Considering how many mystery novels—old as well as new—have made knotty intellectual puzzles central to their plot development, it’s no surprise that book designers should have been inspired to also incorporate puzzles into the appearance or physical construction of these publications.

An early example came from London-based George G. Harrap and Company, which in 1934 issued at least three hardcover books with jigsaw puzzles built right into them. The initial “Harrap Jig-Saw Mystery” was the British impression of Erle Stanley Gardner’s first Perry Mason lawyer/detective yarn, The Case of the Velvet Claws. Like its successors—J.S. Fletcher’s Murder of the Only Witness and Leonard R. Gribble’s The Secret of Tangles—Harrap’s Velvet Claws had a pocketful of jigsaw puzzle pieces bound inside its cover boards, which, when properly assembled, provided a visual solution to the case described in the story. In addition, the final section of each book’s text was evidently sealed to prevent impatient readers from skipping to the end.

Three decades later, Bantam Books revived the puzzle theme, if with less-innovative results. It hired The New York Times Book Review’s well-respected crime-fiction columnist, Anthony Boucher, to select five “great novels of detection,” which he did in short order: Ellery Queen’s serial-killer thriller, Cat of Many Tails, Christianna Brand’s Green for Danger, Helen McCloy’s Cue for Murder, Georgette Heyer’s A Blunt Instrument, and Hake Talbot’s locked-room mystery with a supernatural twist, Rim of the Pit. In 1965, Bantam reissued all of those books as consistently styled paperbacks, each featuring a brief introduction by Boucher and presenting cover art that employed various jigsaw puzzle effects.

And then came Dell Books’ Murder Ink/Scene of the Crime series.

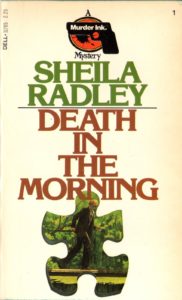

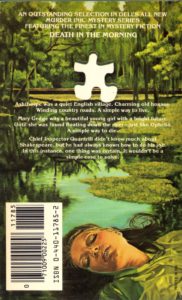

Dell remains famous for its mid-20th-century string of “mapback” editions, softcovers that boasted striking and frequently useful crime-scene illustrations on their rear sides. Its Murder Ink/Scene of the Crime series, launched in the fall of 1980, was neither so ambitious nor so unforgettable as that. However, its two inaugural entries—Sheila Radley’s Death in the Morning, originally brought out in 1978 and marking the debut of English Chief Inspector Douglas Quantrill; and Australia-born author Mignon Warner’s trial outing for clairvoyant sleuth Edwina Charles, A Medium for Murder (formerly A Nice Way to Die, premiering in 1976)—promptly gave the brand a distinctive, easily identifiable “look.” What’s more, explains one of that line’s former editors, Bob Mecoy, the books “tap[ped] the on-the-ground, specialist intelligence of the two most successful mystery specialty stores in the country.”

As editorial consultants charged with helping to steer its new series, Dell enlisted Carol Brener, who owned the landmark Murder Ink bookshop, established in 1972 on New York City’s Upper West Side, and Ruth Windfeldt, the proprietor of Scene of the Crime, another popular haunt for mystery-fiction enthusiasts, opened in 1975 in the Sherman Oaks neighborhood of Los Angeles. Each of those women was asked to pick half a dozen titles every year—all of which had previously appeared in hardcover—that they believed deserved reprinting. Windfeldt tells me it was “a nice experience. The Dell Publishing team was cordial and positive. Of course, best of all was the personal interaction with the customers—they looked forward to reading, discussing, and collecting each month’s selection.”

Mecoy, who now works as a literary agent in Manhattan, remembers that Brener and Windfeldt shared “a deep and abiding love of what were then called ‘cozy’ mysteries (not terribly bloody, sexy, or complicated),” and they had to work “within a pretty strict budget…that [meant] the books they purchased were typically not wildly successful or awfully expensive to buy.” Nonetheless, says Mecoy, the field of prospective acquisitions supplied enough gems that the pair “occasionally argued over who got which book—adamantly arguing that they’d spotted this or that author first (Jonathan Gash and Simon Brett were both hotly disputed).”

