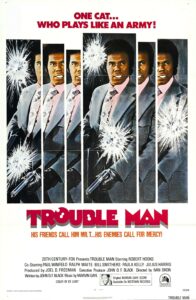

Although the word “Blaxploitation” has become an acceptable one to describe African-American films released from the early-to-late 1970s, many of the actors and directors never liked the term. Still, that was the era when any movie with more melanin was tossed on the Blaxploitation pile. Recently watching a ReelBlack interview with the actor/director Ivan Dixon, whose directorial debut Trouble Man celebrates its 50th anniversary this month, he referred to the film as an “action/adventure” before sarcastically using the dreaded term. In the film Robert Hooks plays Mr. T, a neighborhood fixer in South Central, Los Angeles who is also a private detective. Like Phillip Marlowe and Sam Spade before him, he knows how to kick ass, blast a sucker with his gat and romance the ladies.

More neo-noir than usually noted, Trouble Man reminds me of the 1950s/60s PI films rather than Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) or Slaughter (1972). Los Angeles native and mystery scribe Gary Phillips says of Trouble Man,” I saw the movie at the Baldwin Hills Theater, down the road from where Mr. T had his pad. He was a troubleshooter, neighborhood fixer, pool shark and private eye—a dude who navigates the various enclaves of this vast sprawl as well as knowing how to wheel and deal in these areas.”

Still, if it wasn’t for the success of those aforementioned grindhouse classics there never would’ve been a Mr. T to come to the rescue of Watts folks fighting against slum lords, bail bondsmen and tricky criminals who’d rob or con their own mothers. Shaft co-writer John D. F. Black, who penned that script with novelist and character creator Ernest Tidyman, was the writer/producer on Trouble Man, hoping to cash-in on the popular film trend he helped launch.

Black began his career in television writing jazz detective Johnny Staccato (starring John Cassavetes, music by Elmer Bernstein) and later wrote scripts for The Untouchables, Star Trek (where he was also a producer), Mannix and Hawaii Five-O. Joining forces with Shaft co-producer Joel D. Freeman, they formed JDF/B Productions, and created Trouble Man as a property they could control. Apparently that power only went so far with 20th Century Fox, who bought the script. The studio hired the star, director and soundtrack composer Marvin Gaye. Thankfully for Black, there were no changes to the script.

Phillips, who is a writer on Snowfall and recently edited South Central Noir (Akashic Noir Series), says, “In Trouble Man, there’s that Shaft vibe transplanted to the West Coast, but I also got a Peter Gunn (a 1950s detective show) impression when Mr. T was meeting his street connects and laying cash on them to get information while he’s dressed in a $300 suits. Gunn too was also framed at least once in his adventures for a murder.”

In 2019 episode of The Projection Booth Podcast, host Mike White revisited Trouble Man, and interviewed John D. F. Black and his wife Mary Black about behind the scenes occurrences including basketball legend Bill Russell auditioning to play Mr. T, director Ivan Dixon not being the nicest guy (though, Mrs. Black says he mellowed with age), how MGM (the studio that gave us Shaft) wanted to buy the treatment, but not the production team, and the alleged shady accounting of 20th Century Fox that led to the creators making no money from the project.

The primary star of Trouble Man was Robert Hooks, an actor whose work I knew primarily from the groundbreaking police drama N.Y.P.D. that ran on ABC from 1967 to 1969. Shot in New York City, the show featured young theater actors Al Pacino, James Earl Jones, Jill Clayburgh and John Cazale in guest roles. Hooks too had come out of the theater world, and was the co-founder of the Negro Ensemble Company. After N.Y.P.D. was cancelled, Hooks made guest appearances on Then Came Bronson, The Bold Ones: The New Doctors and The Man and the City starring Anthony Quinn. In 1971 he was offered Trouble Man, which was to be directed by his friend and fellow actor Ivan Dixon.

Harlem born and raised Dixon began acting in college and appeared as the African exchange student Asagai in both the stage production (1959) and motion picture (1961) A Raisin in the Sun. Dixon was the star of the brilliant Black-themed Twilight Zone episode The Big Tall Wish in April, 1960. Written by series creator Rod Serling, Dixon played aging boxer Bolie, whose loser luck turns around after his neighbor’s son wishes him to be a winner.

Four years later Dixon got the part as Duff Anderson, a part that Robert Hooks also went out for, in the masterful Nothing But a Man playing opposite Abby Lincoln, Yaphet Kotto, Gloria Foster and Julius Harris, who was wonderful as his drunken daddy. The following year Dixon was cast in the bizarre CBS series Hogan’s Heroes, which ran from 1965 to 1971. His friend, writer Richard Powell, was instrumental in getting Dixon hired to play radio operator Sgt. James Kinchloe on the Nazi P.O.W. comedy.

