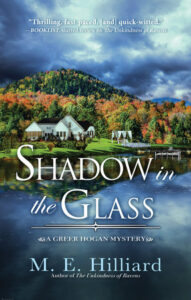

“I find nothing more relaxing than a country house murder. I was not particular about method. Poison was always good—there were so many options among common household products, not to mention the items found in the garden shed. Knives were a bit tricky unless you really knew your stuff; hit an artery and you have a lot of bloodstains to explain. Awkward. There were always old service revolvers tucked into desk drawers for those less concerned with noise. As far as blunt instruments went, I was a fan of the croquet mallet. There was a nice solid head, the shaft was long enough to give you a little insurance against the aforementioned bloodstains, and fingerprints could be explained away as long as one had the foresight to arrange a game on the day of the planned head-bashing, and remember your color when choosing the mallet of death. Really, the possibilities were endless.”

Greer Hogan

Shadow in the Glass

___________________________________

The country house murder has long been a staple of the traditional mystery. And why not? Most of us first encountered the joy of sleuthing in a stately manor while playing a childhood game of Clue. For some of us, an afternoon with a board game was a gateway drug to a lifetime of armchair detection. We roam imaginary mansions in the company of our favorite detectives, not letting our admiration for their skills eclipse our desire to be the first to solve the crime.

Agatha Christie published The Mysterious Affair at Styles just over one hundred years ago, and the country house murder has flourished as a subgenre ever since. Christie wrote several more, often basing the houses in her books on homes she’d lived in or visited. Marjorie Allingham, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Ngaio Marsh, the other queens of the Golden Age mystery, all contributed to the country house crime wave. Even Georgette Heyer, best known for her Regency romances, produced a series of country house mysteries, with such leading titles as Behold, Here’s Poison and A Blunt Instrument. Though the English country house was the standard, American authors such as Phoebe Atwood Taylor published their own take on it. Taylor’s Asey Mayo solves a murder of his host at a country home cut off by a snowstorm in Death Lights a Candle.

Though the period between the wars is most closely associated with the traditional country house murder, the form remains a perennial favorite. While the post-war fortunes of the home’s owners declined, the appetite for mysteries set in their hallowed halls did not. Perhaps now the guests are paying, in order to enable the owners to repair the leaking roof of the family mansion. Or the original owners are the guests of whatever parvenu scooped up the old manor house for a song, and relegated them to the gatekeeper’s cottage. It all adds to the tension, and the likelihood of a body or two turning up before tea time. The classic elements are unchanged, and it’s these that we look forward to.

The house itself, with the more utilitarian kitchen, bathrooms, and bedrooms supplemented by libraries, billiard rooms, conservatories, and studies, provides many scenes for the crime. Throw in the odd secret passage or priest hole, not to mention the exterior French doors that never lock properly, and a murderer’s means of escaping detection are assured. And let’s not forget the garden—easily accessed from multiple main floor rooms, containing hedges, reflecting pools, mazes, a shed, a summerhouse, and perhaps a trout pond or folly, and murder al fresco becomes all the more inviting. The body in the library is classic, but a body in the rose garden, the hayloft, or even stuffed down the laundry chute is also quite acceptable.

Choice of weapons in a country home are equally varied. In addition to the methods above, there always seem to be quantities of arsenic or cyanide lying around, not to mention decorative objects like candlesticks and ceremonial swords that multi-task as murder weapons. Outdoorsy? The ‘accidental’ shooting with a long gun while aiming at a grouse is always an option, as is drowning if you’ve got a good reason to be wet yourself. More exotic methods involving snakes, insects, or wild boar are harder to pull off, but also harder to prove.

Taken as a whole, the country house provides an embarrassment of riches to the homicidally inclined. And who might that be? Any good country house mystery will provide you with a slew of suspects. Though the butler doesn’t often do it, he and the rest of the staff must always be considered. There’s the imperious family patriarch or matriarch, the impatient heir apparent, the sketchy nephew or niece and the equally sketchy friend they’ve brought with them for the weekend, and someone’s old school chum or army buddy. And, of course, we’ve all got that one sister.

The victim is usually drawn from the same cast of characters, though we are occasionally treated to a mysterious stranger found dead on the property, a stranger who will turn out to be known to at least one of our suspects. Sometimes the crime occurs before the reader joins the action, as when the host is killed while his guests are still arriving, or before. The clever author will kill off your favorite suspect midway through the novel, challenging your deductive skills as the body count rises.

Detectives may be a guests or someone brought in by the local police, whose force is inadequate in the face of such a devious crime. Whether amateur or professional, they will winkle out the truth using reason and skill in eliciting information, rather than advanced forensics or technology. This is a plus for the reader, who doesn’t need any specialized knowledge other than that of human nature.

Science and technology do create some challenges for the contemporary author of country house murders. Readers will suspend disbelief to a point, but in an increasingly wired world where the smallest traces of evidence can be collected and examined, they need a reason to believe that the use of “little gray cells” will trump forensics. This is where setting is key. The country house is just that—a house removed from densely populated and therefore tech heavy areas. Put the mansion on an island or other remote location and spotty internet and cell service, as well as a dearth of the surveillance systems of modern society, are more easily explained. Have a storm come rolling in to strand you cast of characters, and then, just for fun, kill the lights, and you’re left with the key ingredients of the story without a lot of pesky modern conveniences to ruin the mood. Tessa Wegert does this skillfully in Death in the Family. G.M. Malliet’s Death in Cornwall uses a vacation area to equal effect.

Whether historical or modern, a well-crafted country house murder is a perennial pleasure. It’s the best kind of staycation—always clever and never gory, providing a chance to exercise our minds while exploring timbered halls, stately gardens, and secret passages without ever leaving home.

***