When we speak of modern crime fiction masters names like James Ellroy, Megan Abbott, Sara Gran, Denise Mina, Walter Mosley, Don Winslow, Attica Locke, Reed Farrel Coleman, Tana French, and Daniel Woodrell usually pop up. If the conversation moves beyond that and pushes into international territory, then Fuminori Nakamura, Leila Slimani, Hideo Yokoyama, Leonardo Padura, Claudia Piñeiro, Teresa Solana, Tonino Benacquista, and Patricia Melo enter the conversation. However, there’s an author who’s a pillar of crime fiction in Latin America and Europe who doesn’t normally get the recognition he deserves: Paco Ignacio Taibo II.

Taibo was born in Gijon, Spain in January 11, 1949. His family were leftists and very politically engaged. In fact, in 1958 they had to leave Spain and move to Mexico fleeing Francisco Franco’s dictatorship. The event seems to have shaped Taibo in many ways. In the following years, he was a militant student and ran away from three different schools. Luckily, he was attracted to writing from an early age. Soon after his militant days ended, Taibo became a journalist and, eventually, a professor.

Despite his interesting beginnings, what makes Taibo a name that should be mentioned whenever superb crime fiction is discussed is his talent as a storyteller and the fact that he was singlehandedly responsible for the creation of the “neopoliciaco” genre in Latin America. A mix of noir, police procedural, and politics, neopoliciaco brings together the best elements of crime, thrillers, police procedurals, mysteries, and noir while also critiquing governmental corruption and constructing narratives that explore the system that’s to blame for placing individuals in socioeconomic spaces in which crime is often the only way out. Despite all this, Taibo’s work is fun and exciting and never feels preachy.

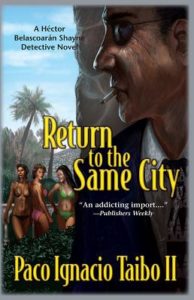

Taibo writes essays, novels, nonfiction, short stories, and everything in between. He is well known for his research and politics and how those two elements have a huge impact on his writing. However, the pillar of what he does best, the core of what earns him a spot as one of the best crime writers of our time, are the Hector Belascoarán Shayne novels, which include An Easy Thing, Some Clouds, Return to the Same City, Frontera Dreams, and The Uncomfortable Dead, which Taibo co-wrote with Subcomandante Marcos, the former leader of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation. The Belascoarán Shayne series has been translated into many languages, won awards in various countries, and, perhaps more importantly, inspired new generations of writers to break away from some of the formulaic elements of PI novels to create narratives that take into consideration local politics, the lives of citizens on society’s bottom rung, and philosophy, all while keeping the occasional dark humor that makes noir and PI novels a treat to read.

Belascoarán Shayne is a classic gumshoe who spends a lot of time in his head, thinking about the way everything he observes relates to everything else. However, he is also a very philosophical man and is obsessed with politics and how they trickle down and affect all citizens through the creation of a system that makes the rich richer and keeps the poor fighting poverty forever. In the novels, Belascoarán Shayne, who walks a lot, uses public transportation, and constantly observes Mexico City, shares his office with a wide array of people who work normal jobs. They all have grievances to air with the government, and that allows the PI to do the same, and he does it often. Through Belascoarán Shayne, Taibo dissects politics and attacks corruption while simultaneously giving readers a top-notch chronicle of the street life and idiosyncrasies that make up Mexico City. This obsession with chronicling the city has made Taibo one the best, clearest, most honest voices in Mexican fiction, and an author who brings the country, and especially Mexico City, to readers unfiltered. In Return to the Same City, Taibo writes a line that encapsulates what he does so brilliantly in most of his work: “We experience different cities, linked by the abuses of power and fear, corruption, and the eternal threat of descent into the jungle that hides in the system; it pops up regularly to remind us that we are fragile, that we are alone, that one day we will be fodder for the buzzards.”

While the depth of Taibo’s work merits study, his novels deserve to be read simply because they are extremely entertaining. There’s dark humor covering everything, and Belascorán Shayne is a flawed character that’s as likeable as he is cynical. He takes things to heart and is always looking for connections, or for the next case, while looking out his window and enjoying the little things that the rest of us enjoy. There’s a passage early on in No Happy Ending that exemplifies this perfectly, and that works as a introduction not only to Belascoarán Shayne as a character but also to Taibo’s voice, passions, rhythm, and favorite topics:

“What the hell did all this have to do with him? He wasn’t working on anything, he’d spent the last two months in a kind of quasi-Buddhist contemplation of the downtown streets, going on endless, meandering walks, poking around tenement buildings, hunting for bargains in second-hand bookstores, watching the clouds or the traffic from his office window. Two months waiting for something that was worth getting excited about. And now this: two dead men and a plane ticket to New York to keep him from sticking his nose in where somebody thought it didn’t belong. But if they didn’t want him to get involved, then why the hell had they gone and dumped a dead Roman in his bathroom, and then sent him the photograph of this other guy?”

I love to read work that knows where it fits in the literary landscape. When an author recognizes what came before and how they are walking in new directions in the same field, it is easy to see how what we read is often a new and exciting branch of the same tree. Taibo is fully aware of the crime and PI literature that came before him, and he engages with it from time to time while never losing his unique sense of place, undeniable humanity, and gritty uniqueness. In The Uncomfortable Dead, there is a tip of the hat to the interconnectedness of the genre that comes from literature filtered through images:

“Hector opted for silence. Just a couple of months before, he had gone to a video club and rented a series created by Alec Guinness based on a novel by le Carre, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, produced by the BBC, and for six continuous hours he had watched in fascination as Smiley-Guinness used the most effective interrogation technique in the world: putting on a stupid face (if the guy weren’t British, Hector would say he was the biggest jerk he’d ever seen) and staring at people languidly, not too interested, like he was doing them a favor, and people would just talk and talk to him, and once in a while, a long while, he would drop a question, as if not really caring much, just to make conversation.”

Paco Ignacio Taibo II is the father of the neopoliciaco genre and one of the most talented and historically educated chroniclers of Mexico City. However, fans of crime fiction should read him because he has a soft spot for everyday people and a fist of anger always ready to attack injustice and defend those who, through their everyday hustling and menial jobs, keep Mexico City functioning. Crime fiction has humanity, not crime, at its core, and Taibo’s understanding of this, as well as his knowledge of how crucial empathy is to augment the significance of things like murder, makes him a vital voice who has left a mark on the history of the genre. We are lucky to have most of his work translated into English, so if you want to walk the streets of Mexico City and see it through the past four decades, Taibo is the perfect companion, teacher, and tour guide.