Dixon told ReelBlack owner Michael J. Dennis in 2006 that he’d wanted to direct since the sixties, but being married with four kids prevented him from going to film school. Instead he learned what he could on various sets by asking questions of cameramen and directors. According to film historian Spencer Moon, “Hogan’s Heroes became his graduate school in directing. He was on the set everyday for five seasons…He talked with the editor and got to edit some film. He talked with the cameraman Gordon Avil, who gave him his personal time on the weekends when he found out that Dixon really wanted to learn about directing.” Dixon stayed on Hogan’s Heroes until 1970, quitting a year before the show was cancelled.

That year, his friend Bill Cosby was given his first solo sitcom and allowed Dixon to hang-out on set before he earned the star’s confidence to direct an episode. In 1971, he was also hired to direct The Bill Cosby Special. Although Dixon wasn’t very impressed with his own efforts on that production, a few months later he was on the set of Trouble Man. Though Robert Hooks was the lead, the picture featured cool co-stars Paula Kelly (Cleo), Paul Winfield (Chalky), Ralph Waite (Pete) and Julius Harris as Big, the iceberg cool O.G.

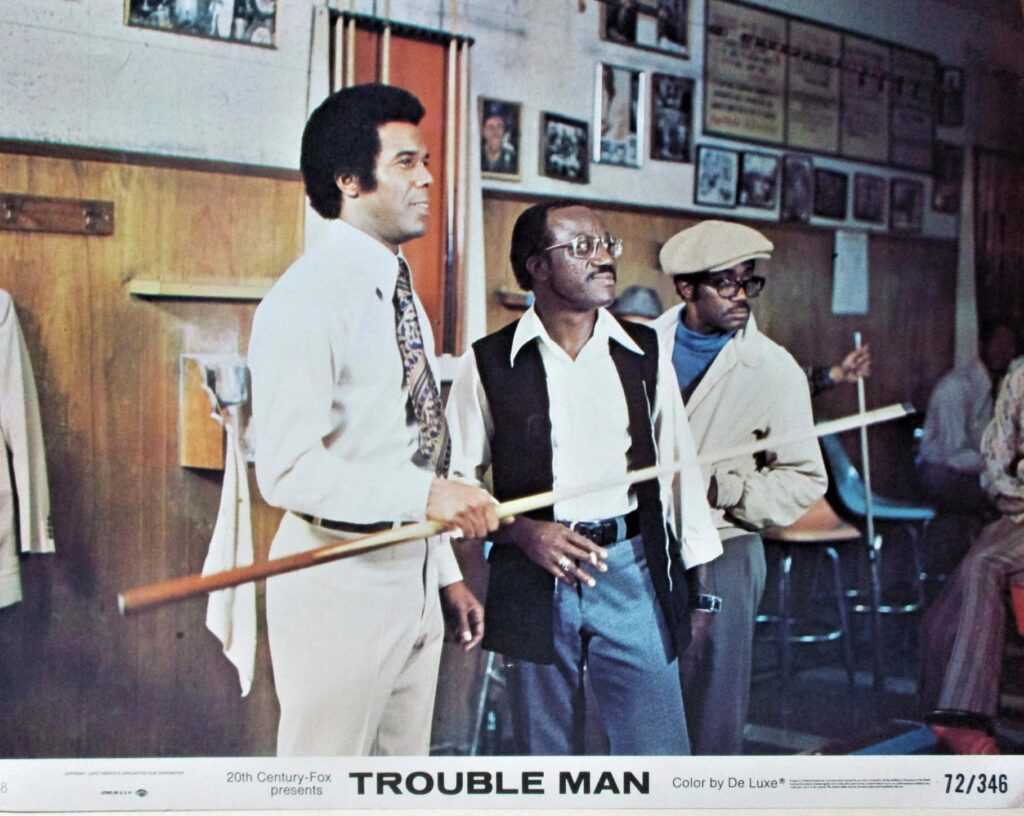

The plot revolves around Chalky and Pete, two low-level thugs, attempting to take over Big’s piece of the illegal action while also eliminating the slick as oil private eye. T’s office is in the back of the neighborhood pool hall that he owns, but was run by his homeboy Jimmy (Bill Henderson); he and Cleo seemed to be the only people T could trust.

L.A. resident Phillips recalls being excited seeing his community on screen. “Jimmy’s pool hall, where Mr. T has his office, was on Western Avenue in South Central,” he says. “In the opening segments of the film there’s a shot when they come out of the pool hall, and you can see the original Fatburger stand across the street. A few years later, just down the block from those locations, would be the Coalition Against Police Abuse (CAPA) office. Organizing on that issue was my baptism of fire as a community activist. There are other degrees of separation for me in the film: Queen of Angels hospital gets name checked and I was born there and in the closing scene, the cute police lady working in Property and Records is my cousin, Tracy Reed.”

