How do couples show their love? Some do it with flowers, because nothing screams romance like a handful of dying vegetation. Others send cute notes to one another, especially at this time of year. And in noir world, a lucky few get the chance to die together in a hail of high-velocity bullets.

Yes, romance in noir almost always starts out well, only to descend into death and despair (if you want to get truly pretentious and Greek about it, the characters’ eros, or love, just can’t overcome their thanatos, or death impulse). With that in mind, and in celebration of Valentine’s Day, here are seven films about lovestruck couples who truly go the distance—sometimes right into a police roadblock.

Double Indemnity (1944)

Boy (Fred MacMurray as Walter Neff, smarmy) meets girl (Barbara Stanwyck as Phyllis Dietrichson, ice-cold). Boy helps girl kill her husband and dispose of the body in a way that looks like an accident, so they can score an extra-large helping of insurance money (the “double indemnity” of the title). Boy and girl try to escape the subsequent investigation’s ever-tightening noose, even as boy begins to suspect that girl is a murder-crazed lunatic. Boy and girl turn on each other, adding to the body count. It’s the perfect Valentine’s Day movie—right before you deliver the breakup speech.

Out of the Past (1947)

The quintessential noir, with not one but two doomed romances. There’s the “typical” noir affair between private investigator Jeff (Robert Mitchum) and femme fatale Kathie (Jane Greer), filled with growing suspicion, murder, and double-crosses. Jeff tries to escape by starting a new life as a gas-station owner in a small town—but when Kathie re-appears, it destroys the conventional relationship he’d been trying to build with Ann Miller, a local woman with none of Kathie’s darkness.

Everything goes wrong with clockwork precision, of course, which is one of the reasons why Out of the Past is widely recognized as a classic (that, and the stunning acting and cinematography). Kathie is evil, but she’s also so alluring that Jeff can’t help but follow her to his doom. “I never told you I was anything but what I am,” Katie tells him. “You just wanted to imagine I was.” It becomes a perfect epitaph for both of them.

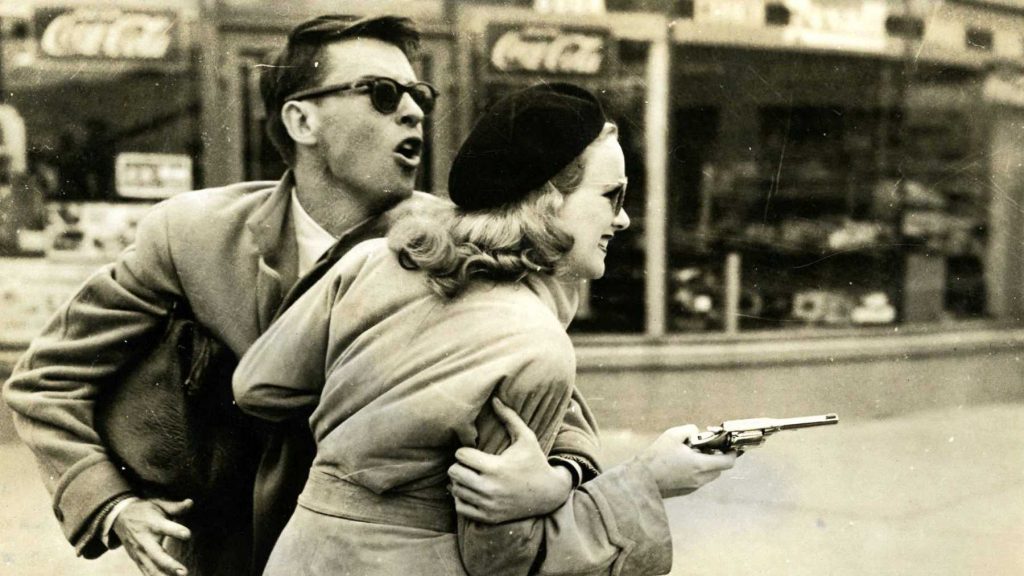

Gun Crazy (1950)

At one point, Gun Crazy had the alternative (and deeply misogynistic) title Deadly Is the Female. The script, which follows a husband and wife as they rob and kill their way across the country, was secretly penned by Dalton Trumbo, who was blacklisted at the time as a member of the so-called Hollywood Ten. (Screenwriter Millard Kaufman served as Trumbo’s “front” so the latter could continue working. “We discussed it and we believed it was rotten that a man couldn’t write under his own name,” Kaufman would later say.)

Gun Crazy tries to distill the femme fatale to her purest essence. Annie Laurie Starr (played by Peggy Cummins) is willing to do whatever it takes to score enough cash to retire to a life of luxury. Her husband, Bart Tare (John Dall) is more reluctant to engage in a cross-state crime spree, but ultimately can’t stay away from his murderous love. “We go together, Laurie,” he says at one point. “I don’t know why. Maybe like guns and ammunition go together.” It’s not exactly a sentiment for a Hallmark card, but it works for noir.

Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967) is the ultimate act of cinematic transformation: It took a pair of dirty, doomed bank robbers—barely more than kids when they were ambushed and gunned down by law enforcement in 1934—and transformed them into extremely photogenic, almost relentlessly suave icons of American rebellion. At least, that’s the hot take; the film has far more layers than you might remember, if you haven’t seen it in a decade or two (or if you’ve never seen it at all, which is something you need to fix).

