For decades, journalist and novelist Wayne Hoffman had heard the story of how his great grandmother, Sarah Feinstein, was murdered in Winnipeg, Canada in 1913. A Russian Jewish immigrant, Feinstein, so the family story went, had been shot by a drive by shooter while sitting on her porch nursing her youngest daughter. It was a crime that was never solved. While Hoffman’s grandmother (Feinstein’s daughter who was only three at the time of her mother’s death) and his mother, Susan, had recounted this story as fact, he always had a suspicion about the truth of Sarah’s death.

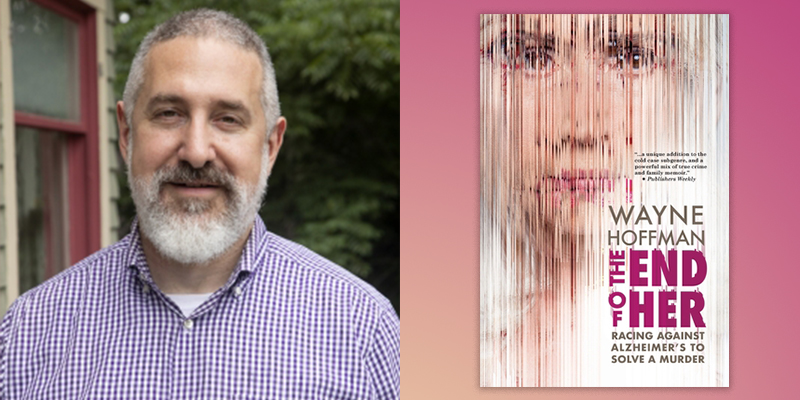

Those suspicions would eventually turn into his own investigation, taking him into the archives and the history of Jewish life in Winnipeg in the early 20th century to uncover what really happened in 1913. In The End of Her: Racing Against Alzheimer’s to Solve a Murder (published this month by Heliotrope Books), Hoffman recounts his efforts to correct the family history and solve this cold case, detailing the twists and turns of his research. The book also details a deeply felt memoir about Susan’s struggles with Alzheimer’s and the loss of her own memories that had kept the family history alive. Like the best of true crime memoirs, The End of Her captures the social and personal traumas of a crime’s aftermath—even one that is three generations old.

I spoke with Hoffman about the challenges of investigating a cold case murder that was also part of the family history.

JAMES POLCHIN: The story of your great grandmother’s murder that circulated among the family lore was that she was shot on her porch by a drive by shooting. You distrusted that story for years, and indeed that was not at all how she was killed. Why do you think that version took hold and was believed for so many decades?

WAYNE HOFFMAN: This is one mystery I can never solve! I reached out to dozens of cousins, most of whom I’d never even heard of, and not one of them had ever heard this legend: Most heard nothing at all about the murder, and a few knew bits and pieces of the truth, but nobody else had heard about a drive-by sniper targeting nursing mothers on their porches. This was my grandmother’s story. She was just 3 years old when her mother was killed, so she wouldn’t have remembered the actual events first-hand. I don’t know if someone else told her that story when she was growing up, or if she made it up for herself, and in either case, I don’t know why. It’s not like it’s a less traumatic story, or less scary. In some ways, it’s even more bizarre and terrifying.

POLCHIN: While the book is about this unsolved murder, but it is also a story about the Jewish community in Winnipeg in the early 20th century. What surprised you most about that history?

HOFFMAN: In some ways, the story of Jewish immigrants in Winnipeg parallels the story in New York City—which is a history I know better, since I live in New York, and most of my ancestors first arrived here: Huge numbers of Yiddish-speaking Jews, fleeing pogroms and persecution in Russia and Eastern Europe in the early 20th century, came to both cities to build a new life, crowding into poor urban neighborhoods and building a dense and strongly cohesive community; years later, they’d gradually move to other parts of the city and beyond, as they assimilated and their economic status grew. So there are parallels. But I hadn’t appreciated the difference: When my ancestors came through Ellis Island, New York was already a massive metropolis of millions; when my other ancestors arrived in Winnipeg around the same time, it was basically a frontier city just a few decades old, with tens of thousands of residents. And when some of those relatives moved to Saskatchewan to buy and sell cattle, they weren’t moving to existing towns and cities at all; they were actually helping to create new towns along the new railroad lines, moving to tiny hamlets on the prairie that hadn’t existed the year before—brand new towns that were almost exclusively inhabited by new immigrants. That’s a very different experience from living on the Lower East Side of Manhattan! I had no idea my own relatives were part of that. Cowboys, ranchers, living in remote, rural places I’d never imagined Jews living.

POLCHIN: Working on a historical true crime comes with a huge set of hurdles. I appreciated how you made explicit your own research process, practically becoming a detective in your investigation into the case. But the mysteries were many. In particular, the press accounts you uncovered, both from the English language newspapers and the Yiddish newspapers, offered contradictory and at times confusing stories about the facts of the crime. What was one of the biggest hurdles you encountered in trying to get to the truth about your great grandmother’s murder?

HOFFMAN: The biggest hurdle was trying to find everything about the murder. If I’d stopped earlier, after I found the first few newspaper stories, I would have had a very different impression of the crime: Police had a theory almost immediately, they had suspects in custody within two days, with an inquest scheduled for that week. It seemed like an open-and-shut case. If I’d stopped reading after I found those initial stories—which a few cousins I met had done, while doing their own family research—I would never have known just how quickly the whole case fell apart, and how the case would ultimately go unsolved. Mind you, digging up some of these other newspaper reports—in English and Yiddish, from across Canada, from publications that no longer exist—took quite a lot of time and persistence. If I hadn’t been focused on learning the whole story, I would have stopped much sooner and thought I’d found the truth, even though it wasn’t the whole truth.

