When the television show Charlie’s Angels debuted on ABC in 1976, at the height of the second wave feminism movement, it presented a chafing double-bind of female representation: a portrayal of tremendous female independence, capability, and power that was simultaneously loaded with objectification and sexualization. The show, which ran from 1976 to 1981 and reached 59% of American households at the peak of its syndication, chronicled the fun adventures of three beautiful young women working as private investigators for a mysterious benefactor, whose missions often took them into mysterious, dangerous, and tropical situations. “And we,” wrote feminist film critic Molly Haskell in The New York Times, “who were doing the agitating and analyzing didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.”

Charlie’s Angels became the cornerstone of an entertainment phenomenon (disagreeably) known as “Jiggle TV,” a spectrum of shows, including Wonder Woman, The Bionic Woman, and The Dukes of Hazard, which ogled the bodies of its female characters, even while emphasizing their powers and abilities. Like many of these programs, Charlie’s Angels was, in Haskell’s words, “an artifact of its time, perched precariously on the borderline between snickering sexism and feminism-lite”—or “a site,” in the words of scholar Elana Levine, “for the negotiation of the relationship between the newly visible feminism of the women’s liberation movement and the conventional sex symbol femininity produced by Hollywood.” Viewing Charlie’s Angels as an “artifact,” or better yet, as a “negotiation” between established, regressive values and burgeoning progressive ones, observes that our culture has been on a track to leave such retrograde perspectives behind, and that Charlie’s Angels was just one in a chain of handoffs between the old world order, and the new.

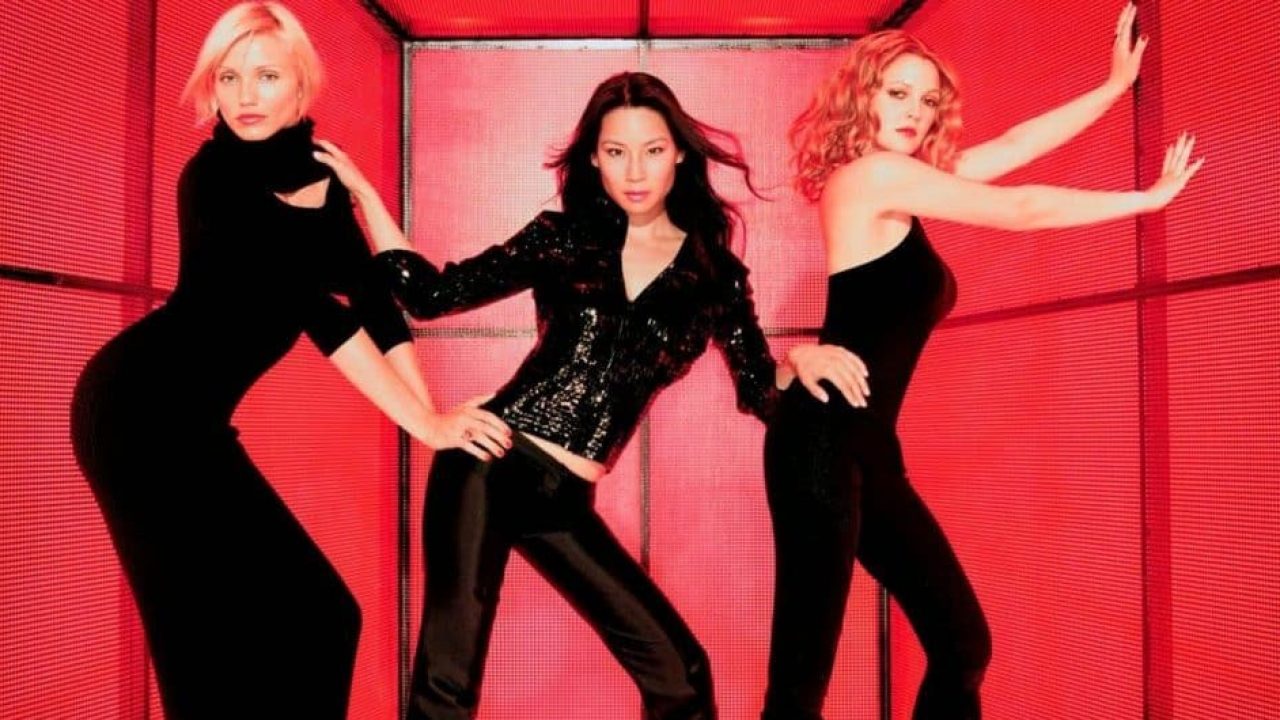

This baton-passing happened rather directly; since the 70s, there have been several reboots of the franchise that have sought to update the story to outfit the changing zeitgeist—most notably a film made in 2000 and starring Drew Barrymore, Cameron Diaz, and Lucy Liu as the three agents, as well as a sequel, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, made three years later. Then, in 2011, ABC produced a new television series reboot starring Minka Kelly, Rachael Taylor, and Annie Ilonzeh, which turned the characters into reformed criminals, and ran for one season. And, most recently, in 2019, the actress and producer Elizabeth Banks wrote and directed a new iteration, starring Kristen Stewart, Naomi Scott, and Ella Balinska.

