From the beginning of the motion picture, artists have used the form to depict acts of violence, while moral scolds sought censorship. Over the past several weeks, there has been a noticeable uptick in vocal outrage directed at artists and media conglomerates as a result of cross-partisan condemnation and scapegoating in the wake of the latest mass shootings.

It hasn’t stopped at political stumping, either: one film, Blumhouses Productions’ dystopian thriller The Hunt was indefinitely shelved (read: effectively censored) to appease the backlash (although it also fell victim to a bad faith campaign led by conservative ideologues).

Meanwhile, debates continued to rage online and in print over the moral implications and potential consequences of violence showcased in recent and upcoming releases such as Once Upon a Time in Hollywood and Joker.

Those who defend the rights of artists and entertainers to employ violence as they see fit continually reminder detractors of the necessity of free speech and the difference between depiction and endorsement, to little avail. Those arguments—essential and accurate though they are—carry little water in today’s ultra-polarized landscape. Part of their failure stems from an unwillingness to acknowledge a disturbing, but essential truth about the representation of violence in film: that it can, in the right context, provide a deep sense of visceral, emotional and psychological catharsis.

This type of violence is difficult to define. I am not referring to the simple release of endorphins that comes with watching a masked killer pick off nubile teens or a badass action hero blow away faceless thugs. The would-be censors are quick to point to those examples, and while their arguments about their effect on viewers remains weak, it can’t be denied the titillation factor and general lack of empathy is often taken for granted by audiences.

True violent catharsis actively engages the viewer, forcing them to be aware of their reactions without indicting them (like Taxi Driver, A Clockwork Orange or Funny Games). They acknowledge our desire for a balancing of the cosmic scales of justice and our primal sense of bloodlust, quenching our thirst for both.

What follows are ten of the most shocking, powerful, surprising, and all-around cathartic examples of cinematic violence.

(Warning: massive spoilers abound.)

Inglorious Basterds / Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Despite what some critics would have you believe, Quentin Tarantino has always been interested in the intricacies and complexities of onscreen violence, but it wasn’t until 2007’s Death Proof, that he figured out how to tap into the medium’s potential for righting historical wrongs and societal evils, providing audiences with some small—and no doubt fleeting—measure of emotional amelioration.

In both his action-packed 2009 World War II epic Inglorious Basterds and his most recent release, the nostalgic ‘60s showbiz drama Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, Tarantino alters historical record to give real-world figures of atrocity (the Nazis and the Manson Family, respectively) their just desserts. The visceral thrill that comes with buying into this revenge fantasy can’t be denied, and it’s no surprise these two films are his biggest hits to date.

Deadwood: The Movie

The original three-season run of HBO’s noir-western Deadwood mixed sensitive character study and complex social insight with brutal bursts of two-fisted action; leads Al Swearengen, Seth Bullock and Charlie Utter dispensed harsh frontier justice on any number of deserving [expletive deleted]—but since this is a list of movie scenes, we best go with one from this year’s conclusory film.

Towards the end of the film, series arch-villain George Hearst is nearly lynched by a mob of rowdy “hoopleheads,” the town’s labor pool the murderous mining magnate has long exploited and terrorized. Although he is saved at the last moment—and despite the fact that nothing of the sort ever happened to the real George Hearst (who, from all accounts, wasn’t quite the monster the show portrays him as, although he certainly sired monstrous offspring)—it is a moment that, like Deadwood: The Movie itself, was long overdue, but well worth the wait.

Matewan (1987)

John Sayles’s criminally underseen coal-country drama Matewan (1987) makes for the perfect companion piece to Deadwood: The Movie, what with its mining town setting, large ensemble cast, poetic aesthetic and fatalistic tone, and, most importantly, deep empathy for America’s workers and even deeper antipathy for its industrialist rulers.

Like Deadwood, Matewan gives viewers the satisfaction of watching Pinkerton agents (members of a private security force employed throughout the late 19th-early 20th century as strike breakers and labor saboteurs) get blown to smithereens.

The film is ultimately a tragedy with a pacifist spirit, but the elation of watching a town of exploited workers take up arms against company gun thugs can’t be denied or condemned.

Sankofa

Set mostly on a sugar plantation in Louisiana in the days of chattel slavery, this 1993 magic realist slave drama from Ethiopian director Haile Gerima similarly builds to a prolonged scene of violent overthrow, although the film is less about rebellion and more about the importance of reclaiming one’s cultural history.

That said, the third act sequence, where a group of slaves stage their revolt, murder their masters and burn down their plantation, remains one of the most haunting, but emotionally purifying sequences in the last 30 years of cinema.

Dogville

Ostensibly a critique America’s exploitation of its working poor, Lars Von Trier’s Dogville is in actuality an examination of humanity’s potential for evil. Like several of the Danish iconoclast’s other films, it is a passion play, albeit one ending not in martyrdom, but measure-for-measure repayment on an apocalyptic scale.

