The New York City subway system has remained relatively unchanged since the 1970s. This an easy initial takeaway of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, a 1974 film about a subway train hijacking that might have aged into an interesting relic of an earlier, analog time in New York City’s history if so much about the film didn’t feel very aesthetically, even emotionally, familiar.

A sleek 2009 remake starring Denzel Washington and John Travolta insisted that a technological gulf separated the post-millennium city from its 1970s counterpart, but even following the MTA’s inclusion of sophisticated telecommunication systems (such as the Communications-Based Train Control, or CBTC, signaling system that was first installed on the L line in 2000), the experience of the New York City subway system didn’t change that much for the great many not working in its control rooms.

If you ride the subway in 2022, you might as well be riding it at any other point in time. Indeed, to ride the subway in New York is to participate in a kind of temporal chiasmus—a sequence of experiences that seems to develop as it goes on but is simply repeating and reshuffling the same components over and over. The Taking of Pelham One Two Three takes place nearly fifty years ago, and yet nothing about its representation of the subway experience feels dated.

Some of this is because of the setting; the variety of train cars which features prominently in the film is aesthetically similar to the kind used today on the IND lines (the A, C, and E trains). The film was shot in a real subway tunnel near the defunct Court Street station on the Fulton line in Downtown Brooklyn (a location which is currently home to the underground New York Transit Museum).

But it’s mostly because the film captures that unique, ineffable aura of the New York City subway system, an aura that has apparently defined it through these many years. In The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, the subway is cumbersome, inefficient, inconvenient; it is dirty, dilapidated, and neglected; it is stressful, exhausting, and dangerous. The Taking of Pelham One Two Three represents the subway for what it truly is: a paradox, a massive and sophisticated public transportation network in a famous city, in charge of carrying millions of people to their destinations every day, pathetically held together by rust and the strenuous labor of a handful of beleaguered—and no doubt severely ulcerated—civil servants.

Indeed, because it shows the subway in a temporary, phenomenal state of disaster, the film also can’t help but represent the subway on the whole as a miracle; that it is even able to run at all, let alone do it so successfully almost all of the time is genuinely amazing. The film walks a line, tonally, between complete and utter frustration at the subway, and a grand admiration for the entire thing and the workers who keep it going. This is the natural tonal baseline of New York, itself: a love/hate for this essential piece of infrastructure, New York’s clogged-but-chugging artery system, equally its lifeblood and its heartburn. You find me a film with more verisimilitude, and I’ll lick the wall of a train car. (I will not do this.)

All the same, a film’s presentation of a resonant simulacrum isn’t on its own a measure of the quality of that film (although, ahem, that the simulacrum is so realistic after five decades seems to suggest something about the quality of the subway.) But the incredible detail by which the subway system is rendered—which includes scenes of characters describing routes, procedures, apparatuses, chains of command, and (albeit simplified) fail-safe strategies—represents it as harrowing for all who encounter it. It is a giant, ungainly body, a thing that—without constant vigilance—could easily give way to chaos.

