Eugène-François Vidocq (1775-1857) was, at various times in his life, a thief, a puppeteer with a troupe of traveling performers, a soldier, a convict, a cop, a private detective, and, by the end, a bestselling author in his native France. If Vidocq hadn’t existed, to mangle a quote from Voltaire, it would have been necessary to invent him. Indeed, crime-fiction writers of the 19th century found considerable inspiration in his life and work—and their writing, in turn, fueled the genre for more than two centuries.

This is all a very roundabout way of saying that Vidocq, inadvertently, is one of the fathers of the modern detective novel. There’s a little bit of irony in that statement; whereas many fictional detectives are damned by critics as too unrealistic—their memories too sharp, their adventures too outlandish—Vidocq lived an actual life that puts many of his fictional brethren to shame. This was someone who (if you believe his account) not only dressed as a nun to escape a prison hospital, but disappeared so deeply into the disguise that he fooled other nuns.

(“I was then compelled to go to church, and it was no trifling embarrassment for me to make the signs and genuflexions prescribed to a nun,” Vidocq would later write in his memoirs. “Fortunately, the curate’s old female servant was at my side, and I got through very well by imitating her in every particular.” That discomfort is no surprise, considering his reputation as a womanizer. However, his skill at disguise would serve him very well much later on, as a detective.)

And the incident with the nun disguise is only a footnote in a young life that also included privateering, a somewhat-profitable rampage around the battlefields of Europe, and liberal amounts of thievery. Following this early period as a criminal, fugitive, and deserter, Vidocq navigated his thirties with the realization that his criminal past was becoming more and more of a burden. While in prison, he decided to flip sides, feeding information to the Paris police. Freed, he continued his life as an informant; by 1811, he had convinced the authorities to allow him to head up a plainclothes unit, Brigade de la Sûreté, that eventually employed dozens of agents (many of them former criminals like Vidocq). In his memoirs, he took quite a bit of credit for depressing the crime rates in Paris:

“Before my time, strangers and country people looked on Paris as a den of infamy, where it was requisite to keep incessantly on the alert; and where all comers, however guarded and careful, were sure to pay their footing. Since my time, there was no department… in which more crimes, and more horrible crimes, were perpetrated than in the department of the Seine; now there is none in which fewer guilty offenders have remained unknown, or fewer crimes remained unpunished.”

However, Vidocq drew criticism for his tactics, and the Paris police administration (possibly jealous of his success) handed him warnings about his men lurking in brothels and bars. He resigned, briefly launching a career as an entrepreneur (his primary attempt, a paper factory, failed), only to rejoin the Sûreté, then resign a second time in 1832 when the propriety of his men and methods was questioned yet again. The next year, he founded his own detective bureau, Le bureau des renseignements.

Vidocq and his squad of detectives continually found themselves at odds with the “regular” police, which no doubt resented a private company interfering in affairs of crime and punishment. Yet even as Vidocq earned considerable money collecting debts, as well as sparing businessmen from swindlers (he expected to earn a percentage of whatever funds he recovered), he was courting international renown.

The First Celebrity Detective

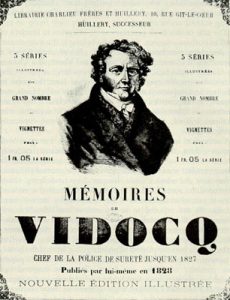

Vidocq made quite a bit of money from his memoirs, which, once published in late 1828 and translated into English, quickly spread his name beyond France. In 1829, at the Coburg Theatre in London, the curtain rose on “Vidocq! The French Police Spy,” a melodrama with all the overwrought dialogue you might expect. (Other plays would follow, mostly after Vidocq’s death.) A few years later, Honoré de Balzac (the two men knew each other) based a character in his novels, the brilliant fugitive Vautrin, on Vidocq.

Vidocq seemed to have made a point of interacting with other famous people within France—it was good for business, no doubt—and he reportedly met mega-author Victor Hugo in exactly the way you might expect: amidst a highly dramatic riot. In the book Stealing Things: Theft and the Author in the Nineteenth Century, Rosemary A. Peters reprints and translates a letter sent from Vidocq to Hugo, who (in addition to penning literary classics) was a representative of the Second Republic, and thus targeted by rioters during one of France’s distressingly regular political upheavals during this period:

“As you were returning home, going down the rue St. Louis, when you were facing that of Douze Portes, the Citizen Cuisinier, extra-red Republican and chief of the insurgents, who had tried to burn your house down, manifested the intention of insulting you as you passed by. To prevent him from realizing his plan, I conceived the idea of shouting and making others shout out Long live Victor Hugo! This chorus intimidated… to the point that he kept silent.”

Whether or not Vidocq was exaggerating the incident for dramatic effect, it’s clear that he made an impression on Hugo, who used the detective as inspiration for two of his key characters in Les Misérables: Jean Valjean (who escapes the law with the young Vidocq’s ingenuity) and Inspector Javert (who echoes the elder Vidocq’s tenacity in pursuing criminals).

Over the past 180 years or so, academics have argued that Vidocq inspired any number of literary characters, from Charles Dickens’ Abel Magwitch, a criminal with a predilection for disguises who manages to make a questionable fortune, to Edgar Allan Poe’s famous detective C. Auguste Dupin. In Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Dupin even calls out Vidocq by name, calling him “a good guesser, and a persevering man… [but] without educated thought, he erred continually by the very intensity of his investigations.”

It’s always wonderful when an author cites a probable influence right in the text. Some connections between Vidocq and fictional characters, however, are a bit more nebulous. In The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq, James Morton even insists that Vidocq’s influence found its way into Moby Dick, Alexandre Dumas père’s Gabriel Lambert, and Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin, the gentleman thief.

While it’s difficult to trace out any author’s influences (especially when the intervening centuries have vaporized much of their correspondence), it’s clear that Vidocq had notable influence on some of the literature’s first detectives. Later crime-fiction authors, of course, drew their inspiration from those early sleuths—which means that Vidocq’s impact is still being felt, however obliquely. His afterlife as proven as colorful as his actual existence.