Turpentine workers’ cabins. Valdosta, Georgia. 1937. Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

Turpentine workers’ cabins. Valdosta, Georgia. 1937. Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

The heart of my horror novel, The Hollow Kind, is the story of northern-born journeyman August Redfern, who marries into one thousand acres of longleaf pine forest. The year is 1917, the setting southeastern Georgia. Here, Redfern hopes to build a vast turpentine estate, but soon he discovers that the land he’s been gifted comes with a terrible price. His father-in-law, a timber baron who stole the land from poor farmers, has made a pact with a monster, and now the evil that dwells among the pines demands new tribute. Heedless of the past, Redfern plunges ahead with his venture, and within a year finds his wife and child struck low by the influenza pandemic, and his workers embroiled in a feud with ex-Confederates who claim the land is theirs. When a final act of sabotage threatens everything he’s built—and everyone he loves—Redfern is forced to bow to the entity in the woods, or lose the very land he’s bleeding dry.

Turpentine worker. 1937. Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

Turpentine worker. 1937. Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

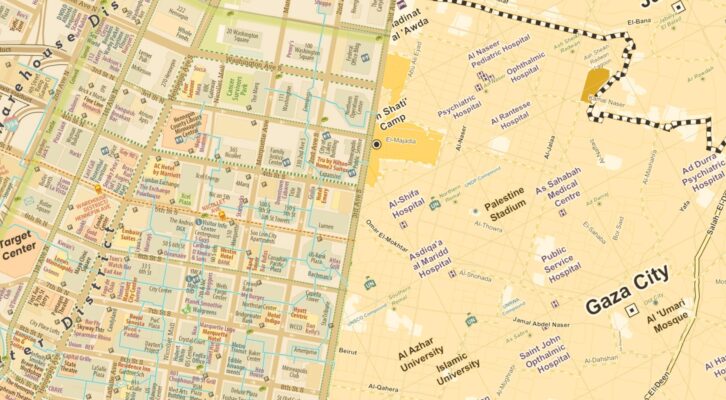

In truth, by the time August Redfern sets up shop at the turn of the century, most of the old pine forests of southeastern Georgia had been decimated by logging. I’ve lived in the region since 2007, and I honestly don’t remember the first time I heard about the Dodge Land Wars—or the Dodge Timber Wars, or the Dodge Land Troubles. Or “The Troubles.” My interest in the region’s history began with turpentining, harvesting a tree’s life blood for money. It seemed a ready made subject for a southern folk horror novel. It also resonated with me. I grew up in pulpwood country in south Arkansas, where pines were grown for the express purpose of being cut down. Researching the naval stores industry that drove coastal Georgia’s commerce after the Civil War led me to the longleaf pine itself, which in turn led me to the men who cut whole forests of them down in the late 1800s. Finally, The Hollow Kind took root when I came across the story of a local land agent named John Forsyth.

From The Atlanta Constitution, October 8, 1890:

SHOT DEAD BY AN ASSASSIN

J.C. Forsyth Murdered by a Secret Enemy Last Night.

MACON, GA., October 7—[Special.]—A report has been received here that J. C. Forsyth, one of the largest and best known lumber men in Georgia, was assassinated tonight at 7 o’clock, at Normandale, and died at 9 o’clock.

He was in his sitting room, and was shot through the window. The entire load went through the head. Forsyth was well known in Macon. He was expected [in Atlanta] tomorrow, where he frequently comes on business. The assassin is unknown … The party who shot Forsyth was in his bare feet, and is thought to be a white man. No cause can be given for the deed. Forsyth had no trouble with anyone for some time. His murder was a most cowardly crime.

Forsyth was superintendent of the Normandale Lumber Company, in which the Dodges are largely interested …

It was a rainy night, according to some accounts. Apparently, Forsyth had just retired from supper to smoke a cigar when he was shot-gunned in his rocking chair. His daughter, Nellie Forsyth (whose bravery, in part, inspired the heroine’s name in The Hollow Kind), rushed to his side, held him as he bled out in her arms. Later, it was discovered that a party of eight men had hired a North Carolina tree cutter to murder Forsyth. His crime? J.C. Forsyth was in the employ of a timber baron named William E. Dodge.