More than 70 works, by authors either already eminent or up-and-coming, were eventually marketed under the Murder Ink/Scene of the Crime imprimatur.

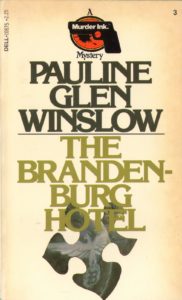

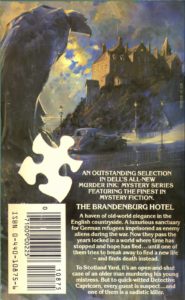

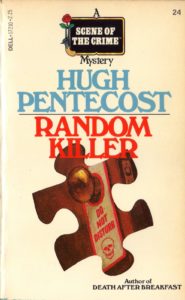

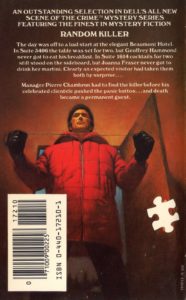

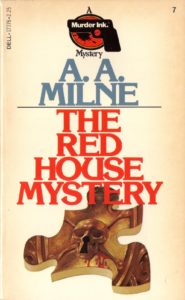

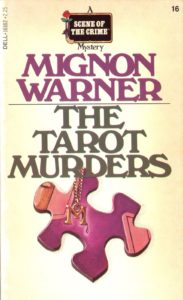

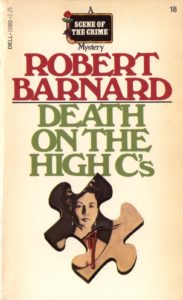

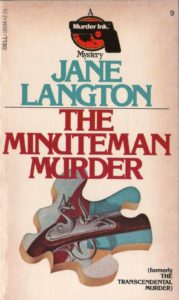

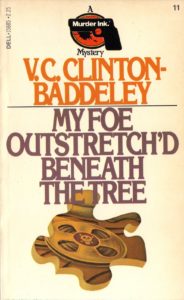

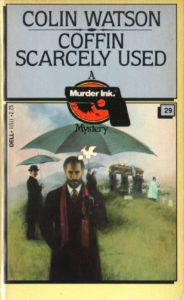

Part of what distinguished at least the early Brener/Windfeldt offerings—all numbered in order of their publication—from myriad other tales packed onto bookstore shelves was their cover format. Beginning with Death in the Morning and running through the 28th series installment, Alan Hunter’s Gently with the Innocents (released by Dell in September 1981), the fronts of these works were principally white, with single jigsaw puzzle pieces positioned below the author’s byline and the book’s title. The gimmick was that those oddly configured fragments fit into fuller illustrations on the backsides of the books (though they were usually enlarged for easier readability). So you had to flip each volume over not only to read the plot précis, but to appreciate the complete artwork.

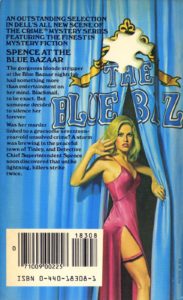

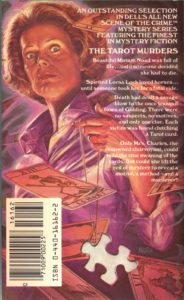

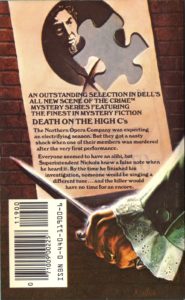

At a time when many U.S. publishing houses were doing away with specially commissioned art for their covers in favor of cheaper photographs, these “puzzlebacks”—not their official designation, but one that couples well with Dell’s prior mapbacks—were still being graced with original paintings, their subjects likely to catch the reader’s eye: a sculpted raptor looming over the entrance to an elegant English countryside retreat (The Brandenburg Hotel, by Pauline Glen Winslow); a man in a balaclava and crimson down jacket, stretching a garrote between his gloved fists (Random Killer, by Hugh Pentecost); a heavily ornamented doorknob leading to the site of a locked-room slaying (The Red House Mystery, the only whodunit penned by Winnie-the-Pooh creator A.A. Milne); and a “gorgeous blonde stripper” apparently being threatened at the curtained entrance to a nightclub (Spence at the Blue Bazaar, by Michael Allen). The front-cover jigsaw pieces tended to highlight significant or symbolic elements of the stern-side scenes, whether it be a pistol on a serving platter, a bloody key inserted into a set of handcuffs, a gent scurrying away from a corpse, or a death’s-head carved into a violin scroll.

