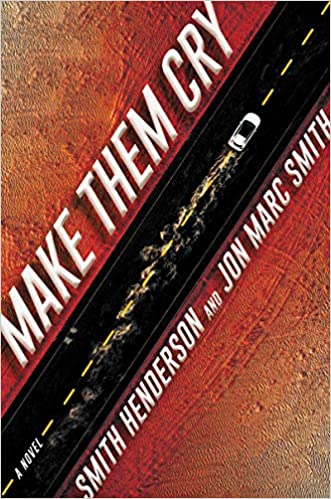

The upcoming novel, Make Them Cry (Ecco, 2020) follows a prosecutor turned DEA agent on her journey to Mexico to root out a dangerous secret about a drug cartel. The novel is a pounding, relentless thriller reminiscent of the very best of 1970s conspiracy fiction. It was written by two authors working together, Smith Henderson and Jon Marc Smith. We asked Henderson and Smith to share some insight into the book’s origins. Here, the authors discuss the process of remote collaborative writing, letting go of ego, motivation, why plots are like jokes, and the origin of Make Them Cry.

Smith Henderson: The most common question I get about our book is some version of “Whoa, how do you write a novel with someone else?” Honestly, people seem more interested in our process of writing than the book itself.

It can be fun to go into the nitty-gritty of the creative process. Virtually everyone has been made to write at some point, and they certainly remember what a private and complicated process it can be. So how did we write a whole book together? My answer is usually some version of we opened up a shared Google doc and just started banging it out.

Jon Marc Smith: I think the interest arises because lit’ry people are highly individualistic, so they have trouble imagining actually working with someone else on something as ostensibly personal as literature. We’ve been told from the time we first get taught Edgar Allan Poe or Laura Ingalls Wilder (I chose them because, like serial killers and myself, they have three names) that imaginative writing is suffused with the self, in fact we should read novels explicitly as a kind of storehouse of self, so those of us indoctrinated by English teachers ending up believing that our sentences are ourselves. They’re not, but that doesn’t mean they don’t feel that way when you’re a sensitive writer-type.

Inherently, I understand why the idea of working with someone else on a novel is baffling. And when I was a young, I wouldn’t have understood, either. How can you collaborate with someone on your sacred work? But as I’ve gotten older and less young-man-ish I’ve also become, I hope, less egotistical and precious. When you’re collaborating, you can’t dominate or be a brat about your own ideas. It doesn’t matter who had the idea, or wrote the sentence, or tweaked the phrasing. Ninety percent of the time, ideas came from the dialogue between us. Asking who-did-what is exactly the wrong question: it doesn’t even make sense on a project like this. One thing this book taught me is what matters is the work. And that’s why you and I are constantly saying Mamet-y things to each other like, “THIS is the job.”

Smith Henderson: Yeah, you can’t do this kind of work for long if the only thing that gets you going is the froth of inspiration. It does, however, take a tremendous amount of ego to even think that you should write a novel, that you have something worth saying. Writing together is really comparable to ad agency and television writing, which are both tons of fun. Actually, we should mention this: we’ve been working on Make Them Cry and writing in that world for so long, and we had originally conceived of it as a screenplay.

Jon Marc Smith: We wrote multiple versions of it as a script, some of them very far afield from the original idea, depending on what kind of ridiculous notes we were getting at any given time.

Smith Henderson: The notes from management! It was so predictable: the feedback would always be based on whatever movie was doing insanely well at the box office. They’d ask if it could be more like Inception or something that had nothing at all to do with our project. I thought I’d gone insane after some of those calls. I’ve since realized that they really needed a way to describe what the project is in the simplest terms: how can they sell this? Hollywood is full of literate, creative people. But in a world of a gazillion scripts, what stands out has to be like a great joke: simple enough that anyone can tell it.

Jon Marc Smith: It’s hard to write a good joke. Or screenplay. We had no idea what we were doing when we first started writing screenplays thirteen years ago. There’s no way we would’ve been able to write a book if we hadn’t gone through that process together of teaching ourselves screenwriting.

Smith Henderson: That partnership, as screenwriters, was pretty formative in our development. We always have that hunger for momentum and plot that is so central in screenplays. Those screenwriterly tendencies are really important guardrails. The trick for us was elucidating a few ground rules—not owning sentences, not reporting thoughts, deciding on tone and voice.