The guiding plot of Charlie’s Angels is fairly simple: three beautiful female agents are employed as private eyes/agents by a rich man named Charles Townshend (who is never seen, and only contacts his employees via speakerphone). He has an assistant, a nothing-special man named John Bosley, who serves as the Angels’ handler on the ground. They glamorously save the day time and time again, and Charlie is proud of them. That’s it—that’s the whole thing. The 2000 version, a shiny, colorful, loud collaboration between produced/star Barrymore and director McG, intended to re-kickstart the franchise as a girl-power story for a new generation, while also remaining sugary, fun, full of innuendo, and stereotypically feminine. It’s a strange film to behold—watching the women elaborately destroy male bad-guys through intense martial-arts abilities and then wantonly lick the upholstery of racing cars to distract hapless male pawns, sets up a jarring and sometimes confusing dynamic that collocates superior skill with superficial qualities. As Ashley Spenser writes of the adaptation’s awkward existence, “Charlie’s Angels arrived right in the throes of third-wave feminism, which encouraged women to embrace their sexuality and traditionally feminine traits as a means to reclaim their power… Showing women saving the day while still balancing in heels and seducing onlookers was, for many at the time, the height of progress.” She adds, reminding us all what 2000 was like: “These were the days of ‘Oops!…I Did It Again.’”

It’s worth noting that all of the franchise’s iterations have been clear about the apparent usefulness of being an extremely attractive woman. The original TV series and the millennium adaptations all suggest that simply being both gorgeous and female has the strategic advantages of distraction, manipulation, and downright deceit (and our heroines do all of this in the name of the greater good). Elizabeth Banks’s 2019 version, female-led, arriving in the #MeToo era, and starring Kristen Stewart (whose very presence, given her recent status as an LGBTQ icon, offers a toppling of a male heteronormative order long shouldered by the franchise), has promised to turn the characters into, in the words of a hopeful New York Times article “nobody’s sex objects.” But there are many aspects of the franchise it must chop down, in order to really kick open this new dimension.

* * *

The new film, in its opening scene, features one of the Angels (actually, Kristen Stewart, in a long, blond wig) acting as a sexy “decoy,” on a date with a wealthy chauvinist, entertaining him with a few thoughts about female potential (which he casually counters) and aerial silk acrobatics (which he finds riveting). Here, the angel, whose name is Sabina, says that the advantages of being a woman include, if you’re gorgeous, being underestimated, and if you’re not, being invisible. Both, she says, have huge benefits in her line of work. This seems like a hardened, bare-bones breakdown of gender in society told by someone we know will turn out to be a tough chick, but this worldview, in its attempt to slash the patriarchy, kind of already shows that the patriarchy has won—this dumb argument is situated within a misogynistic framework. Indeed, the point of all the Charlie’s Angels versions is that these women live and work in a man’s world and are so bound by its rules—just look at the grammatical nature of the title, which features a man’s name in the possessive case (whatever else these Angels are, they are “Charlie’s”).

But how woman exist and are seen in society is not treated, at this moment in the film, as a question of cultural relativity—a methodology that isn’t so concerned with entrapping men according to their ingrained ideals will automatically shift the paradigm about female visibility and invisibility to a more productive space. That the film does not do this feels like a missed opportunity, considering it does promise to do new, feminist things. Then again, in this scene, Sabina defends women who choose to be housewives, beats up a bunch of thugs, rips off her flowing wig to reveal a short, punk haircut, and then blows a “peace-out” kind of kiss while standing on the shank of a rising helicopter—triumphantly presenting to the audience a whole kaleidoscope of different ways to be a woman, none of which turn out to exist for heterosexual male pleasure. (Stewart is, it is worth saying, fabulous in this film.) It seems cool, but it’s ultimately over-the-top lip service; a kind of a “you go girl” corporate slogan, rather than a thesis that will show up usefully anywhere else.

Three beautiful women will constantly replace one another in the trio, and that will satisfy its requirements…It’s the women whose consistency does not matter; at Charles Townsend’s private detective agency, only the men have agency.

