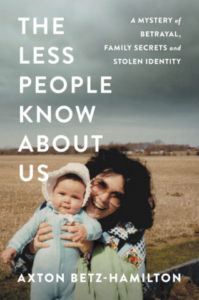

In the introduction of debut author Axton Betz-Hamilton’s memoir The Less People Know About Us: A Mystery of Betrayal, Family Secrets and Stolen Identity, a college-age Betz-Hamilton receives a credit report in the mail that reveals a shocking secret: despite never having had a credit card, her credit score is 380. Yet somehow, the first line of credit under her name had been opened when she was eleven. Her confusion morphs into horror as she realizes her report also contains several bank and collection agency notices. Betz-Hamilton’s revelation that her identity has been stolen comes after a childhood of paranoia: her parents’ identities had also been stolen years before. The police never found the culprit.

Identity theft and fraud lay at the heart of Betz-Hamilton’s memoir. It’s a true crime story that bleeds into every moment of her childhood and adulthood, one with a slow burn to a shocking conclusion. There’s also a larger question she poses: how can someone form an identity in adulthood when someone has stolen theirs before they even knew what a credit score was? And as a reader, I found it impossible to avoid asking myself: why aren’t more people sharing their own identity theft stories in the era of scammers and true crime?

Identity theft and fraud have become far more common over the past few decades, but the abstract nature of stealing someone’s identity is tricky to portray in writing. Frauds and scams, at times, lend themselves more readily to true crime, since by their very definition they involve drama and tension—a thief steals or forges something to get what they want.

One would think that identity theft as a narrative would swiftly gain popularity in the true crime boom over the past five years. Especially since true crime’s popularity as a genre has also intersected with the 2016 election and Trump’s inauguration, when the subject of the successful, renegade con man “sticking it to the system” while defrauding American voters seemed to explode all over the media. If a fraudulent businessman could win the presidency, what other scams have we as Americans fallen for?

In the 2019 essay collection Trick Mirror, New Yorker staff writer Jia Tolentino examines the many forms of self-delusion Americans in particular have fallen into over the past decade. The appeal of the scammer story in the late 2010’s is broken down succinctly by Jia Tolentino’s in her essay “The Story of a Generation in Seven Scams:” “Stories about blatant con artists allow us to have the scam both ways: we get the pleasure of seeing the scammer exposed and humiliated, but also the retrospective, vicarious thrill of watching the scammer take people for a ride.” Stories of fraud, especially ones that are true, while not as gory or disturbing as violent crime stories, allow for drama and judgement from a safe distance. The reader can assure themselves they’d never be conned, or if they were to pull off a con, that they’d never get caught.

But Betz-Hamilton’s story doesn’t allow for an easy, neatly solved fraud narrative. Identity theft followed her family like a specter for the majority of her life. They all lived within a cult-like sphere of secrecy for fear of having more taken from them than just their credit scores. They removed themselves from the lives of their family members, friends, and the surrounding rural community.

Betz-Hamilton is now one of the foremost experts on identity theft in the United States, and wrote her dissertation on the effect of identity theft in childhood. Her entire life still revolves around the crime that happened to her. The trauma of learning that her identity was taken by someone close to her seeps into every part of her life. In lieu of a bloody, violent event, the harm that is done against her is inflicted slowly and carefully over time. The quest to solve the mystery of who stole her identity is a slow and painful burn, one that’s difficult to translate into an archetypal shape of a story where the criminal is brought to justice.

It is this difficulty defining the shape of identity theft that makes it so difficult to write about. There aren’t many familial identity theft memoirs where the victim spells out how the theft happened and how it effected her life. In addition to concerning itself with a true crime story, Betz-Hamilton’s memoir is also about growing up in Midwestern farm country. One recent example, Christina McDowell’s memoir After Perfect: A Daughter’s Memoir, explores the disintegration of her family after her father’s fraud conviction. She delves into the family’s fall from privileged grace, but she’s still able to keep her identity intact. Betz-Hamilton and her family’s story is all-encompassing. The damage cannot be unraveled as easily as McDowell’s, where it is clear from the start who in the family has committed the crime. In addition, the fraud he committed was at the workplace—he didn’t steal the identities of his own family members. And as more and more of our lives have become digital, it is likely that more memoirs like Betz-Hamilton’s will emerge that engage with the violation of having one’s identity stolen, especially identity theft without families.

* * *

Shame, secrecy, and the invisible nature of surviving identity theft makes sharing those crimes more difficult for victims. If your financial identity has been stolen, how much of the rest of your identity—physical, emotional, mental, spiritual—are you willing to sign over in book form? As Betz-Hamilton narrates in her memoir, the aftermath of the crime is a never-ending trail of paperwork. Rather than a detective collecting forensic evidence, her investigation meant learning to decode the language of banks, loans, collection agencies, and laws surrounding fraud. The uphill battle is one of bureaucracy. And bureaucracy rarely makes for compelling crime literature.