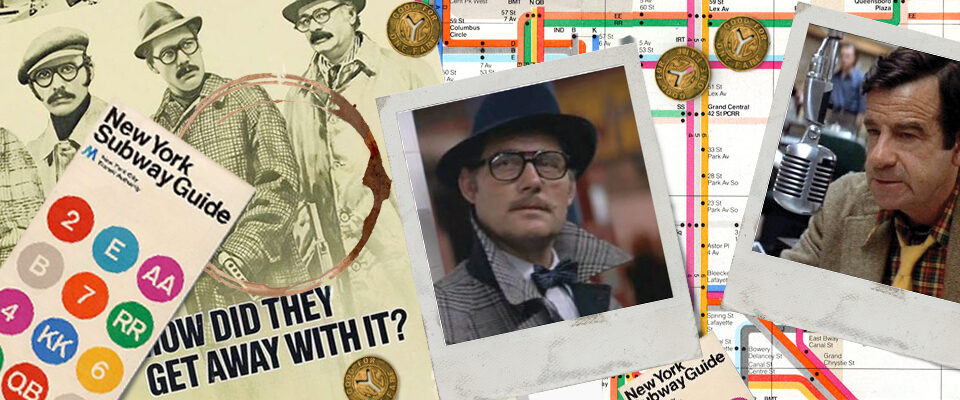

The film, which was directed by Joseph Sargent from a screenplay by Peter Stone and based on a 1973 novel of the same name by John Godey, begins on an ordinary afternoon, when several disguised, armed men—”Mr. Green” (Martin Balsam), “Mr. Gray” (Héctor Elizondo), and “Mr. Brown” (Earl Hindman), all under the command of “Mr. Blue” (Robert Shaw, a year after The Sting and a year before Jaws)—board a downtown bound 6 train and take it over. (The train has departed from Pelham Bay in the Bronx at 1:23 pm, so “Pelham 123″ is the code name that dispatch uses to communicate with the driver). The hijackers separate a single car from the rest and hold its twenty-sum-odd riders hostage in exchange for one million dollars. The city is unprepared for such a circumstance (even though the 70s were a golden age of hijackings, though of airplanes) and it takes a while for the MTA to compose itself. Not long after Mr. Blue announces his demands, a member of the transit police named Lt. Zachary Garber (Walter Matthau) radios in, becoming the primary negotiator. As he and his colleague, Lt. Rico Patrone (Jerry Stiller) race to fulfill the hijackers’ demands, Garber does everything he can to figure out how to nail them.

If this sounds like a perfect movie, it’s because it is. The gambit is tight and follows a set of rules: the hijackers’ plan is simple, but can be thrown out of whack by the behavior of the many participants. In a film that is so much about how “the subway” is operated by humans rather than as a coordinated network of autonomous machines, the relationships in Pelham are the most important part. The dynamic between the hijackers, particularly Messrs. Blue, Green, Gray (Brown is just window dressing and doesn’t do much) is a perfect formula for this kind of potential volatility—one of them is a calculating leader, one of them feels guilty and has second thoughts, and one of them is a psycho. But nothing is more compelling than the relationship between Matthau’s negotiator and Shaw’s criminal, speaking to one another over the train radio—the two actors allow themselves to be ever-so-slightly amused by one another. They’d even possibly respect each other if they had met under different circumstances.

The movie also excels in its drawing of the ensemble of MTA workers caught up in the disaster: an assortment of profoundly ordinary, shouting middle-aged men who probably can’t wait to earn their pensions and finally get out of the brown, windowless room where they spend each day making sure trains don’t collide with one another. And with his dry wit and a slightly exaggerated version of his own Brooklyn accent, Walter Matthau is perfect as their tired, maybe even hangdog, wiseguy of a leader—who is introduced as he is giving a tour of the MTA’s control room to a group of engineers from the (more) pristine Tokyo Subway system. These gentlemen are all elegantly dressed, well-mannered, respectful (and also bilingual), whereas Garber, wearing a brown suit, a plaid shirt, and a bright yellow tie, is by comparison the human equivalent of a mustard stain.

There is no actor finer than Matthau at locating the colorfulness in ordinariness; he always finds a prop to fiddle with slightly, a fellow character to develop a subtle annoyance with, a word to get stuck on a few times. His characters give the impression that they find ways to amuse themselves amid their humdrum or even disagreeable occupations. They often turn out to be great masterminds or a last line of defense, but they are simultaneously regular joes who would probably prefer to be somewhere else. Garber is one of Matthau’s most lightly laconic characters, aware of the madness around him, irked by it, but also not without affinity for it. (Rather like most New Yorkers, I’d wager, when it comes to the subway itself.)

Garber knows what the reality of the subway is; he deals with it, and that also means he takes responsibility for it. It’s important to his character that he’s not assigned to be Mr. Blue’s contact in the control room; he takes the radio microphone and starts talking to Mr. Blue out of professional, but also moral, obligation. He grows agitated at the other cranky subway personnel who get in the way. Mr. Blue gives Garber one hour to have the money delivered to the train, with the promise that for every minute they are late, he will start shooting passengers. Garber understands that the fate of these people rests on his shoulders; as the situation grows more precarious, he begins to unravel a bit—shedding layers and loosening his tie—trying not to lose his long-cultivated cool.