The most concerning thing about the legacy of Charlie’s Angels, and the aspect with which the newest film has to grapple the most, is its body count, so to speak—rather, the hyper-replaceability of its female leads. The crime fighting squad must be a trinity, but the original series saw a total of six actresses in those roles, replacing one another after various actresses left. The show featured actresses Farrah Fawcett, Jaclyn Smith, Cheryl Ladd, Kate Jackson, Shelley Hack, and Tanya Roberts, as (respectively) Jill, Kelly, Kris, Sabrina, Tiffany, and Julie. Indeed, the millennium reboot, and subsequent ABC TV series, have featured totally different women, different names, different qualities, different backstories in the famous trifecta. The 2000s feature Dylan, Natalie, and Alex. The new ABC show features Eve, Abby, and Kate. And the 2019 version features Sabina, Jane, and Elena. That Charlie’s Angels, an action/espionage franchise, lacks a permanent protagonist with a name, like James Bond or even Maxwell Smart, reinforces how much the show is about aesthetics rather than character. Three beautiful women will constantly replace one another in the trio, and that will satisfy its requirements. Subsequent iterations have also reinforced the oddness of this faceless female carousel; the millennium adaptations notably feature the same actor as the disembodied voice of Charlie—the richly-voiced John Forsythe—as the original TV series. Not only does Charlie nominally stick around, but he’s too important a character to modify at all. The millennium adaptations also inherit John Bosley (with Bill Murray playing him, rather than the 70s show’s David Doyle). It’s the women whose consistency does not matter; at Charles Townsend’s private detective agency, only the men really have agency.

* * *

[Spoilers ahead…]

But the new film is surprisingly aware of this tendency, and elaborates on it. The film seeks to connect the 70s show and the 2000s movies as part of the same legacy: characters stress that the Townshend Agency has been operational for forty years, and has expanded from a small coterie of women to an entire international network. In the new film, there are many “Angels,” many “Bosleys” (the name is explained to have become a rank title in the organization), all over the world. A photo slideshow even shows photographs of three Angels from the 2000s movies. The Angels have not been replaced—their numbers have simply grown. Sabina and Jane, the two Angels who work together in the film, are joined by Elena, a new potential recruit—a whistleblower from a tech company who seeks their help (meaning that the plot of the film literally centers on “inclusion”).

This helps emphasize the new Charlie’s Angels’s overall mission: to make a film that centers around female community, support, and friendship. I do think it genuinely wants to succeed at this. Not only does Sabina, Stewart’s character, excellently queer the traditional Angel archetype, but all three women are given opportunities to develop as characters, and as companions—their triangular (rectangular, if you include their Bosley, Elizabeth Banks herself) love story is the point of the film. In this way, the film is just sort of overwhelmingly about “women.” Women’s feelings. Women’s desires. Women’s day-to-day lives. There are countless shots with little girls noticeably playing in the background, and a charming scene where the Angels interact with a little girl on a ferryboat, before falling asleep on one another in a mushy pyramid (a lovely, trusting, down-to-earth, take on the usual image of the three women, which normally has them crouching or karate-chopping or even just posing together, and which has become the franchise’s alternating logo template). The uptight Jane has to reconcile with a former mentor in Istanbul, who runs a women’s health clinic—they help her acquire supplies, including packs of birth control pills, so that she can look out for women who need help in civilian life. (The film is very into the idea that ‘female heroes and role models’ take many forms.) But again, all of this “women stuff” seems thrown at the viewer. If women are everywhere, the film seems to think, and if the film tells you over and over that women are great, then it’s ultimately feminist. Does it do anything meaningful with all of this? No.

(Though, there is, I might add, a refreshing scene where the Angels all sit down to eat a bunch of cheese—so insignificant a detail that it’s not worth mentioning, perhaps, except that I did find it nice to see a bunch of female action stars in a Charlie’s Angels movie settle in to eat some cheese.)

The film has some bigger feminist ambitions, too—all of which are alternately embodied by the film’s villains, all of whom are men.

The film has some bigger feminist ambitions, too—all of which are alternately, obviously embodied by the film’s villains, all of whom are men. A minor bad guy, Jonny Smith (Chris Pang), turns his male-gazing into some naval-gazing, representing a kind of teachable character, at least a wannabe-ally. A big tech developer (Nat Faxon, excellent) gets what he deserves for years of taking credit for women’s work while also talking down to them. A Mark Zuckerberg-style tycoon guru (Sam Clafin) is revealed to be a shady coward, happy to let women (including the female whistleblower he too has flirted with) down if it means financial success. Surprise, surprise.

But the film’s main villain (it’s a surprise, kind of, so I’ll keep it vague) articulates clearly the legacy that the film sees itself as wrestling with. “I’ve,” he thunders to the Angels in a manner which can’t help but echo perceived attitudes of our own world’s most terrible and exploitative misogynists, “spent the better part of forty years estimating the talents of women.” This villain is revealed, rather than the eponymous Charlie (who we find out is dead and has appointed a successor), to be a kind of mastermind behind the effort to turn women into chess pieces, moveable parts, obedient puppets. It’s the male-focused control in Charlie’s Angels that is reflexively criticized as the problematic part of its entire history. (Is he speaking for the film on the whole? Yes, without meaning to. This film, which is so much ABOUT and BY women, also mobilizes women as a product, ultimately.) Although this isn’t a vanguard take, it’s at least an apt one. And so the new film, if nothing else, succeeds for representing this antique patriarchal system as finally being, well, out-manned. It just forgets to hold the women of the patriarchy accountable, too.