When you start out as a special agent for the FBI and get your first field office assignment, you’re pretty naive about certain things, especially if, like me, you had no previous law enforcement experience. The first thing you realize is that not everyone is glad to see you, and I’m not just talking about the bad guys. Some police departments welcome the assistance the Bureau can provide, while others perceive us as the four-hundred-pound gorilla muscling onto their turf.

When you’re new, you tend to assume that all PDs and sheriff ’s offices conduct complete and thorough investigations, just as you’ve been taught to do at the FBI Academy, and that all the evidence they give you is good and reliable. Well, that one isn’t always true, either.

It’s important to remember: We don’t catch criminals. That’s what the police do. What we do is assist local law enforcement in focusing their investigation on a particular type of unknown subject (or UNSUB, in our terminology). Depending on the type of evidence or clues available, we may be able to give pretty specific details of sex, race, age, area of residence, motive, profession, background, personal relationships and various other aspects of an individual’s personality. We will also suggest proactive techniques to draw a criminal into making a move to go in a particular direction.

Once the suspect is apprehended, we can aid in interrogation and then prosecution strategy. In the trial, we can provide expert testimony of signature, modus operandi (MO), motive, linkage, crime classification and staging. This is all based on our research and specialized experience with what is now tens of thousands of cases, many more than any local investigator could ever possibly see. Essentially, we use the same techniques as our fictional forebear, Sherlock Holmes. It is all based on logical, deductive and inductive reasoning and our basic equation is this: WHY? + HOW? = WHO.

It sounds simple, but there are countless variables that go into the analysis; and to be truly useful, we have to be as specific as possible. We all recognize the cliché of the white male loner in his twenties. But even in instances where that description might be accurate, it doesn’t help much unless we can say something about where he lives, what’s been happening in his life, what types of changes family, friends and colleagues should be noticing in him, when and where he might strike again, whether and/or how he’ll react to the investigation, etc.

One thing I always told new agents in my unit was that it is not enough to profile the UNSUB; you have to profile the victim, too. You have to know whether she or he had a high-risk lifestyle, whether she or he was likely to be passive or aggressive in the face of threats, whether she or he had any enemies or bad relationships in the past, and so on. But I’ve found that even that is not enough.

You also have to profile the situation. And by that, I mean taking a look at what is going on in and around the investigation. What is the social environment like? How do people feel about the particular crime? What role do the media play? What is the police culture like? There are any number of important questions you can ask to try to get the lay of the land.

In his 1936 memoir essay, “The Crack-Up,” F. Scott Fitzgerald observed: The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. For those of us in law enforcement who at least strive for a first-rate intelligence, criminal justice provides an ultimate challenge: How do we vigorously hunt down criminals and prosecute and punish crimes, while trying to make sure that no innocent person suffers at the hands of a sincere but imperfect system, administered by practitioners representing every one of our collective human faults and foibles?

When I was a kid, there was a television series that virtually every boy and many girls of my generation will recall. It was the Adventures of Superman, and in the intro, over a tableau of the superhero posed, hands resolutely on hips, in front of a waving American flag, the narrator proclaimed how he fought “a never-ending battle for truth, justice and the American way.”

When I began my law enforcement career in 1970, along with most of my colleagues, I believed that truth and justice would always prevail. Regardless of the jurisdiction or individual law enforcement agency, we were all playing on a level field. As investigators, I believed, it was our job to help solve crimes and apprehend criminals using all of our skills and every investigative tool available to us.

In retrospect, I was somewhat naive. It is not a level playing field, and all investigators and agencies are not equal. I still believe that the overwhelming majority of us are dedicated to following the letter of the law and our own personal codes of conduct. Unfortunately, as in any other profession, there are some individuals and departments that believe they are performing their jobs properly when, in fact, they are using faulty, outdated and sometimes illegal techniques and practices.

It has taken too many years to realize and accept that while our justice system is still the best in the world, it is far from perfect. And I now wonder about some of the cases my colleagues and I received from law enforcement agencies within the United States and worldwide. Did the investigators effectively contain and control the crime scene? Did they effectively collect and preserve evidence, avoid contamination and maintain chain of custody? Were the medical examiner and/or forensic pathologists adequately certified, and were specimens correctly evaluated? Were interviews and interrogations conducted without leading or coercion? Was the prosecutor influenced by any factors outside the case itself, such as reelection or political ambition?