The genius of Pelham is that it represents the everyday world of the subway while it tells the story of an exceptional, unprecedented event.The genius of Pelham is that it represents the everyday world of the subway while it tells the story of an exceptional, unprecedented event. The story of the control room is as much an intense hostage negotiation as it is a workplace comedy. Its characters have known each other for years; they have rapports, even friendships. Jerry Stiller’s Rico, a slacker who has wound up in charge for some reason, projects an unhinged serenity with the whole affair; “What’s up, Z?” he asks Zachary Garber every time Garber radios over to him with an update, as casually as he’s asking for the baseball score. After Caz Dolowitz—a sweaty, swearing veteran control tower operator—winds up an early casualty, Garber’s coworkers grow angry at him for negotiating with the terrorist Mr. Blue, the “murderer” of “Fat Caz,” their longtime colleague.

“Solidarity” is the theme that welds the film together on its most basic level. The MTA employees are loyal to one another, as are the police officers who become involved on the ground. The hostages on the subway car—a melange of people from different backgrounds and of different ages—become, by circumstance, defined by their togetherness, even maybe their sameness. Probably to represent the New Yorker-ishness of these passengers, none of the hostages stay quiet when the hijackers take over, asking them a million questions and expressing their discomfort. Most memorable, for me, is that other subway dispatchers on their radios seem just as stressed by their daily job of routing trains as Garber does negotiating for the safety of twenty captured civilians. The film takes place in a single day—it is, for everyone, an extremely long, hard day at work.

But we find out later in the film that Mr. Blue is a career mercenary; he has no sense of loyalty, no sense of obligation to his fellow man. Mr. Green, the crew’s ringer (the only one able to actually drive the train) is revealed to have been a motorman fired on suspicion of trafficking drugs; angry and wanting his due after driving a train for so many years, he signs on to this dangerous venture with only his self-interest in mind. Mr. Gray, is revealed later, to have been kicked out of the Italian Mob for being deranged; a free agent, he is no longer bound by a bond to any particular group, either. The incompetent New York City mayor is revealed to be no better—complying with their demands not to save the lives of twenty citizens, but to try to make himself look good to voters.

The MTA in the film is, therefore, represented as the good guys, which they don’t often get to be in the narrative of everyday life. But the film does not forget that New York’s vast subway system is one of the most democratic institutions in the entire city, let alone the world—not only for its being, fundamentally, a system of wide-reaching, flat-fare mass transit, but also for being something that most everyone in New York has to deal with. When the film was released, Nora Sayre, writing in The New York Times, observed that “Throughout there’s a skillful balance between the vulnerability of New Yorkers and the drastic, provocative sense of comedy that thrives all over our sidewalks. And the hijacking seems like a perfectly probable event for this town. (Perhaps the only element of fantasy is the implication that the city’s departments could function so smoothly together).” It is a film that captures all our feelings about the transit system, then and now, and that is no small feat.

It’s true that the real-life MTA wanted the subway experience to seem as nice as possible, to appeal to potential real-life riders (and to counteract the negative press potentially generated by the story of a subway hijacking). The Transit Authority agreed to allow the crew to film in the real subway tunnels if they promised not to show any of the graffiti lining the walls. Sargent, the director, acknowledged in an interview, “New Yorkers are going to hoot when they see our spotless subway cars. But the TA was adamant on that score. They said to show graffiti would be to glorify it. We argued that it was artistically expressive. But we got nowhere.” There are also no rats or roaches in the film, which is also funny, especially since the film set was beleaguered by them. Matthau said, of his one scene in a real subway tunnel itself, “There are bacteria down there that haven’t been discovered yet. And bugs. Big ugly bugs from the planet Uranus. They all settled in the New York subway tunnels. I saw one bug mug a guy. I wasn’t down there a long time—but long enough to develop the strangest cold I ever had. It stayed in my nose for five days, then went to my throat.” Shaw’s biographer John French wrote that “There were rats everywhere and every time someone jumped from the train, or tripped over the lines, clouds of black dust rose into the air, making it impossible to shoot until it had settled.”

Rats or no rats, though, the grunge of New York City (especially during the famously dirty 1970s) shines through. It is a visceral film—perhaps even more for its capturing the indescribable essence of greatness and chaos born by the subway system itself than its successful enactment of a tense, nerve-wracking story. But mostly, it captures a strange heartbeat of New York City: of throngs of people (mostly) working together to make sure that everybody makes it through the day. So then we can all get on the subway and go home.

*This article has been updated to clarify that the specific model of train car used in the film is not currently used today.