betty’s book will move you past that quickly).

As Goethe, one of Holmes’s favorite philosophers, says. “A person hears only what they understand.” Most people’s preconceived notions so block their perception that they fail to see or hear what is really there—because it is not what they expect, or what they already know.

Against all odds, artists must maintain a level of excitement, of enthusiasm for the act of creation that propels them on, and they must also have the ego to persist past early failure. One must sail right past the squawking early violin playing, the clumsy portraits, the muddy watercolours, that rough first draft of the novel. Acknowledge, improve, persevere.

In “The Sign of the Four”, as Holmes and Watson exhaustively trail their quarry, the doctor begins to fatigue, unable to keep up with Holmes. He says of his friend, “I had not the professional enthusiasm which carried my companion on.”

And that’s exactly the engine for all artists. The professional enthusiasm. Yes, Sherlock Holmes is not only a man of science, but he is unquestionably an artist as well.

***