For some cases, I now have to wonder: Did I get it right? And that will always be a troubling question.

That, in a nutshell, is what we’re dealing with. And that is why we all must be vigilant and involved and questioning to see that the system works as well as it can.

Which brings us back to Superman and his never-ending battle.

None of us is Superman, but by the very nature of the challenge, this pretty much has to be a “never-ending battle.” Within a system that must be administered fairly and uniformly, we must never lose sight of the individual aspects: the individual victim, defendant and facts of the case. In so doing, we reach an understanding of appropriate responses in each situation.

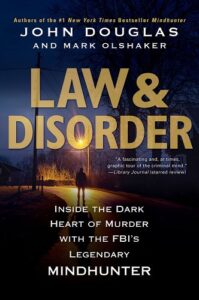

The investigations, research and writing of Law & Disorder have made me realize how vulnerable any of us can be when the system goes awry. When that happens, the system can take on a life and momentum of its own, just as powerful and potentially devastating as when it functions properly. It’s also forced me to look back at some of my earlier cases and reflect on some of the assumptions under which I operated. First and foremost, when a local law enforcement agency came to us for assistance, we had to assume that they were providing us with good data. On cases where I was actually able to get out into the field, I could make my own evaluation. But when all of the information was presented to us, we were limited. In most situations, that didn’t matter because we had the key elements we needed, such as crime scene photos, descriptions and victimology.

I would also recommend several steps that could help prevent innocent men and women from facing incarceration and execution.

First, I advocate an independent national forensics lab, separate from the FBI and all other law enforcement agencies. Despite previous documented problems, I strongly believe in the current excellence and integrity of the FBI National Laboratory, now located in a modern facility at the Academy in Quantico. But with potential death penalty or other serious cases, there should be no question of influence or hidden agenda. It is still possible for an investigator to convey subtly to someone in the lab that this particular piece of evidence is critical to the case, or that the jury has to be able to understand a certain fact in unequivocal terms, or any of a number of other requested outcomes.

Also in the realm of evidence, we have seen that too many confessions are coerced or in some other way are not legitimate. I would therefore require that all police interrogations be recorded—preferably video, as well as audio—in full. If this is not done, the evidence should be inadmissible in pursuit of a death penalty eligible verdict. Signed written confessions should not be sufficient.

One of the recurring arguments against the death penalty is the incredible amount of money expended on seemingly endless appeals. There are various estimates on how much it costs to get a convicted defendant to the point where he can be executed, but most of them are in the seven-figure range. In this age of diminished resources, that is not a sum to be trifled with. A similar argument can be made for any case where a long appeals process is likely.

On the other hand, if we could reform the issues that cause wrongful or questionable convictions and solidify public confidence that we have done so, think of how much will be saved by not having to go through the extensive efforts required to cure wrongs.

There is no trustworthy and effective national governing body with objective standards that certifies experts in all of the key forensic areas, such as odontology, fingerprint identification, hair and fiber, ballistics, and so on. If a judge concludes that someone is an expert, the jurors are naturally inclined to put a good deal of weight on that individual’s testimony.

By the same token, if a judge so decides, he or she can prevent another individual from offering a learned opinion. Then, if the defendant is convicted and later found not guilty based on the reexamination of faulty forensic analysis, investigators, prosecutors and judges will often say that the jurors heard the evidence and they determined that the defendant was guilty. This kind of irresponsible projection is a neat way for them to alleviate their own responsibility and place blame on the operation of the jury system.

Ultimately, one of the things that most bothers me in dealing with miscarriages of justice is that these mistakes force us to divert focus from the victim of the crime, which is where I always feel it belongs. By rushing to judgment, taking convenient shortcuts and ignoring evidence, law enforcement officials make innocent defendants into new victims, and thereby deny justice twice.

It all comes down to this: Whenever theory supersedes evidence, and prejudice deposes rationalism, there can be no real justice.

***