When the world is on fire, I turn to historical thrillers. When my personal world is full of fear and anger, I find comfort in Nazi henchmen and Communist spies. When I was pregnant during Australia’s Black Summer bushfires, I read Bernie Gunther like he might save me from inhaling smoke. I read Alan Furst’s gentlemen spies of eve-of-war Europe in hospital, with a newborn, in the first fearful days of the pandemic. I write this as Sydney goes through another lockdown. After a week inside, I dropped what I was reading and picked up the next Maisie Dobbs crime novel, set in the first days of World War Two.

This is not merely a preference; it is a necessity. But the only way I can tell you why is through the books themselves. I want to look at three authors and series—Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther series, Alan Furst’s pre-war Europe spy novels, and John le Carré’s Cold War novels—and through them, hope to explain how and why historical thrillers are the perfect books for the end of the world.

Why I love Phillip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther

I love Bernie Gunther. When we first meet him, he’s a cop in 1930s Nazi Berlin. We travel with him all through World War Two, when he becomes an SS officer and works for worst of the Nazi hierarchy, and then through his aching displacement in the post-war world. He is witty and cynical, romantic in the face of horror, determined, selfishly selfless, and honest with the reader.

The books are written in the first person, as Bernie tells us his story, often in flashback from a quiet spot where he hopes to lick his wounds. I love a first-person narrative, its direct storytelling, making the reader a complicit confidante in all the narrator thinks and does. In crime or spy fiction, this closeness can signal two things, and sometimes both simultaneously. The direct voice lets us explore the intimate emotions of a situation—the horror of the crime or the tension of an upcoming mission—it’s the opposite of a news report. But the first-person narration is also a disguise, a way of lying to the reader by repainting the truth. When the narrator is a man like Bernie Gunther, unavoidably involved with the Nazi regime, the line between intimacy and manipulation can seem very thin. For me, this is exactly right, as it lets us explore the moral complexity of living in a corrupt world.

As a policeman under Nazism, every action he makes is political—he can’t help it, as the laws he is meant to uphold keep changing, so that murder is no longer murder and corruption no longer exists. When the war begins, he is automatically made part of the SS, the elite of Nazi soldiers, and asked (forced) to work personally for Goebbels, Goering, and Heydrich. Here, the crime novel takes a wonderful turn, as Bernie is no longer investigating the crimes but part of them. His first-person narration becomes especially tortured in these books—how, he asks, can justice become so divorced from the law? His SS uniform means that even being a witness to war crimes makes him complicit, and he is a witness; what, then, is the point of solving the murder of a single man?

His narration becomes darker and darker with each book, as the history of his country crushes him. But this is a crucial issue in narratives of World War Two—what does it mean to be good when the world you live in is so bad? How can you live in an evil regime and not become part of it? The books explore how a country can tilt and fall into totalitarianism. Through Bernie, I can test ideas of moral courage and ethical living, the heroism of survival and what survival means, and take the results of these tests of imagination into this world with its disease and riots and fires. And unlike now, of course, I know the ‘bad guys’ lose. When the world is on fire, I can’t deny this is a comfort.

Why I always reach for another Alan Furst

Furst’s spy novels are not a series, but they reflect each other. They are all set in Europe, and often in Paris, between 1936 and 1942. His spies are rarely professionals, but rather amateurs who become part of an underground resistance. Almost all of his lead characters are men, about 40 years old, still handsome if a little silver at the temples, single but with strong romantic yearnings, and fiercely anti-fascist. The spy missions are mostly successful, a tiny triumph in a wider landscape of violence and evil.

Furst’s spies are on the right side and their sacrifices are meaningful. While I can’t see myself as Bernie Gunther’s accidental SS officer, I can see myself as the amateur pulled into heroic work by the force of historical circumstance. I want to see myself this way, that I would be heroic if my country needed me—no, that I am heroic, that my outrage isn’t impotent and I can fight the system and make a better world. That my efforts, however small, are part of a larger pattern of resistance and, hopefully, change.

These books also look at the swell and rise of fascist societies and what people can do when they find themselves in a morally toxic world. Furst is not interested in historical monsters but at how these corrupt systems take hold. His is a ‘ground-floor’ view of politics, the view of ordinary people who navigate a shifting political landscape on their way to work. Politics is in the smallest actions, whether that’s a letter sent or a coffee accepted, turning up at a rendezvous or being strategically absent. It’s how fighting the good fight happens one train trip, one dispiriting meeting, one cold lonely night at a time. Spies are people engaged in change, sometimes through the most mundane of tasks. This gives me hope, and through hope, resilience.

And, of course, there’s Paris. Furst lived in Paris and the tenderness he has for the city is in every paragraph. Paris is melancholy, romantic, full of stern facades and hidden gems, difficult and always worth it. Sometimes I read his work only for the writing about Paris and his imagining of how people lived in the city in these years.