Jon Marc Smith: Also, not looking at each other when we’re FaceTiming.

Smith Henderson: Yeah. I’m in so many video meetings nowadays that it’s truly refreshing that we just do audio conferences. Actually, I really like our rambling conversations, which are often pretty inspiring. Which brings me to one of the advantages of collaboration that I don’t talk about very often: motivation. I don’t know if I motivate you, but, Jon Marc, you certainly motivate me. Not in the rah-rah sense but just in the collective effort, the obligation. I remember when we realized that we’d written the wrong book and started over (yes, that happened!), it took a gut-check to continue on, but we did.

Jon Marc Smith: It was the right call.

Smith Henderson: Even though we had a contract in hand, I just had this terrible feeling we were too far into the story and needed to go back to the drawing board and made what eventually became Make Them Cry

Jon Marc Smith: We were doing too much explaining. We needed to introduce the world. I’m still mad at you for realizing that!

Smith Henderson: It was very difficult to admit and do right by the project. Devastating to the ego, at least. But I never once thought of abandoning it, mostly because it was a thing we were doing.

Jon Marc Smith: Having to start over was, as you say, devastating. I definitely was wishing I could quit the book, as Jack Twist might say if he were a writer and not a cowboy. It felt like losing a fight or an election or something. How do you get up the next day and go on?

Smith Henderson: Well, since the coronavirus has hit, so many of my other projects, projects I’m working on my own, have seemed thin or weird or the wrong idea for the moment, and I’ll likely abandon them or set them aside. But this book—and the series we intend to make of it—well, I’ll never quit on it. Is it because we actually have that much fun working together? I think that might just be it. But I also feel a deep obligation to continue because we’ve both put so much into it.

Jon Marc Smith: I do feel like we owe it to each other to keep working on the series. There is no way we’d have been able to start over if we didn’t trust each other. That’s the most important ingredient for collaboration, I think. You have to believe in the other person, which is no easy task in a world like ours.

“That’s because novel writing itself is not important . . . And yet you have to treat the book you’re writing as an absolutely essential, fundamental thing or else it’ll suck.”Having some kind of thing you’re working towards—not a goal exactly, more like the potentiality of the project, I suppose—that’s an important thing for a writer to have. That’s because novel writing itself is not important. In some ways there’s nothing less important than it. And yet you have to treat the book you’re writing as an absolutely essential, fundamental thing or else it’ll suck. It may be terrible anyway, but it will for sure if you don’t work as if you care deeply about it. Having someone else involved with you is a way of caring.

Smith Henderson: I like what you said about how you have to treat the work like it’s really important. There’s something to be said about how we—and most good collaborations—function, and it really is rather simple: you just create space for the other person to do good work.

Jon Marc Smith: That’s a big part of it for sure. There’s no way to do this without coming to an agreement that no sentence is owned or too precious to be changed. This requires some disassociation. The work is the important thing, not us as individuals.

Smith Henderson: I don’t think we’ve ever had a strong disagreement over anything, but I’ve definitely re-revised a paragraph or sentence that you’ve then gone and changed back into something I didn’t love.

Jon Marc Smith: Our biggest disagreements were probably over interiority. Neither of us are huge fans, but I’m definitely more tolerant of it.

Smith Henderson: I have a knee-jerk reaction to being told what a character is thinking.

Jon Marc Smith: The pressure you brought to bear—honing down thoughts and emotions and manifesting them in physicality and drama—made the story much, much better. At the same time, we both believe fiction should be an exploration of thinking and feeling people. Characters aren’t automatons, after all. It’s about finding the right balance. I don’t think we would’ve been able to find that without something of a dialectic.

Smith Henderson: Absolutely. An aesthetic dialogue. I prefer to witness the character thinking. What passes for interiority is too often just reporting characters’ thoughts. I want to see how mental activity leads to action and vice versa. But I’m fussier than you, even. I get really hung up on timing stuff, like characters’ work schedules. I’m always worried that a character couldn’t do such-and-such because they live far away or they have a vet appointment. You love those conversations!

Jon Marc Smith: I’m actually grateful for those arguments, because the byproduct is shoring up weaknesses in the narrative. The funny thing is, coming up with the voice of the thing was way easier than the plotting. Am I right about that? Is it just that voice is easy and plot is hard?

