Excerpted from Our Man Down in Havana (Pegasus Books, 2019).

__________________________________

Shooting of background scenes on Our Man in Havana began on Sunday, April 12, 1959 in Plaza Vieja, a cobblestoned square with chrome yellow façades, and former location for bartering and selling slaves. The New York Times described a band of roving musicians and assorted tropical fruits arranged neatly on a corner stand and a cart laden with colorful local flowers. It added, “Graham Greene stood under a crumbling archway, behind the camera, a Leica dangling from his neck, intently watching and occasionally recording the goings-on.” Meanwhile, Carol Reed directed in a light linen open-necked Cuban guayabera hanging loosely over his trousers. SIS’s man in the Caribbean Henry Hawthorne (played by Noël Coward) was dressed less fittingly for the ninety-plus-degree-Fahrenheit heat. He appeared rigid in a tight-fitting blue woolen suit and stiff white collar, topped with a homburg—the stereotypical and incongruous Englishman in the tropics, with an umbrella to boot.

Coward had composed and sung the classic 1930s ditty “Mad Dogs and Englishmen,” decrying those expatriates foolhardy enough to emerge under the oppressive midday sun in tropical foreign climes. Describing his work on set the next day, Coward wrote in his diary: “On Monday all I did was walk about the streets very fast watched by thousands of bewildered Cubans and surrounded, for protection only, by hirsute armed policemen.”

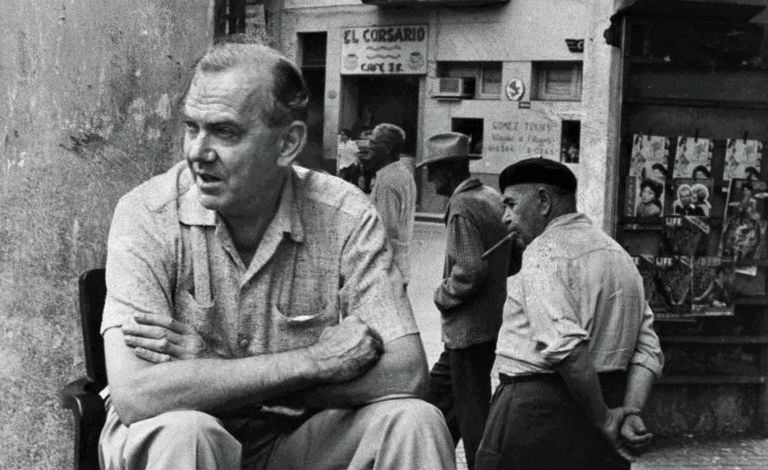

Greene in Havana during filming. Above, Hemingway with Alec Guinness and Noel Coward during filming.

Greene in Havana during filming. Above, Hemingway with Alec Guinness and Noel Coward during filming.

On Tuesday, April 14, the crew filmed a key scene in Sloppy Joe’s at the corner of Zulueta and Ánimas. Long-term Havana resident Ernest Hemingway dropped by to witness proceedings and chat with old friend Noël Coward between takes. Jay Mallin recalls introducing Hemingway to Greene at Sloppy Joe’s bar. However, despite their shared depressive natures and predilection for the world’s war zones as foreign correspondents, the visiting Englishman and the Havana-residing American did not hit it off. As Mallin relates, “it was perfunctory; they didn’t like each other.” According to Ted Scott’s “Interesting if True” column, Hemingway wore only a “beard, shorts and sports shirt” and merely said “Howdy” to Greene. The Englishman did not attend Hemingway’s cocktail party later that day at his San Francisco de Paula home.

Also in Greene’s absence, Coward described how a car whisked some of them off at lunchtime after shooting at Sloppy Joe’s to meet “the famous Fidel Castro.” After waiting for more than an hour, they gave up on their host. Coward reportedly mouthed “mañana” to a local official as they departed. As for the gathering at Hemingway’s home, he described everybody getting “thoroughly pissed.” His location shooting and five-night stay were now over, and he flew off to New York the next day feeling “very peculiar.”

