Unconsciously searching for my own humanity I discovered Super Hero comic books on a metal rack in a neighborhood supermarket in the very early 1960s. The bright colors and derring-do gave my mind the potential first to imagine having superior powers and then, second, to wonder what to do, what was right and wrong to do with that power.

I say Super Hero comics because earlier on I used to read children’s comic books about friendly ghosts, playful child-devils, and variously charactered adolescents. These children’s comics were more about my identity but the latter Super Heroes were something else – they were about making a difference in the world.

The first Super Heroes I was drawn to were Batman and Superman, Green Lantern and The Flash. These were glitzy heroes without much depth but they still offered the notion of great power and therefore the question of how that power might be used. This was just before the onset of the vaunted Marvel Age.

Then one day, late in the year 1964, I chanced upon a used issue of Fantastic Four #15 in a corner market in South Central LA. There was something different about this comic book. The characters didn’t all look the same, they didn’t have the same temperaments, values or natures. They were very different-looking and -acting people who had to work at getting along. And they had to get along in order to fight evil. Wow.

These Super Heroes had to deal with their own natures in order to use their powers without disturbing everyday life. Even some villains had to put limits on their emotions.

I’m thinking especially of Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner. This biracial (Atlantean and surface-dweller) human being had lost his memory for decades and when he came back to himself he realized that his underwater people had been annihilated by the nuclear testing of the surface-dwellers. Namor’s rage informed his relationship to the surface world for many years. He fought against surface-dwelling Super Heroes but wasn’t really a villain. His hatred had reason, history.

That which was lawless but also contained reason. Every child understands this notion but rarely did we have the setting to express it, much less discuss its ramifications.

Also in 1963 the comic Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos was published. This was a World War Two comic and I wasn’t very interested in that war because my father fought in it and I somehow felt it belonged to him. But it was Marvel, and Jack Kirby did draw it so, one day, I picked up a copy just so I was up on the literature.

Therein I found Gabe Jones, I think the first black character in the Marvel Universe. Seeing Gabe told me that in some way and for some reason these comic makers wanted to include my experience in their world. This desire somehow kindled desire in me.

Jones had no superpowers per se, but neither did any of the other Howlers. He could play trumpet. He could laugh and be heroic, as my father had been.

I didn’t much read about Fury and his band until they migrated to the future in Fantastic Four #21, I believe. But still I began, more and more, imagining myself and my world in terms of Marvel. There was a place for me in that world, I knew it.

When the Black Panther appeared in Fantastic Four #52 I was ready for a black Super Hero who could challenge the Fantastic Four, who could build a technological wilderness, who could stand with pride rather than villainy or hatred. It was a seminal moment in my ability to see myself in the world.

This permission to imagine, I believe, is the gift of all comics but T’Challa, the Black Panther, was a special gift to many young black people. Rather than a creation for us, it was a manifestation of our underlying dreams. We wanted him and therefore he appeared.

And, as all comic literature does, this character and his world molded itself to fit the challenges, or perceived challenges, we encountered. For a long time, a very long time, these battles were interpreted by so-called white writers and artists trying to create adventures that mostly adolescent boys could enjoy, even relish.

Over the decades these challenges changed, became more sophisticated, and finally turned in on themselves. The stories in comics were often about good and evil but also an understanding of the concept of justice. So—if I condemn an enemy for committing some atrocity then I must also denounce myself or my friends if we do something similarly wrong.

This is the gift of comic books. They create moral quandary for us in those we admire.

And so we come to Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Mr Coates is a thinker, a political philosopher, a man who rises from the modern age of America. His articles in The Atlantic and his books recast our world in a way we have often suspected but were never fully able to articulate. In short, Ta-Nehisi Coates is a comic nerd of the highest standing.

He grew up reading comic books, considering their moral dilemmas, wondering if he were strong enough, brave enough, courageous enough to do what these heroes did. And believe me, Ta-Nehisi had to be strong. When he was six years old and going to elementary school in West Baltimore his teacher bade the class to rise to salute the flag. Obedient as a rule, Ta-Nehisi rose but he did not cross his heart, he did not utter the pledge.

When the teacher asked him why he was being so unpatriotic he replied, ‘My father told me that I can’t pledge myself to my enemy.’ Something like that.

It was true. The Black Panther, Paul Coates, had told his son that he could not pledge himself to America, that America had not done right by their people.

It is not hyperbole to call Paul the Black Panther. He was the leader of the Baltimore Black Panther Party. On top of that, he and Ta-Nehisi went to the comic book store every week to find out what was possible.

Ta-Nehisi had run the gamut of the possibilities of the Black Panther, starting with his father and going all the way to T’Challa. When he read the comics he wondered how in the modern world an advanced civilization could be ruled by a monarchy. What if the king were unfit? What if his progeny were not qualified to rule? What if the people simply did not want his blood as master?

These are simple questions. And, as we all know, the easiest questions are often the hardest to answer. And so in his five-year run of Black Panther, Mr Coates has tried to understand our love of tyranny contrasted with our desire for freedom; the betrayal of our hearts in spite of the love we feel for our blood.

So, Mr Coates’s journey in the Marvel Universe has been an internal one. It’s not Doctor Doom or the Red Skull we rage against but the complex desires that drive our humanity to the heights of sophistication and the depths of depravity.

In this world we face off against ourselves in hyperreality. We are the black slavers who sold our sisters and brothers to foreigners. We are the dictators jealously protecting our loot. We are the victims of a vile hatred that is older than our oldest member.

The following illustrated pages are the distillation of fifty-five years of progress made by dozens of artists and writers finally coming down to Ta-Nehisi Coates and his compulsion to ask why.

It is, in part, the whole philosophy of Super Hero comics and its hold on the modern imagination.

___________________________________

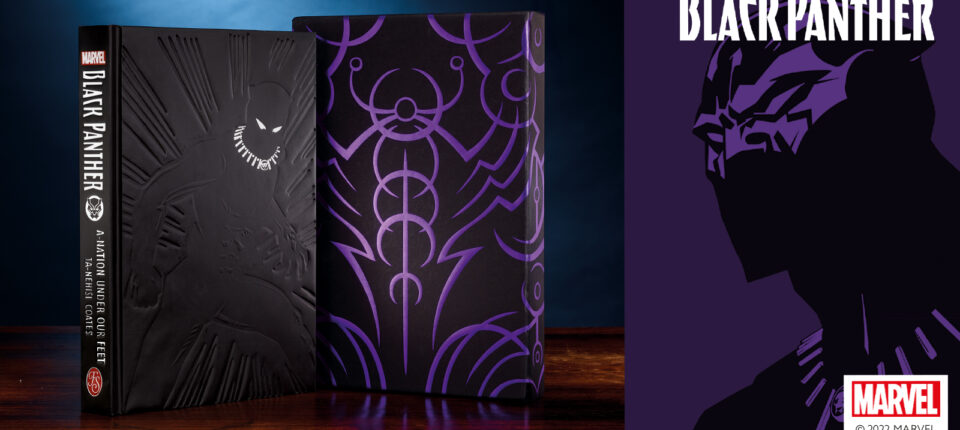

Excerpted from Black Panther: A Nation Under Our Feet, introduced by Walter Mosley, written by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and illustrated by Brian Stelfreeze. This edition is available exclusively from The Folio Society.