Like too many other paperback producers, Dell was awfully stingy when it came to including illustrator credits within the pages of its titles—a practice it continued with the Murder Ink/Scene of the Crime releases. And the passage of time hasn’t made the task of identifying those artists any easier. Chuck Adams, who was a managing editor at Dell during the puzzleback era (and is now executive editor at Algonquin Books), laments that “very few” of the paintings Dell employed in this line were signed. Which means “it is likely going to be impossible to know who all those artists were,” Adams says, “unless the artist him- or herself decides to sell [their work] online.”

Nonetheless, through a modicum of cyber detection—inspired by the few artists’ autographs visible on the series’ back covers—I’ve identified three of the people who contributed their talents to these books: John Melo, who created the aft illustration for A Medium for Murder, but may be better known for his work in the science-fiction and horror fields; Richard Newton, who gave us the eerie imagery on Mignon Warner’s The Tarot Murders, in addition to the knife-wielding hand on the posterior of Robert Barnard’s Death on the High C’s; and Tom Hallman, responsible for both the still-life on the verso of Jane Langton’s The Minuteman Murder and the audiotape-draped Shakespeare bust decorating V.C. Clinton-Baddeley’s My Foe Outstretch’d Beneath the Tree, though he’s recognized as well for his horror and fantasy book art.

While the founding design format for these mystery paperbacks was noteworthy, Mecoy concedes that “having only the missing piece on the front cover was one of the series’ weaknesses—the books looked too much alike when displayed face-out on the shelves. It was strong at the outset but several years down the road, it was confusing for consumers.” A change was finally made starting with the October 1981 publication of Colin Watson’s Coffin Scarcely Used, the first of that author’s Flaxborough comic crime yarns (dating from 1958), but the 29th installment in Dell’s lineup. Rather than the majority of each illustration being relegated to the back, it was suddenly switched to the more traditional face of every new novel, with the puzzle pieces dispatched instead to the opposite façade.

Cosmetic adjustments alone, though, couldn’t save the Murder Ink/Scene of the Crime brand. Part of the problem derived from its being a line of books: its viability depended on consistent achievement, yet some fictionists sold better than others. “When one author underperformed,” Mecoy points out, “it could affect the whole line’s success for months, until another author dramatically overperformed. This effect was thrown into high relief … when we reprinted Martha Grimes’s first novel [The Man with a Load of Mischief] in 1984.” That work sold exceptionally well, and a decision was made to move Grimes out of the Murder Ink stable and onto Dell’s main paperback list, leaving Brener and Windfeldt’s project in peril. Mecoy says Dell “realized that stories of sophisticated amateur detectives in interesting milieus were becoming mainstays of the mainstream mystery market,” and that it made better sense to focus on promoting individual writers rather than trying to keep a whole paperback series afloat. The company ended its association with the two bookshop owners in the mid-’80s.

Over the succeeding decades, Murder Ink—once touted as “the first bookstore devoted to crime and detective fiction”—has shut its doors. So has Scene of the Crime, though Ruth Windfeldt continues to sell rare and out-of-print books on the Web. She can’t now recollect precisely how many works featured in the series she and Carol Brener labored over, but knows there was a minimum of 76, because that was the number of Richard Forrest’s The Death at Yew Corner, released under the Scene of the Crime label in September 1984. Bob Mecoy is no better at identifying the final book in the line. “All I remember,” he says, “is that both the ladies called to tell me that the problem was the other half of the series and that if I’d only get rid of her, then everything would be just ducky.”