“Anyone can learn a joke, which is another way of saying anyone can learn a plot. But telling a joke well, that’s voice.”

Smith Henderson: I bet a lot of people think it’s the other way around. Maybe this analogy works, and touches on what we said earlier about jokes: Anyone can learn a joke, which is another way of saying anyone can learn a plot. But telling a joke well, that’s voice. Most people are loathe to speak in public, so voice seems like the tricky part. But here’s the thing: plot isn’t learning a joke—it’s writing an original joke. And that is…incredibly difficult.

Jon Marc Smith: That’s a terrific analogy. Jokes—just like scenes and stories—are conflict-dependent. But I’d argue that some kinds of jokes are easy. If you’re funny, you can write a one-liner. But it seems to me that longform comedy—the kind of “jokes” we get from a Richard Pryor or Norm MacDonald—is way more challenging for both audience and performer. That’s because manifesting abstract ideas in structured dramatic form is difficult.

Smith Henderson: Hard agree. And of course, Norm and Pryor are masters of voice too. For us, once we established the voice, we really got rolling. You might be off doing the thankless work of making a first draft of a chapter and then I’d jump in and start building on it. And then you’d be off doing some research and bring that to bear on a new revision. And then maybe I’d see that we have a big problem in the next chapter and we’d have to talk it out. I really loved that part—being able to talk with someone who is as invested and knowledgeable as you are…is incredible. Honestly, I feel sorry for myself when I’m working on something alone, because I can’t really turbocharge the process like we can by having a partner to talk it out.

Jon Marc Smith: It’s so much harder when there’s nobody to ask. Even the fact that someone is changing sentences or changing back sentences (ha!) is a sign that the thing is alive and real. Writing alone is almost like if I throw it off a bridge and there’s no one around, will anyone hear the splash? if I delete the whole thing, will anyone care? When you’re working with someone, it’s still real and solid, even when you’ve got to start over.

Smith Henderson: We should probably wrap it up, but what are some of the influences you see in our book? Films, books, music, art…? Anything that went into the making of this for you (or me)?

Jon Marc Smith: A huge amount of the inspiration for this book came from non-fiction, mostly by Mexicans or Mexican-Americans, many of whom risked their lives to report on and analyze the ongoing drug war, which is in its third (or fourth or even fifth) decade. Los Zetas, Inc. by Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, Narcoland by Anabel Hernández, A Narco History by Carmen Boullosa, El Narco by Ioan Grillo, Midnight in Mexico by Alfredo Corchado, among many others. . . . The bravery of the people who do frontline reporting is just astonishing. I wish we had a better word in English for what they do than “non-fiction” or “journalism,” something that would get at all the skin they’ve got in the game. You and I have done our share of research, but we haven’t had guns pointed at us. (It’s been a long time since someone shot at me, and never in Mexico.) There are some truly great books out there written by people who have taken real risks.

But we are novelists, after all, so why not get into some of that, too. To me, Le Carré is like the Proust or García Márquez of thrillers. Okay, maybe not quite that, but he’s pretty high up there. Interestingly enough, considering what you say above about plot, it’s the interiority of Le Carré’s characters that’s the most compelling. His plots confuse me, even though I trust him absolutely. To me, there’s something great about a book where you cease caring about what’s happening and are mostly concerned about the who it’s happening to and what the spiritual consequences of those happenings are. Maybe that occurs in some books because the plots don’t matter or don’t make sense or are insufficient, but that’s not the case with Le Carré. With him, the plot’s there, it’s as tight as a movie if you think about it, but you don’t want to think about it because there’s all this other stuff going on inside.

There’s a great line in Heart of Darkness when the phrenologist doctor tells Marlow that he doesn’t measure the skulls of the men coming back from Leopold’s Congo because the changes take place inside. I hope we’ve been able to get that across in Make Them Cry, the spiritual need and desolation that spring up from lives lived on the edge of violence. Ours is to some degree a popcorn book—we actually want the audience to be thrilled reading it—but I hope that we also got across at least a tiny bit of the tone and depth of Le Carré, Conrad, Graham Greene, Roberto Bolaño, all of whom wrote deeply and perceptively about the world of crime and criminals and the shadowed waters where capital seeks its own level.

— Make Them Cry will be published by Ecco on Sept 22, 2020.