When I was a little girl my favorite place in my grandparent’s house was my grandmother’s closet. As an executive in the credit department at the newly-opened Resort’s Casino Atlantic City, my grandmother’s wardrobe was the stuff of fantasy, the perfect storm of 1980s high maximalism and gambling-mecca glitz. I spent these visits studying her suit jackets with their stiff shoulder pads and matching skirts, gently fingering the sequined and beaded dresses that shined even in the dim light. Racks of dangle earrings, stacks of bangles, and piles of candy-colored necklaces crowded the tops of her bureau. The piece de resistance of it all was the floor-length mink coat that was a gift from a client who worked as a furrier in Manhattan. Sometimes she gave me small things of hers to take home: clip-on earrings, petite fur stoles with pink silk linings, which I took to wearing over my nightgowns as I fantasized about the time when my life would become so significant and full as to necessitate such a varied and well-appointed wardrobe of my own.

These fantasies coincided with a singular time for Atlantic City, which was enjoying a fit of prosperity and expansion after the referendum legalizing casino gambling was passed in the late 70s. The faded resort had been reborn as a place that blazed with neon and shimmered with crystal chandeliers, its shoreline remade as the last crumbling Victorian hotels were replaced by glass and concrete monoliths. Sleek black stretch limos sailed along the Atlantic City Expressway, toward these new casinos and all that they offered: increased fortune, decadent meals, beautiful company. The city even seemed to reclaim an air of respectability that was reminiscent of its Victorian heyday: when Resorts first opened its doors in 1978, male guests were not allowed inside unless they wore a suit jacket.

These fantasies coincided with a singular time for Atlantic City, which was enjoying a fit of prosperity and expansion after the referendum legalizing casino gambling was passed in the late 70s.This infusion of investment couldn’t have come soon enough. “I have never, anywhere, seen so many broken windows,” John McPhee wrote of pre-gaming Atlantic City in his 1972 New Yorker essay “The Search for Marvin Gardens.” McPhee describes a place that was disorienting in its decrepitude, completely devoid of the tidy, cheerful order of the Monopoly game board that is modeled after it. But when gambling was legalized, the city swelled with a sense of promise. It drew world-famous musical acts like the Rolling Stones and even surpassed even Las Vegas as the de facto boxing capital of the United States. As a part of the hiring boon that came with this increased prosperity, my grandmother secured an entry-level job at Resorts in her fifties after raising six children with my electrician grandfather, eventually moving up the ranks of the Credit department and building a Rolodex of adoring clients, like her furrier, who lavished beautiful gifts and expensive dinners upon her.

As a child I was already compulsive about forming narratives, and I think what obsessed me the most about my grandmother’s wardrobe was the larger story I sensed behind these clothes and jewelry, the stacks of shoeboxes with colorful pumps nestled inside. These clothes told me not just who my grandmother was—a woman who found professional success late in life and who treated herself to a wardrobe that celebrated that success—but also implied a story about Atlantic City, its promise and capacity to raise up and reward those willing to work hard.

But by the time I was hired in my own entry-level casino job, the tide had turned again, and the city looked more and more like the disintegrating seascape that McPhee described. I worked as a receptionist at one of the casinos during my summers off from college, and quickly felt dulled and worn down by the malaise that now characterized everything around me. I spent my lunch breaks wandering the halls, treading the faded Florentine carpets and studying my surroundings through a haze of secondhand smoke. Cocktail waitresses served cheap drinks served in plastic cups to customers parked in front of slot machines in sweatpants, fanny packs slung around their waists. All of the buildings, once so shiny and grand with their mirrored facades and staggering towers, simply looked dated and in need of a good power wash. Even the iconic boardwalk hadn’t been spared: it was pocked by empty storefronts and populated by feral cats.

My own Atlantic City work wardrobe was so different than my grandmother’s beads and sequins, and tended, perhaps appropriately, toward the funereal: I was allowed to wear what I wanted for my shifts, so long as it was black. There were few limos idling at the curbs, no suit jackets, certainly no floor-length mink coats. The narrative I intuited from looking through my grandmother’s closet all those years ago had swerved dramatically, and I learned what was perhaps the true story at the heart of a gambling town, which is that good luck almost never holds. This lesson was playing out on a broad scale, too, as the entire country limped through a massive recession, one which hit Atlantic City particularly hard and from which it would never really recover. By 2016 five of its casinos—nearly half—would close their doors.

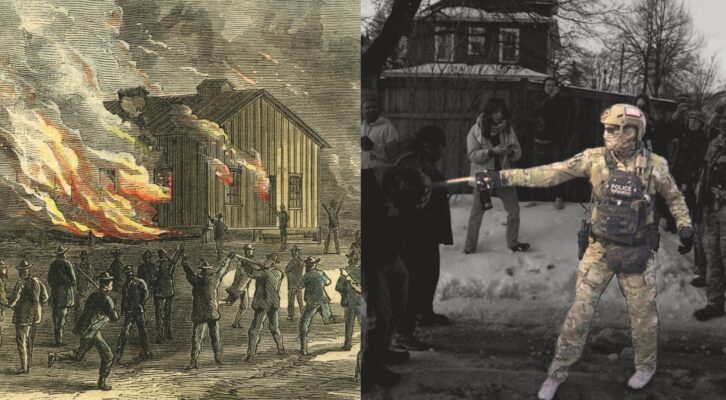

Atlantic City is nothing if not a town with a perpetual ability to reinvent itself.I wrote a novel set in Atlantic City in part because I wanted to explore what happens when a town that has once been considered an escape to so many, and emblematic of so many dreams, becomes a trap? A nightmare? I graduated from college, moved to New York, got a publishing job, and left my receptionist days—and my girlhood fantasies of a glamorous Atlantic City life—behind. But the story of Atlantic City is bigger than me, and there is something much more sinister in its decline. For those who remain tenuously employed by the casinos, there is no room to move up and ahead, and no safety net below. Add in an insidious opioid epidemic, an uptick in gang activity and violent crime, like the murders that inspired my book, and this decline is not only sad, but increasingly dangerous.

Despite all of this adversity, I try to remain hopeful: Atlantic City is nothing if not a town with a perpetual ability to reinvent itself. It has been a wholesome Victorian resort, a bootlegger’s Prohibition paradise, a soldier’s training camp during World War II, a 1950s family resort, and yes, the glitzy haven that I first knew as a little girl. A local college has just built dorms on the boardwalk that overlook the ocean. An artisanal chocolatier, the kind you’d expect to find in bespoke-obsessed Brooklyn, has recently taken up residence on Tennessee Avenue. What had been the Trump Taj Mahal was finally bought out by the Hard Rock and reopened after being shuttered and emptied out in a liquidation sale years ago.

And though I’ve come to terms with the fact that my life will probably not necessitate the kind of beautiful and elaborate wardrobe that my grandmother had, I still hang on to some of the pieces she gave me, those relics of another time, of another vanished version of Atlantic City. My favorite is a triple-strand necklace made up of graduated pearls that range from the size of marbles to the size of jawbreakers. In an era that favors the understated and minimal, this necklace demands attention in a way that is unlike anything else I own. I’ve taken to wearing it any time I need to feel powerful and bold. It also serves as a reminder of who and where I come from: a place that contains multitudes, and a line of women who found ways to build their lives—and their wardrobes—with unmistakable passion and verve.