There’s a passage by the great Salman Rushdie in his novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet that I’ve long admired and like to revisit every so often. It’s about those select few who are born into the world as inherent non-belongers—societal outcasts who march to the beat of their own drum, or who march to no drum at all—and how we, the presumed upstanding citizenry, secretly admire and wish we could be more like them. I say “presumed” because Rushdie posits that perhaps there are even more of these outcasts than we know—perhaps even we are among them, born with the same inherent proclivities, but we hide among the ranks of the upstanding citizenry because we’ve repressed ourselves as a result of the “powerful system of stigmas and taboos” erected by those who fear transience, uncertainty and change.

The full passage is too long to share in this article (I do recommend you look it up), but here’s the excerpt I think is most meaningful:

“What we forbid ourselves we pay good money to watch, in a playhouse or a movie theater, or to read about between the secret covers of a book. Our libraries, our palaces of entertainment tell the truth. The tramp, the assassin, the rebel, the thief, the mutant, the outcast, the delinquent, the devil, the sinner, the traveler, the gangster, the runner, the mask: if we did not recognize in them our least-fulfilled needs, we would not invent them over and over again, in every place, in every language, in every time.”

I’ve been a graffiti enthusiast for most of my life now. It all started when I was in the 5th grade as I was being driven to school by my mom. There on the side of the 5 Freeway in Santa Ana, California, the letters SYCO were crudely scrawled in big bubble letters at the entrance of our usual onramp. It would be many years before I would come to know that this was referred to as a “throwie” by the graff community, but I admired that throwie for a few brief seconds every day, five days a week, for as long as it stayed up on the wall during that school year. It makes sense that I was drawn to it—this was also the age when I first discovered hip-hop, staying up late at night listening to Power 106 to catch verses by the likes of Warren G, 2Pac and a new rapper named Snoop Doggy Dogg. It was the age when I started wearing boxer shorts so I could sag my pants. The age of suburban pre-teen angst—so full of confused feelings and a desire to seek out an identity foreign to my upbringing. The beginning of the age of rebellion, vanilla as it may have been. And since the adults in my life didn’t like graffiti (I still remember the condemnation of the graffiti writer called CHAKA whose name was up all over the Southland), my admiration of it was a means to distinguish myself from them, even if I didn’t realize it for what it was at the time. So, in elementary school, I began to emulate these freeway calligraphers on the walls of my spiral-bound notebooks—doodling SYCO and other indeterminate letter combinations when the teacher wasn’t looking.

It never evolved beyond those simple schoolbook drawings for me, however. I’ve never been a practitioner of graffiti, nor any sort of graffiti-style art. I don’t have the artistic talent for it, and I was never the type of kid who was willing to engage in vandalism. But I never lost my admiration for it. I always felt close to it as an act of rebellion—for me, my delight in appreciating graffiti was rebellion enough. And to this day, as I snap photos of graffiti around Los Angeles and other world cities I’m lucky enough to visit, the thrill is still very much alive.

Naturally, as I set out to write my first novel, the character that immediately sprang to mind was a graffiti writer. Reflecting back on Rushdie’s passage, I needed to live vicariously through an outcast of my own invention—one of the non-belongers I’d admired since my childhood—an act necessary to fill an unfulfilled need. I needed to feel the thrill of writing graffiti, making my mark on the world against the wishes of the do-gooder citizenry, even if only in words, in fiction, in deeds constructed on the page. It’s not the same as the real thing, of course, and I’m not suggesting that I’ve walked in the shoes of a graffiti writer for having written about them—my acts of graffiti were all safe from harm and free from consequence, not the least bit courageous. But my hope is that I’ve taken my love of graffiti, and my admiration for the men and women who dare to practice the craft, and manifested it in a way that honors them—that demonstrates my appreciation for the constant source of inspiration they’ve given me over the years.

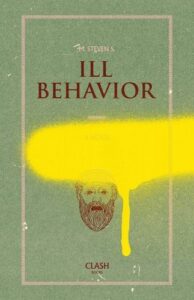

My debut novel, Ill Behavior, was just published by CLASH Books on November 23rd. The story follows a graffiti writer who finds himself wanted for a murder he did not commit, and so he sets out to clear his graffiti name with the help of a childhood friend in the LAPD. Below is an excerpt from a section in which I briefly compare and contrast the nature of outdoor advertising and graffiti. Inspiration certainly flows from Rushdie’s passage—and I hope it adequately pays homage to graffiti writers all around the world.

“But if we are to weigh the ills of the ubiquity of outdoor advertising against the inevitable presence of graffiti in The Big City, it’s incumbent upon us to remember that one group’s motivation is manipulative in nature—intended to alter our purchasing behavior, demanding that we conform and swear allegiance to a particular brand. Whereas the other group’s motivation is expressive in nature—intended to remind us that they are alive and out there, seizing the night and declaring “Damn the Man!” And in the heart of even the most stodgy, straitlaced person, deep down, a small part of them wishes they could join ranks with this second group—perhaps not to tag walls or to vandalize property, but to live as fearlessly and freely.”

Now, if I may, and if only for myself, among Rushdie’s list of non-belongers who we might secretly aspire to be, a list that includes the tramp, the rebel, the thief, the delinquent, I add to it: the vandal.

***