Rather than a detective collecting forensic evidence, her investigation meant learning to decode the language of banks, loans, collection agencies, and laws surrounding fraud.When searching for identity theft in contemporary literature, it is far easier to find fraudulent memoirs than memoirs about having been defrauded. In 1995, Binjamin Wilkormirski (real name Bruno Dössekker) published a memoir, Fragments: Memories of a Wartime Childhood, in which he claimed to be a Holocaust survivor. It wasn’t until 1998 when Swiss journalist and writer Daniel Ganzfried debunked his story that it was revealed the entire memoir was fictional. James Frey, perhaps the most infamous imposter memoir writers, rose to prominence with his memoir of addiction entitled A Million Little Pieces in 2003. When it was revealed by The Smoking Gun that much of the book was factually inaccurate, his publishers admitted they hadn’t fact-checked his story. Both writers had stretched the truth of their lives, or lied outright, to take on the identity of someone else, someone who perhaps they thought might be more thrilling or sympathetic to read about. The victims of this specific type of fraud are the readers, who believed the truth of these stories as fact. Both male narrators’ identities and the stories that readers were sold on weren’t factually accurate despite the books originally being designated as “memoir.”

When studying popular true crime stories featuring stolen identity, it’s clear that we celebrate the male scammer far more than the female scammer. Con men are depicted as almost noble, cheating the system to get ahead. Look no further than the cheeky tone of the movie Catch Me If You Can, where the viewer cheers for the handsome, notorious check forger and imposter Frank Abagnale. Even Mrs. Doubtfire, the classic movie based off of a novel of the same name, is one with identity deception is at its core. The protagonist dresses in drag and creates a fake persona in order to visit his children after a divorce. Though the movie is presented as a fun comedy of errors, successful in no small part thanks to Robin Williams’ brilliant acting, it’s still one of identity theft as a means in which to get what a man wants. His scheme to visit his children is something to celebrate rather than an insidious crime done over and over again, violating his ex-wife’s wishes.

Women who try to game the system illegally, on the other hand, don’t typically get as much sympathy. In Michelle Dean’s blockbuster Buzzfeed longform investigation, “Dee Dee Wanted Her Daughter To Be Sick, Gypsy Rose Wanted Her Mom Murdered,” Dean spells out the bizarre, horrendous murder of Dee Dee Blanchard by her daughter Gypsy Rose and Gypsy Rose’s boyfriend Nicholas Godejean, whom she had abused for years via Munchausen’s-by-Proxy. In addition to convincing everyone that her daughter was gravely ill, from doctors to neighbors to family to Gypsy Rose herself, she committed identity theft and fraud, check forgery, and a host of other financial crimes to gain sympathy and support. Dean’s reporting is incredibly humanizing towards both women, and the revenge tale of daughter killing mother into find freedom reads like a contemporary Grimm’s fairy tale. But the messiness of their respective crimes is difficult to discern given the complicating factors involved. Neither seems fully sympathetic when they are deceiving others for help. Rather than merely stealing money or identity, they also violated the goodwill of loved ones and strangers. This sensationalized the story further and added to its horror in the public eye. Stealing money is one thing, but stealing an identity as a sick parent and sick child while betraying a community’s trust, is another. Knowledge of this level of sustained abuse almost makes us forgive Gypsy Rose for her actions, but not quite.

* * *

In Betz-Hamilton’s memoir, evidence slowly mounts that the identity thief is Betz-Hamilton’s own mother. Betz-Hamilton’s mother was miserable about her circumstances living on her family’s property as she grieved the loss of her father. She stole the identities of those closest to her to buy jewelry, property, and more, all of which she kept secret from the author and her father. Though the reasons why she committed these crimes will always remain somewhat hazy because Betz-Hamilton and her father only put the pieces together after she had passed away, the more terrifying part of the identity theft is the amount of deception it took to pull off.

The theft is beyond a credit score or reputation—it’s the corruption of memories and the violation of familial bonds.By robbing Betz-Hamilton of her financial identity, her mother also robbed her daughter of the ability to trust in cherished childhood moments, “Good memories immediately segued into speculation about her motives…I now wondered if mother-daughter time was a ploy, to keep me under her thumb and off her tail.” The theft is beyond a credit score or reputation—it’s the corruption of memories and the violation of familial bonds. Betz-Hamilton’s entire life, and her entire memoir, become evidence that she must recast and retell to grasp some version of the truth. After this discovery, all pleasure and nostalgia for her mother are erased, “I could not longer answer personal questions about her or us with any kind of accuracy. I had become an unreliable narrator about my own life.” The idea of mothering while stealing her child’s identity simultaneously is impossible to reconcile, which makes for an upsetting yet compelling literary tension. As Dean also demonstrates when writing about the Blanchards, the mother who comforts and provides support for her daughter while simultaneously deceiving her child, her family, and her community is a far more horrific crime than merely stealing an identity.

Unlike Wilkormiski and Frey, Betz-Hamilton’s account is literary yet honest in its amorphous uncertainty. And that kind of honesty is vital in memoir but hard to come by in accounts of identity theft. We feel sympathy for Betz-Hamilton as well as fascination—what does one’s familial identity look like post-identity theft? That trauma is tougher to articulate because the wound is only apparent in a credit score and fractured family memories, not in anything we can see, touch, or photograph.

It makes perfect sense that Betz-Hamilton would use memoir as an opportunity to trace her life and the crime that has defined it—in many ways, aside from her initial credit score and the piles of paperwork, her life story is the best evidence she has that the crime existed at all. The identity she’s built for herself in the wake of disaster is a form of justice in her mother’s absence. In addition to her scholarly work, creating a work of literature breathes life and credibility into the violating nature of identity theft. It allows us space to question who we give our sympathy to in an era of glorified scammer stories, as well as space for victims to present a new, if fractured, identity to the reader.