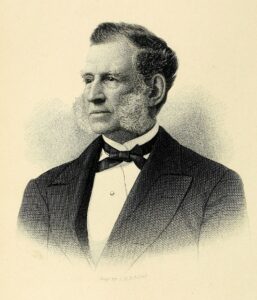

William E. Dodge, Sr. 1805-1883.

William E. Dodge, Sr. 1805-1883.

Dodge was a Connecticut-born man of influence. A famed politician, he was a Native American rights activist, President of the National Temperance Society, a founding member of the YMCA, and a wizard of Wall Street. In the years after the Civil War, Dodge and his sons bought up a defunct lumber company and used it to seize and log over 300,000 acres of longleaf pine in the wire grass region of Georgia. The Georgia legislature saw fit to name a county for him, though Dodge himself never actually lived in Georgia. His sons and partners ran the lumber business, among them a man named William Pitt Eastman, for whom the Dodge County seat of Eastman was named. In 1870, Dodge donated land to build a courthouse—land that was, some said, not his to give.

In fact, the Georgia Land and Lumber Company’s claims to the forests were wholly spurious. In 1842, the previous incarnation of the company had gone bankrupt. Northern creditors—among them the state of Indiana—assumed control of the company’s assets, including the Georgia land. But because taxes were never paid to Georgia by Indiana, the land holdings were forfeited and sold back to local families and landowners. When William Dodge and his partners bought the Georgia Land and Lumber Company in 1868, they did not recognize local claimants. By 1875, the pine forests—where deer had long roamed in large numbers and cattle and sheep grazed freely—were being cut.

Greene County, Georgia. 1937. Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

Greene County, Georgia. 1937. Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress.

Initially, the “squatters” evicted from the pines—families and farmers, mostly—took the Dodges to court, only to discover they were fighting within a rigged system. Thanks to a constitutional amendment and revised statutes following the Civil War, federal courts were given sway over state courts. As a result, land litigations against the Dodges were heard by federal judges, some of whom had northern interests. Inevitably, when the legal system failed, some of the locals—romanticized in written accounts as “one-legged Confederates and old widows”—took up arms to send the carpetbaggers “hellward.”

From the late 1800s well into the new century, in the small towns and denuded fields of a coastal plain once thick with forests, Georgia saw its own mini-Civil War play out. Men were forced to choose a side: work for the lumber company, or starve. Even today, families talk of great-grandfathers who chose the wrong side, great uncles who were strongmen, who scalped tenants short on rent and cut their throats, dumped their bodies in the confluence of the Ocmulgee and Oconee Rivers.

Longleaf pine near Waycross, Georgia. 1936. Library of Congress.

Longleaf pine near Waycross, Georgia. 1936. Library of Congress.

Inevitably, what gets lost in all this sordid history is the story of the trees themselves. Long before white people invaded the region, the forests of coastal Georgia served as tribal hunting grounds for Creek Indians. And long before cotton was Georgia’s cash crop, the longleaf pines stood millions-strong, some over a hundred feet tall. They had been here since the end of the Pleistocene. Eons ago, the Georgia coast resembled a midwestern prairie. It’s a mystery, how the land transformed into these verdant wire grass forests. Some speculate that the trees came as seeds on the wind, up from Mexico. With them came the indigo snake, the gopher tortoise, the Ivory-billed woodpecker. The pines thrived in the sandy soil and were strengthened by fires that burned when lightning struck, and after thousands of years of persisting, their whole ecosystem was destroyed by men.

In 1923, after five decades of feuds and murder, the last Dodge land case was settled in court. It involved almost four hundred litigants evicted by the Georgia Land and Lumber Company. In the end, the Dodges lost, but many of the original litigants were long dead, their descendants having fled the region. Like the trees themselves, they were ghosts.

***

Author’s note: The Dodge Land Wars have been widely documented, from plays to novels to dissertations, and this article owes a debt to a number of these sources. Foremost is The Dodge Land Troubles (1868-1923) by Jane Walker and Chris Trowell, as well as Ms. Walker’s novel, The Widow of Sighing Pines. Additional sources include archival issues of The Macon Telegraph, The Atlanta Constitution, and GeorgiaTrend magazine. Finally, for more fiction set in the region, see Eugenia Price’s The Beloved Invader (1965) and Brainard Cheney’s Lightwood (1939).