I have murderous thoughts. If you’ve angered me, I’ve probably imagined shoving you down a flight of stairs, driving an icepick into your eye, bashing your skull with a statuette, dripping arsenic into your Old Fashioned, or holding a pillow over your face as you impotently flail, the lights behind your eyes popping like firecrackers and dropping as cinders into the black. I might have thought of shooting with you a gun, because I’m sometimes simple and straightforward.

I am a violent woman. I am also, alas, a moral woman. This is a conflict, but the conflict between being a human with a will to rampage and one with a deep moral compass is secondary. The real conflict is that of being a female human loaded with all the cultural trappings of femininity and being a person with an anger issue. Anger in a man is acceptable. Anger from a woman is frightening, alarming, even destabilizing. Boys will be boys, and men will be violent, but there’s little societal room to indulge, excuse, or even express those feelings in women.

These conflicts have drawn me to true crime. My guilty obsession is Snapped, the Oxygen show about female murderers, most of whom are terrible at killing. I like women who kill. I want to hug them and tell them that I understand because I truly do, yet this wildly popular outlet vexes me. True crime, as writers like Alice Bolin and Sarah Weinman have noted, is a deeply problematic genre. Lurid and alluring, true crime allows us to spectate without repercussions, reveling in the always grisly, often exploitative, frequently racist narratives that usually erase the murdered persons at the story’s center while celebrating the murderer, law enforcement, or both.

Thus, I have tried to turn to reading or watching fictionalized crime to soothe my savage beast, but that too is often a bust. Whether you’re talking Twin Peaks, James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia, Stieg Larsson’s Millennial Trilogy, or the majority of crime fiction with the word “Girl” in the title, most murder fiction centers on the bodies of dead women (or dead girls, sometimes dead children, often dead sex workers). As a reading and viewing culture, we have grown so used to men who used to love her but had to kill her that, with a few notable exceptions, we readers, writers, viewers, and producers of crime fiction cease to notice the feminized body count.

***

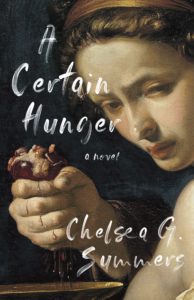

I wrote my first novel, A Certain Hunger, as I rounded the bend into my fifties. Approaching my book, the story of a cannibalistic serial killer who murders and eats her ex-lovers, I wanted to take aim at traditional crime fiction, as well as give voice to my own murderous rage. Early in the writing process, I revisited Brett Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, the archetypal ironically distant misogynist crime novel. While Mary Harron’s film, released in 2000, makes Patrick Bateman’s killing spree a possible fantasy, shifting the focus from Bateman’s bloodlust to his all-consuming vanity, the book reads red with women’s blood, all possible ambiguity pushed to the background. Ellis’s novel, in all its hyper-stylized glory, was an inspiration for my own, as much a wish-fulfillment fantasy and as full a satire as American Psycho. But in my book, the dead are male, and the murderer is not.

If you care about living, breathing women—and I do—fictional murder is a feminist issue. At the issue’s base sit the layers and layers of casually killed women, the narratives predicated on the wispiest chalk outlines of feminine bodies, those female characters who are hardly given time and words to establish their own identities before they’re sacrificed to the story. The message here is that women’s lives don’t have value in and of themselves; they’re better dead than alive, their deaths important only in that they’re pivotal to the detective, the storyline, and the climax. It’s not a good look.

Behind the bodies of the dead women who center murder fiction, there is always a signifier of something else. She’s someone’s daughter, sister, mother, wife, or friend; her murder is the marker of someone else’s pain and loss. If she’s young, she’s innocent; if she’s ripe, she’s despoiled. If she’s a virgin, she’s a symbol of cleanliness and purity; if she’s sexually experienced, she’s a morality tale. If she’s queer, if she’s trans, if she’s Black, if she’s disabled, or if she’s aged, then she’s an odd loss, a place-marker of the writer’s often questionable politics. The murdered bodies of fictional men rarely come loaded with the same cultural messages, because “male” remains the default setting for human experience.

“A beautiful girl dies, and a man feels bad about it,” is how writer Laura Lippman sums up crime fiction’s formulaic nature. Formulas are nice. They make us feel safe, sometimes even cozy. But the very nature of fiction invites risks. So, I have to ask, what if the man dies and the beautiful girl doesn’t feel bad about killing him? And what if she’s not a girl but a woman? And what if she’s not even that beautiful?

When murderous fictions tell the tales of women killers, they can go beyond merely offering payback. They can grant release to the angry, gifting rage-filled female readers with the freedom of identification. They can offer an imagined glimpse into the minds of women who kill, a stereotype much limited to sultry black widows, whippet-thighed noir heroines, frenzied revenge stalkers, and bad mothers. They can provide twisted minds like mine with a safe place to vent their blood-soaked musings. And they can embellish the textured, embroidered, and layered fabric of female experience with a fine, feminist arterial spray.

Books like Oyinkan Braithwaite’s My Sister, the Serial Killer, Amy Gentry’s Last Woman Standing, or Leila Slimani’s The Perfect Nanny flip expected scripts on fictional murders, calling into question the validity of the tried-and-true formula. Moreover, these books model the possibilities of crime fiction, opening up the genre to female rage, experience, humor, and bodily grossness.

Bloody good fiction can be a feminist act. It has the power to overturn the prevailing murder model and to provide fictional freedom for people of all genders. There’s slippery joy to be found in letting your inner serial killer loose on the page. Patrick Bateman, Hannibal Lecter, and Dexter have hogged the fun long enough. It’s time for them to move aside and make room for some new blood.