The first time I ever saw one of my books on a “best of crime fiction” list, I felt sure that someone had missed an important piece of information. I wasn’t sure if it was me or the writer of that list. In my mind, “crime fiction” was exclusively written about crime and criminals from the perspective of detectives trying to thwart the criminals and their crimes. I’d grown up on Dell Shannon and Ed McBain novels I got from my grandfather, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and G.K. Chesterton books from the library. A child of the 70s and 80s, I’d been exposed to an endless stream of cop TV show—Adam-12, Kojak, Hill Street Blues, Cagney & Lacey.

The problem for me was that none of these stories aligned with what I’d been taught about the police or detectives. My first lesson from my father was never to trust the police. This isn’t too surprising, when you consider that my father has a long history of criminal behavior and incarceration. Even my grandfather, who was a law-abiding citizen, cautioned me about the police. While other kids at school were learning to call 911 in case of an emergency, I was learning that the police were not necessarily there to help people like us, people with a “history” with law enforcement.

As I grew older, I learned that being wary of the police wasn’t just my family’s rule. I learned that for so many people—Black people, homeless people, desperate people—the police weren’t there to protect and serve them, either. At the same time, I started paying closer attention to the way fictional cops and detectives are portrayed as flawed heroes, even when their behavior is downright criminal. The “good guys” are shown conducting illegal searches, falsifying reports, and even torturing suspects to get confessions. Often the perpetrator is a murderer, or even a serial killer, like in Dirty Harry, so the audience can feel more comfortable with their rights being violated.

Meanwhile, the more I knew about the world, the less comfortable I was with that crime fiction trope. If the police concocted evidence against a murderer, why wouldn’t they concoct evidence against someone else, maybe even someone innocent? After all, despite my father’s actual crimes, he’d also been set up a few times by small town police who viewed him as a convenient scapegoat. I couldn’t help but grow up to believe that there were other perspectives on crime fiction. When I began writing the stories I wanted to tell, I frequently, and without intending to, ended up telling stories about the mundane and sometimes necessary crimes of poor Midwesterners.

As natural as it was to me to write from a place of sympathy for a variety of petty criminals, many of those early stories were critiqued or rejected for those crimes. But why is she a prostitute? Why is there this whole check kiting subplot? Couldn’t this character have been framed instead of being an actual criminal? It would make him more sympathetic. You can see how I got the idea that I wasn’t writing crime fiction, because so many people told me I was writing about crime from the wrong angle.

After the first time I saw one of my novels on a crime fiction list, I thought about another book I’d read alongside my grandfather: Les Misérables. It’s literature. It’s a musical. It’s iconic. It’s also crime fiction in its own way, and in a way I understood instinctively when I read it as a teenager. The main character is a criminal. The antagonist is a policeman. In describing it, Victor Hugo said, “Social problems go beyond frontiers. Humankind’s wounds, those huge sores that litter the world, do not stop at the blue and red lines drawn on maps. Wherever men go in ignorance or despair, wherever women sell themselves for bread, wherever children lack a book to learn from or a warm hearth, Les Misérables knocks at the door and says, Open up, I am here for you.”

Hugo saw his novel as both a tale of redemption, but also as a discourse on the source of nearly all social ills in the 19th Century: poverty. Nearly two hundred years later, that’s still the cause of a lot of crime. If your choices are crime or starvation, crime is the better alternative. If you have to steal bread to keep children from starving to death, like Jean Valjean, crime is a more moral choice. That was another of my grandfather’s lessons: legality and morality are not the same thing.

Your average drug dealer doesn’t get into the business for fun, or because they’re a bad person, but for the same reason my bootlegging ancestors ran alcohol across state lines a hundred years ago. That illegal substance and the sale of it kept families from starving to death. It helped families crawl up out of poverty and find more genteel ways to make a living. With Prohibition nearly a hundred years in the past, bootlegging is often romanticized now. Bootleggers are loable rogues breaking what now seems like a silly law. Contemporary drug smuggling, on the other hand, despite its similarity to bootlegging, still shows up in crime fiction and film, often with the dealer or mule vilified for their crimes.

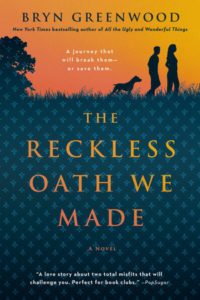

When I started work on my most recent novel The Reckless Oath We Made, I knew many readers would be upset to discover that my main character was a drug mule and a sometime sex worker. Had she been a bootlegger, perhaps the veil of the romantic past would have made people judge her less harshly, but even the kindest readers tend to view a character involved in the sale of illegal drugs as morally ambivalent.

Police procedurals are meant to comfort us with the notion that the law is there to protect good people from bad people. They don’t often deal with the reality that many people who commit crimes aren’t so much bad as they are lacking in better options. Plenty of acts are only criminalized to keep poor people poor. Drug possession and prostitution are among those crimes.

A low income person is far more likely to be arrested for drug possession than someone with a higher income. As for sex work, solicitation is a crime committed almost exclusively by poor people. Once arrested, a low income person is more likely to remain in the prison system for lack of access to bail money, skilled attorneys, and other resources. After release from prison, a poor person is less likely to find legal employment, may still have fines to be paid related to their previous arrest, and so is far more likely to commit another crime and be re-arrested. All that combines to keep them locked into a cycle of crime.

Once I started thinking of my stories as reflections on that all too common experience, I became excited at the idea of my writing being classified as crime fiction. The narrow confines of the genre I understood as a child are much broader, and in being broad, are more important. If a fiction genre can help us think about and discuss such serious social issues as law enforcement and the prison industrial complex, that’s a genre I want to be in.

*