As portrayed by Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker not only look good—they know they look good. But at crucial moments throughout the film, a far uglier reality intrudes. Friends, family, and innocent bystanders die messily; Clyde and Bonnie panic at the idea that there’s no way out. They don’t look quite so photogenic once the law has its way with them.

What the cinematic Bonnie and Clyde share with their historical inspiration is an all-consuming love, however doomed. One wonders how the real-life robbers, who were intensely aware of their media image when they were alive, would have regarded the 1967 film. They probably would have enjoyed being played by Beatty and Dunaway… and lamented the lack of a happy ending.

Badlands (1973)

Before he was famous, Terrence Malick was friends with Arthur Penn; the two were brought together by Malick’s first wife, who worked as Penn’s assistant. Inspired by Bonnie and Clyde, Malick wrote and directed Badlands, which features a young couple (Kit, played by Martin Sheen, and Holly, played by Sissy Spacek) who become fugitives after Kit shoots Holly’s father and burns his house down. They flee into the Montana badlands and, like the cinematic Bonnie and Clyde before them, try to exist on their own terms. But society, like gravity, has a way of crushing everyone who tries to defy it.

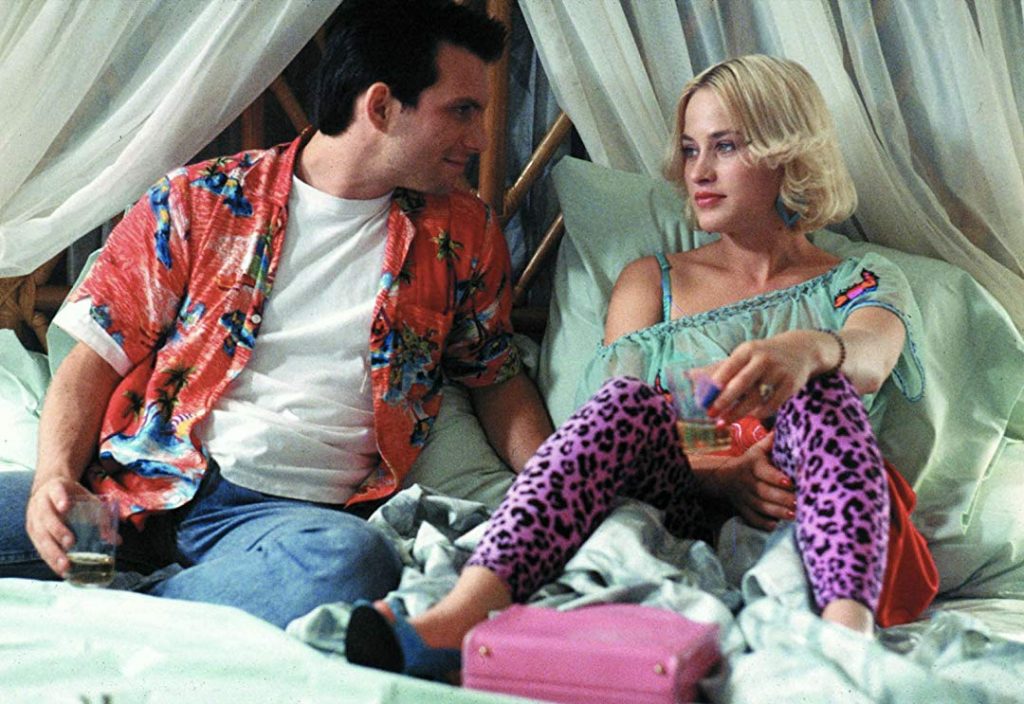

True Romance (1993)

Quentin Tarantino wrote, and Tony Scott directed, this update of the Bonnie and Clyde story. In this iteration, call girl meets boy; boy guns down call girl’s pimp; happy couple escapes to Los Angeles with the pimp’s cocaine. The final film varies considerably from Tarantino’s original script, which (like Pulp Fiction) is non-linear, and ends with one of the main characters dying. Indeed, of all the lovers-on-the-run films throughout film-noir history, True Romance no doubt ends the happiest—so if you’re feeling optimistic about the nature of love on Valentine’s Day, perhaps this is the film to watch.

Savages (2012)

Oliver Stone’s adaptation of Don Winslow’s novel is perhaps the odd one out on this list, if only because it involves, in place of a couple, a threesome. Chon (Taylor Kitsch) and Ben (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) are highly successful weed growers in a polyamorous relationship with Ophelia (Blake Lively). Ben, the botanist, grows prime weed, while Chon, a veteran of Afghanistan, runs security. Everything is going great until a Mexican cartel decides it wants a “partnership” with the duo, and they kidnap Ophelia in order to ensure compliance.

Mucho gunfire, as you might expect, ensues. And that’s where things get weird (predictably so, considering it’s a Stone neo-noir). Whereas Winslow’s source novel ends in gunfire and tragedy, Stone can’t resist trying to staple on a happy ending—even if it involves busting down the fourth wall between characters and audience. But is that “happy ending” real, or a hallucination? It’s impossible to tell, and the overexposed, ultra-hyper film style doesn’t help matters. As a film, Savages is a bit of a mess—but then again, who said romance was supposed to be clean?