But I also read his work for his distinctive style. He is precise in his detail and his action, never overly emotional, his characters as elegant and subtle as Paris itself. When my world is overburdened with emotion, when everyone is screaming and crying, on TV, on social media, on the end of the telephone line, in their cot, then Furst’s submerged passion is hypnotic. It took me a while to get used to it though. It took until a bushfire and a pandemic before I could see what was hiding in the shadows of his Parisian alleys, of what the stoic heroics concealed. His books have plenty of sex but very few tears, everyone grits their teeth through the pain and then releases the tension in drink and the nearest willing body, before heading back into the intrigue of a Paris boulevard in 1939, collar turned up and shivering in anticipation.

Why I sing praise to Cold War le Carré

Technically, these are not historical thrillers—they are just thrillers, written about their contemporary world. But reading them now, thirty or forty or fifty years later, they feel like historical documents. The details of telegrams and landlines, of tea ladies and tailors, is as period as any historical novel. It would be mannered, were it not for le Carré’s excellent prose, and for the way he uses spy novels to talk about what it means to be human.

Le Carré’s style is the most literary of these three authors. If you read the books in order of publication, his work just gets better and better, his ideas more sophisticated, his prose more lyrical. I’ve just finished A Perfect Spy, with spy Pym writing to his son about his younger days. Pym constantly refers to himself in the third person, as though he wasn’t in his own life, as though his every action was a performance for an audience of one other body, for his reflection—before the text flips to action sequences of the real-world consequences of Pym’s absurdist personal drama. Yes! I think, Yes, this is exactly what this genre should do: use the strict framework of the spy novel to explore what it means to be a person in the world. This book turns the spy novel on its head, where the main spy is the quarry and the mission is to find the spy who doesn’t even know where he is except in the most basic, literal sense. This is really the personal face of politics, of every friendship limited and adulterated by the larger world, and the larger world no more than the small but all-consuming connections between people.

In the Cold War novels (that I have read, at least) the characters confront the ideas of the worthy sacrifice, of embedded failure, of the links between identity and memory. Le Carré’s is a very male, very British world of difficult, diffident, slightly rumpled liars. They are men who are tasked with upholding an empire, who fail again and again, their justifications for colonization falling apart as soon as they are uttered. Smiley is always about to retire, he is retired, he is doing one last favor; their world, their way of life, is always ending. The books are written looking back—remember when this happened? the narrator asks—analyzing what was worth sacrificing and what, in the end, was a waste. The books ask, who is a spy if all his best work is unknown and will remain that way? Does he even exist if everything he does is denied, if even those he loves don’t know him? What is memory, the core of identity, when it is contradicted by the official narrative, when the scars you bear do not and have never existed? To have these thoughts about my own, ordinary, life feels ridiculous. But when these ideas are put into a spy context—how the tiniest action can have the biggest consequence, where to disappear is part of the role, where truth is a matter of the manner of telling—then ideas of what makes a person, of the relationship between truth and tale, become big, bold, and dramatic, and I can think through my own issues via the book.

Of course, to do this I have to be Smiley, or Ned, or Pym. I’m not Pym’s wife Mary or Smiley’s wife Anne, I’m not Connie or Molly or any Soviet femme fatale. Likewise, I’m not one of the unlucky women that Bernie either fights or falls for, nor am I the love interest of a middle-aged amateur spy, even if she is a spy herself. I am the one who goes into the darkness to effect change. I am the mover, the person of action, the chosen one. But I would like to do that without having to imagine myself as a man, in a world of straight white men.

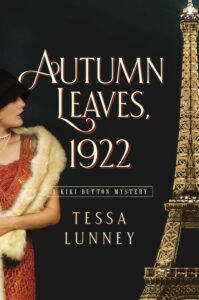

So I wrote my own.

I have stolen a lot of ideas from these three authors. I have taken the sassy first-person narration from Bernie and put it in Furst’s Paris. I have taken Furst’s reluctant amateur spies and teamed them with Gunther’s cast of real-life characters. Le Carré’s colonized people and off-stage women stalk Furst’s boulevards and are as fierce as anyone Bernie fell into bed with. I have taken courage from le Carré that larger ideas have a perfect place in the thriller, whether loud like in Kerr, subtle like in Furst, or playful and sophisticated like in le Carré himself. I have written out what I didn’t like—too much violence, too much repetition, too few women. I have added what I needed—strong women, women with responsibilities, women who make their own way in this world. I have written out some of the straight white men and replaced them with characters more suited to the world we know. I have done this far from perfectly—I’m still learning this craft—but I will keep reading and keep learning to write better, plot better, be braver. The world is still on fire (even the ocean is on fire at the moment—we have done the impossible), so I will keep fighting for change and I will keep reading historical thrillers, as the world is endlessly falling apart, and I need them.

***