In the film’s final act, our hero, long-suffering gun moll turned would-be saint turned avenging angel Grace (Nicole Kidman) has a choice to make: she can forgive the denizens of Dogville for the months of physical, sexual, and psychological abuse to which they’ve subjected her…or she can direct her mob boss father’s army to, in the words of the film’s narrator, “put it to rights.” She chooses the latter.

The following massacre should, by all rights, play out as nightmarish tragedy, but in the hands of the ever-transgressive Von Trier, it makes for a viscerally thrilling, at times beatific realization of revelation.

King of New York

When it comes to the cinema of transgression, one of the few filmmakers who can touch Von Trier is Abel Ferrara. The notoriously hard-living and outspoken director is most closely associated with his graphic and gritty examinations of New York street life, although his most popular and well-known film is King of New York, his slick gangland drama from 1990. Despite mainstream appeal, it retains Ferrara’s punk-rock attitude, transposed through the aesthetics of early gangsta rap.

In the film’s most memorable set piece (which earns it entry here), anti-hero drug kingpin Frank White (Christopher Walken) gets revenge for one of his fallen soldiers by doing a drive by on a cop in the middle of another cop’s funeral. In any other film, this would be portrayed as an act of ultimate evil, but here it’s a fist pumping shotgun blast of anti-authority sentiment.

Vigilante

When drawing up this list, I made a conscious effort to exclude straight revenge thrillers, since, like slasher flicks or martial arts movies, violent retribution is what you expect going in. As a result, the catharsis offered is usually a different variety.

That said, I’ve made an exception for William Lusting’s 1983 exploitation gem Vigilante. On the surface, the film appears to be your standard Death Wish rip-off (a soft-spoken suburbanite turns into a cold-blooded killing machine after his family is assaulted by a gang of urban street toughs), but sets itself apart with a jaw-dropper of an ending: the hero assassinates a federal judge (who admittedly screwed him over earlier).

With this final act of violence, Lusting expertly spins the film’s reactionary philosophy into a radical one.

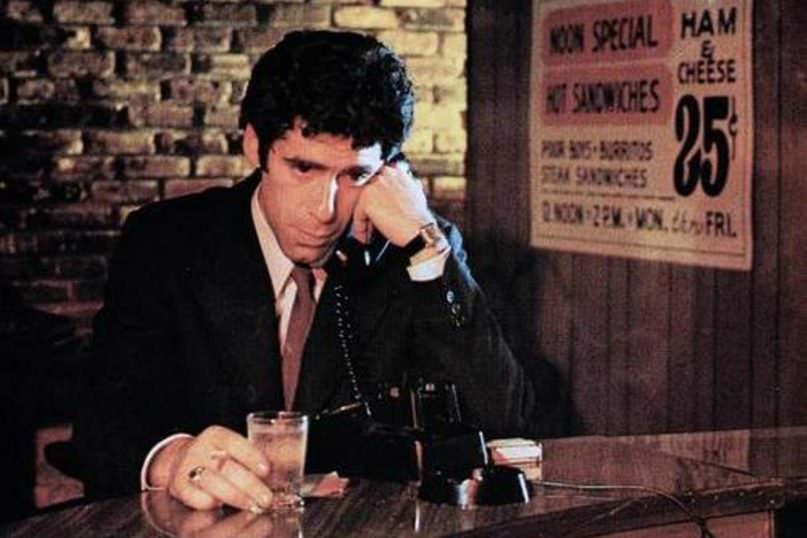

The Long Goodbye

Speaking of fist-pumping endings, nothing beats Robert Altman’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s penultimate Philip Marlow novel. Altman takes Chandler’s archetypal private dick (Elliot Gould steps into Bogie’s shoes and brilliantly reinterprets the character) transporting him, Rip Van Winkle-style, from 1953 to 1973.

Along with the obvious changes in setting and style, Altman’s film deviates from the ending of original novel; Marlow—who, throughout previous novels and film adaptations, killed rarely and only ever in self-defense—shoots down his wife-murdering best friend in cold blood.

It’s a startling moment, and Gould plays it with a perfect mixture of grim determination and righteous satisfaction. The viewer empathizes with the moral compromise Marlow makes, even as they relish the proportionally appropriate moral recompense.

The French Connection

Not all examples of violent cinematic catharsis stem from audience’s longing for moral redress; sometimes, they’re the result of giving a great set-up a killer payoff. Such is the case in William Friedkin’s classic 1971 police procedural: shot on location (and minus several necessary permits), the film’s jaw-dropping car/train/foot race through the crowded streets of Brooklyn concludes with dogged detective Popeye Doyle shockingly putting a bullet in the back of a murder suspect as he turns to flee.

Initially, the studio worried Hackman’s character came off as too ruthless and demanded Friedkin shoot a new ending to the scene. Eddie Egan, the real-life cop who served as the main inspiration for Doyle, was also opposed to it, claiming that he’d never shoot an unarmed suspect in the back.

However, when the scene was met with spontaneous and rapturous applause by test audiences, all parties withdrew their objections and that moment of violent release would go become the centerpiece of the film’s advertising campaign, as well as one of the most iconic shots in all of ‘70’s cinema.