Trouble Man was made quickly and on a shoestring budget. When it was released it wasn’t treated kindly by most critics, with the New York Times calling it “horrible” and, six years later author Harry Medved included it in The Fifty Worst Films of All Time (1978). Medved’s list also included Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1979) and Valley of the Dolls (1967), so, obviously he didn’t know jack about movies.

Crime writer Wallace Stroby, who is more a fan of the soundtrack than the film, says, “One of the things I do like about the movie is that T (whatever his real name is) moves through a distinct milieu—the bars, pool halls and boxing gyms of downtown Los Angeles. T is a loner, but he’s also part of a community. He knows everybody and everybody knows him. Hooks is a real presence here, even if he does seem to be channeling Clint Eastwood at times. A pioneer in African-American theater, Hooks deserved more of a film career than he had, but, hopefully, the paycheck from Trouble Man helped finance productions at New York’s Negro Ensemble Company.”

***

While I count Trouble Man among my favorites of the Blaxploitation era, that wasn’t always the case. Unlike Slaughter or The Mack, I didn’t see Trouble Man at any of the Harlem theatres (The Tapia, The Roosevelt or The Loew’s Victoria) I frequented back then. I wouldn’t view it until I bought a bootleg on 125th Street in the late ‘80s, and I wasn’t impressed. I’m guessing I was in a bad mood that day, because when I watched Trouble Man again a few years I thoroughly enjoyed it, though I understood why it failed at the box-office. Mr. T was cool, but there was conservatism to the character that made him a more upright citizen than most of the cinematic soul brothers: T liked the ladies, but we never saw him ball nor was there any nudity; unlike Youngblood Priest (Super Fly), he wasn’t taking hits of blow every other scene; also, T wore suits and ties as opposed to the flamboyant treads that could’ve been in a Flagg Brothers catalogue.

If I had to pick a Blaxploitation hero most likely to become a Black Republican, I’d vote for Mr. T. “I’ve always loved what I thought was the director’s attempt to make Robert Hook’s character more sophisticated than those in other black films at the time,” my friend Bruce Mack recalls. “Hook brought that confidence.” While it was strange seeing the father from The Waltons (Ralph Waite) playing a thug who thinks he’s bad enough to talk shit to T before the final showdown, my favorite co-stars in Trouble Man were badass Julius Harris as Big and T’s lady Cleo, played by the always stunning Paula Kelly.

Though Pam Grier gets more ink, Kelly made just as many 1970s flicks, but hers tended to be a lot weirder including, Top of the Heap (1972) and The Spook Who Sat by the Door. The latter film was also directed by Ivan Dixon and released the following year. My introduction to Kelly was seeing her in the musical Sweet Charity (1969) directed by Bob Fosse, where she turned out the “Hey Big Spender” number. She was also in the cult film Soylent Green (1973) and the Richard Pryor bio-pic Jo Jo Dancer Your Life Is Calling (1986). “Never over playing her role, fine-dance-her-ass-off Paula Kelly is dope as ever,” says Mack, echoing my sentiments. “I had a crush on her, but she would always appear in anything on TV or film just for a short moment. It was always like a tease seeing her; for me, as a young boy, she was everything.”

The other star of Trouble Man is superb soundtrack by Marvin Gaye with its soulful theme song and a moody/jazzy/funky score that plays throughout. Gaye recorded the music twice, once for the movie and again for the album version that serves as an experimental follow-up to his 1971 masterwork What’s Going On. “I was shocked at how little music was actually used, how deep in the background it was, and how unfinished it sounded in comparison to the album, which was completed later,” says Gaye aficionado and musician Daniel Zelonky aka Low Res. “If they had had more time, allowing them access to the finished album tracks, and if they’d featured them more prominently, it might have really helped the film.”

While I had an immediate love for the soundtracks of Shaft (Isaac Hayes) and Super Fly (Curtis Mayfield) when I was a boy, Trouble Man had a grown man scotch and cigar vibe that I couldn’t grasp when I was nine. It took years for me to embrace and appreciate the post-bop/electric fusion that Gaye served cool and hot. The music was simultaneously lush and minimalistic, and Gaye produced the entire project while also contributing vocals, drums, Minimoog synthesizer, keyboards and piano. There were also contributions from Trevor Lawrence on sax, and he was the only musician credited on the album’s original release. The title track features drummer Earl Palmer and pianist Larry Mizell while various arrangers including J.J. Johnson, Gene Page and Gene Oehier contribute to the album.

Stroby didn’t share my youthful aversion to the mature music; he has owned the Trouble Man tape since he was thirteen. “Even as a young teen, I was listening to a lot of soundtracks, and because of its poster I bought the 8-track. Of all the film scores from that era, that’s the one I’ve continually listened to the most over the years. For me, the score is a separate entity from the film, and stands on its own. It’s all of a piece, a 40-minute suite, jazzier than most of the funk-driven soundtracks of the time, but still dramatic and evocative.” Stroby even name checked the film in his 2010 novel Gone ‘Til November.