Both drank and chased women, but the American’s all-action physicality was the polar opposite of Greene’s awkward impracticality.One can speculate as to reasons for the frosty Greene/Hemingway encounter. They had a lot in common, but their personalities were so different. Both drank and chased women, but the American’s all-action physicality was the polar opposite of Greene’s awkward impracticality. For example, both had spent time in Africa, but Greene would never dream of hunting big game as trophies and adorning his home’s walls with them. Wartime intelligence work was another experience they both shared, but again, it took a completely different form. As opposed to Greene’s largely office-bound work in Sierra Leone and London, Hemingway had assembled a motley international crew—the Crook Factory—to hunt down prowling Nazi U-boats in Caribbean waters, adapting his Pilar fishing boat with light arms for the enterprise. Still, the two-year-long escapade, endorsed by the U.S. ambassador in Havana from late 1942, turned into a lark and achieved next to nothing.

Professional jealousy could be part of the explanation for their brief meeting. Hemingway had won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954, while his English rival was never to receive the coveted prize. But the men supposedly had a more personal connection as well. According to an improbable story, during the Spanish Civil War, Claud Cockburn came across a scene where Hemingway identified a tall man in glasses as an enemy spy. The man was identified as Herbert Greene, Graham Greene’s older brother. Cockburn allegedly exclaimed, “Don’t shoot him, he’s my headmaster’s eldest son.” Still, if the story is true, it is unlikely that Greene harbored any ill feeling toward Hemingway for threatening to kill his troublesome brother. Had he shot Herbert, he might have saved the Greene family a lot of later bother.

Greene possibly resented Hemingway’s recent criticism of him in an interview with George Plimpton, published by the Paris Review in spring 1958. Despite Papa’s reluctance to explore his inspiration for writing during the whole interview, Plimpton pursued the question and proposed a nameless author’s idea that a writer “only deals with one or two ideas throughout his work.” After Hemingway had dismissed the proposition as too simplistic, the interviewer named the source as Greene. Pressed again, Hemingway contended a good writer’s most essential gift was “a built-in, shock-proof, shit detector.”

We can turn to well-connected American actress-turned-writer Elaine Dundy for Hemingway’s forthright take on Greene. Both she and her husband, Kenneth Tynan, were friends with “Hem” and had indulged a mutual interest in bullfighting alongside him in Spain. After downing some potent double daiquiris at the Floridita in April 1959, the couple dined at his home up in the hills, where the boorish American took aim at fellow writers. He gave Greene both barrels, accusing the English interloper of spending a mere ten days in Havana and writing a book that confused the city’s street names and buildings. Furthermore, the Englishman had then tried to deflect criticism by calling Our Man in Havana an “entertainment.” Greene had produced some good work, he said, “but now he’s a whore with a crucifix over his bed.”

Papa had at least paid the guilt-ridden Catholic the tribute of reading his Havana novel, even if he miscalculated his days spent in the city. It is true Greene had confused a few street names, using the formal Avenida de Maceo (instead of the informal Malecón), misspelling Virdudes (instead of Virtudes), and even giving the same hotel room two different numbers (both 510 and 501). In Dundy’s opinion, the fact that his rival’s new novel was a success, with its film version then in production on Havana’s streets, “may not have improved Hemingway’s temper.”

We might have never known the reasons for Greene’s reticence during his brief meeting with Hemingway, save for a diary entry from a later visit to Cuba in 1963. Pondering Sloppy Joe’s, where Hawthorne recruits Wormold in Our Man in Havana, he scribbled to himself, “Hemingway came to see the filming—we shook hands & exchanged wry glances: I was muscling in to his territory.” The annotation pointed to his scorn for Hemingway’s exaggerated machismo and confirmed the mutual feeling that Greene was trespassing on Papa’s literary patch.

***

Excerpted from Our Man Down in Havana by Christopher Hull, published by Pegasus Books. Reprinted with permission. All other rights reserved.