POLCHIN: What’s intriguing is the layers of facts and what you call “gossip” in the accounts of the murder. Crime stories are often not just about the crime itself. Through press accounts in the weeks and months after the murder as well as the testimony at the inquest, you show the many contradictions and uncertainties that swirled around the investigation. Given your research, what does this crime tell us about that time and place?

HOFFMAN: It’s somewhat shocking to read some of the ways the newspapers referred to immigrants at the time. For instance, there was one newspaper that bucked the others in saying an early suspect was probably innocent—but their reasoning was that he was a swarthy “Galician,” someone from what we’d now call Poland, and they said those people were basically too stupid to commit this crime. And they were constantly complaining about how excitable and prone to gossip the Jews are. So the coverage tells you a lot about the larger public’s bias: journalists who don’t particularly like or understand Jews writing about a crime that was probably motivated by anti-Semitism.

“[T]he coverage tells you a lot about the larger public’s bias: journalists who don’t particularly like or understand Jews writing about a crime that was probably motivated by anti-Semitism.”–HoffmanPOLCHIN: At one point you quote a 1913 news account in which the Chief of Detectives investigating the murder states: “[t]he greatest difficulty we have to contend with is the many garbled stories which are told us by people who either knew, or think they knew the story of a woman’s life.” This detail was striking and felt like a theme throughout the book as you recovered the realities of Sarah’s life but also the lives of other women in the family and those involved in the case. What was the challenge in recovering the stories of these women?

HOFFMAN: The first thing I noticed in my research was just how much harder it is to find information about women from earlier generations—because their names vanished in official records as soon as they got married. If you don’t know their married names, you can’t search for them. So it was easy enough for me to discover documents about my great-grandparents’ brothers and sons, but not their sisters and daughters. And while I could discover a lot about the men in my family from things like business directories, voter registration rolls, and census reports, there’s much less information about the women. Even in front-page stories about my great-grandmother’s murder, the newspapers called her “Mrs. David Feinstein.” She had been born Shifra Averbuch, shortened her surname to Brooks in North America, adopted the English first name Sarah for use in official documents (but not in her own everyday life), and then taken her husband’s name when she married. That’s a lot of steps: If you’re looking for Shifra Averbuch, you’d have to know all of those steps to understand that the newspaper story about “Mrs. David Feinstein” is about the same person. And women’s lives more broadly, like women’s names, just weren’t deemed important or newsworthy in most historical sources; a lot of these women worked, but where? There’s no record of it. Men had “professions” that showed up on census forms and immigration forms. Women didn’t; even if they had jobs, they often weren’t considered worthy of note.

POLCHIN: While the book details your investigation into the murder, it is also a story about your mother’s decline with Alzheimer. Can you talk about the form of this book and why you decided to intertwine these two stories?

HOFFMAN: At first, I was just curious about the murder. I hadn’t intended to write a book. I thought I’d find out quickly what really happened, sum it up in a few words, and tell my mother, and that would be it. Once I realized it was a bigger story, I thought about writing a whole book about the murder. But my research kept getting put on hold because my mother had much more immediate needs, so I’d put the book on the back burner—for months or even years at a time—while I focused on her. And then I remembered what Ellen Willis, one of my journalism professors, once told me: If you’re trying to write a story but you can’t get past an obstacle, then that obstacle is your story. In other words, my mother’s illness, and my involvement in taking care of her, was an integral part of my research into the murder. By the end, I couldn’t think about one without thinking about the other. My mother’s illness is what drove me to delve into this mystery—so I could solve it before she lost her ability to understand what I’d found—but it’s also what prevented me from devoting more energy to it for many years. For the past decade, those two strands have been intertwined in my own life.

POLCHIN: Lisa Levy has written that true crime memories show how the tragedies “irrevocably change the lives of the individuals and their families.” In searching for the truth of this murder, do you think it has also changed the way you see your family and its history?

HOFFMAN: Very little about the murder was ever discussed in the family; some relatives didn’t know anything about Sarah, much less that she’d been murdered. I think that, at the time, not talking about it was supposed to be better for the kids—better not to scare them with awful stories about violence and death. But what I found is that the silences, too, left scars, and those scars have endured for a century. Because it was clear to all the kids and grandkids that something traumatic had, in fact, taken place, but they’d learned implicitly that they shouldn’t ask questions, and that painful things shouldn’t be shared, not even within the family. That’s not a great recipe for emotional wellbeing.

POLCHIN: Right, and to carry on with that idea, memory is a powerful theme throughout the book. At one point, as your mother’s illness became more acute and she struggled with remembering who you were, you wondered if your entire life would one day “vanish from her mind?” Your investigation was as much about uncovering the truth of Sarah’s death as it was rectifying the collective family memory. What were the connections between personal and historical memory for you in writing this book?

HOFFMAN: Part of my mother’s personal history was being the keeper of the family’s historical memory. It’s a tricky thing for a lot of North American Jews, because often our family histories only go back a century or so; the “Old Country” was never, ever recalled with any shred of fondness, so family histories always began with the arrival in the U.S. or Canada. But still, my mother was the one who collected these stories, knew the family tree, and kept track of people—even from a distance—long before social media existed. So my mother losing her memory also meant our whole family was losing its history. Part of my mission was to collect that history, and preserve it, when she no longer could.

James Polchin is an Edgar Award nominated writer, cultural historian, and author of Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall (Counterpoint).

Wayne Hoffman is an award-winning novelist and journalist, and author of a new true-crime family memoir, The End of Her: Racing Against Alzheimer’s to Solve a Murder (Heliotrope).