“I come up hard baby, but now I’m cool,” Gaye sang on the title track. “I didn’t make it sugar, playin’ by the rules/I come up hard baby, but now I’m fine I’m checkin’ trouble sugar, movin’ down the line.” Over the years the title track has been remade by Neneh Cherry, George Duke, Chico DeBarge and Joni Mitchell. “I had this song on an album and I kept the needle on this track—playing it over and over,” Mitchell said in 2005. “It was so influential to my music and my singing. It excites me from the downbeat—the way the drums roll in – the suspense – the approaching storm of it.”

In a 1976 interview Marvin Gaye told interviewer Paul Gambaccini from BBC Radio One, “The Trouble Man film score was one of my loveliest projects, and one of the great sleepers of our time. I’ll probably be dead and gone before I get the probable acclaim from the Trouble Man album, the musical track, that I feel I should get. If somebody took that album and did a symphony on it, I think it would be quite interesting. I enjoyed that job immensely; I enjoyed writing a film score. I’d love to do more. I think it’s probably some of my finer work.” Gaye also pointed out that he was listening to a lot of George Gershwin while working on Trouble Man.

In celebration of the soundtrack’s 50th anniversary, Low Res remade the complete album as Marvin Gaye’s Trouble Man (S’plat Records) a dazzling project I imagine the Motown soul man would’ve loved. Having recreated and conducted the entire film score live with a 36 piece orchestra at Voouit, a beautiful classical venue in Gent, Belgium, the final product is a brilliant tribute. “After auditioning all the players, I had to transcribe the parts by ear,” Res explains, “and the original record is not exactly crystal clear—in fact it’s pretty murky, particularly the orchestral sections. Then, over nine days of rehearsals, I went home every night and made corrections and modifications, taking certain liberties to bring something new to it. For example, the first section of ‘Poor Abbey Walsh,’ which is harmonically related to the original, is a totally different arrangement. This was in Belgium, where funk is not the native language, so I had to ride the rhythm section to get the feel right. Fortunately, the musicians were generally very skilled and helpful, and somehow it all came together by the time of the performance.

“I realized after reviewing the recordings, that I needed to do what Marvin had done, which is to overdub additional instrumentation after the fact. On several songs I added additional synthesizer, piano and guitar. At that point it began to be worthy of the work, I hope.” Indeed, from the opening chords and greasy sax on “Main Theme from Trouble Man,” it’s obvious that Res knows what he’s doing.

“Trouble Man was completely its own world,” Res says. “It was conceived as orchestral funk — it’s built into the DNA of the piece. It’s not just a batch of Marvin Gaye songs that some Hollywood cats decorated with orchestral elements. Also, there is so much jazz influence and harmony in there. I think the only piece that really sounds typical of Blaxploitation is the second section of ‘The Break In.’ I love the conventional Blaxploitation soundtracks as well, but the dark, jazz-infused and epic character conveyed in Marvin’s work is something unlike any of the others.”

Much of the album’s musical moodiness can be traced to Gaye’s use of the MiniMoog, an instrument that became available in 1970 and was a gift from his friend and Motown label-mate Stevie Wonder. “The Moog gave Gaye’s soundscape a sense of modernism,” says keyboardist/composer Bruce Mack, founding member of the Black Rock coalition and Burnt Sugar the Arkestra Chamber “This is ironic in that his production already had a more modern sound than the rest other Motown artists. I think he pushed the limits of arrangements on What’s Going On, and my feeling was that the Moog provided a tangible route to ‘what comes next. The Moog sort of catapults him and the character Mr. T into a new age. The Moog makes Gaye the alter ego and sits him on the shoulder of “T” throughout the score.”

The heavy soul of “T Plays It Cool” is Mack’s favorite track. “It’s as funky as all simplistic funkdom can be,” he says. “In terms of groove and infectiousness, it is on par with James Brown’s ‘Funky Drummer.’ The Moog and drum-play combined gives it a sort of ‘intergalactic’ feel, made me feel like I already know what being in outer-space felt like, separating it from what Clyde Stubblefield’s work (respectfully) which grounds you. Knowing that Gaye was a drummer earlier in his career and you get to hear him play this tasty funk was super exciting. Hearing that exquisite vocalist create this type of sonic environment kicked down doors for me as I listened more and grew older with this album; it’s still a favorite.”

Fifty-years after the release of Trouble Man, many of the creative folks behind the film and soundtrack (Ivan Dixon, Marvin Gaye, Paula Kelly) are long buried, but the endearing artistic legacy they left behind with that one project is eternal.