When it comes to fiction, some states punch above their weight, contributing more to the canon of American literature than their population totals would suggest likely. It might be something in the water, or a culture of storytelling. Minnesota is one of those states, and few writers from that fair land have made it so much their own as William Kent Krueger.

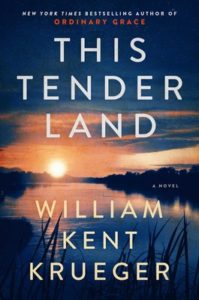

In his much admired Cork O’Connor series, Krueger follows the life and investigations of a mixed Irish-Ojibwe ex-sheriff working tracts of northern Minnesota bordering on reservations, county lines, and the kind of backcountry that hides its secrets well. That series is now in its seventeenth installment (last year’s Desolation Mountain), but throughout that time the author has written a number of remarkable standalone novels, stories that seem always to get more ambitious in their scope and craft. Most recently, Krueger told a sweeping story of four orphans escaping from the The Lincoln Indian Training School and venturing down the Mississippi River. The four share a deep bond, a traumatic past, and an urge toward the river’s freedoms. Krueger captures a rich tableau of Depression Era Minnesota and manages through this complex, searching tale, to tell a bigger story about the nation’s past. I caught up with Krueger to talk with him about his home state, Mississippi River literature, and This Tender Land.

This Tender Land begins at The Lincoln School for Native American children. Even calling it a “school” feels like a cruel euphemism. The physical, spiritual, and cultural abuse is startling. With families torn apart, children kept in terrible conditions, this seems like an important part of our history to revisit now. What prompted you to explore this world in fiction? Was it a piece of history that’s been calling to you?

WKK: Because my long-running Cork O’Connor mystery series deals significantly with the culture and history of the Anishinaabe, I’ve been aware for a very long time of the existence of the boarding schools, but until I chose to set the opening section of This Tender Land in the fictional Lincoln Indian Training School and did my research, I lacked a full understanding of the true horror of that environment. It’s yet another in a long litany of mistreatment of Native Americans since our European ancestors first arrived on this continent. We’ve looked away from this tarnished past far too long. An awareness of the trauma that occurred in these institutions and of how that trauma continues to haunt the Native community today is important in any understanding of the continuing struggle to heal. In This Tender Land, I wanted the Four Vagabonds to be running from the worst of horrors, and I couldn’t imagine anything worse than one of these boarding schools.

When your novel sends young people on a journey down the Mississippi River, Twain, in particular Huckleberry Finn, is obviously going to come to mind. Were you wrestling with that legacy as you worked on This Tender Land? That’s a tough standard to meet, I imagine. Then again, maybe it’s an inspiration?

WKK: There was never any wrestling with Twain’s legacy. I didn’t set out to upstage Huckleberry Finn. But that great American classic was certainly the seminal inspiration. I’d wanted for a good long while to write an updated version of the story. I can’t really say why. The idea simply appealed to me, constantly nibbling at the edges of my thinking. I took a couple of whacks at the story over the years, but it never jelled, never felt right. Then I spent two years at work on a manuscript for a different story, which ultimately I chose not to publish. That was a bleak period. But when I came out of it, the tale for This Tender Land pretty much presented itself in a way that I knew I could write it. So I launched into the project, and this time I never looked back.

The setting of this book—the Midwest, northern Mississippi River region during the Depression—plays such an important role, and you capture the world so vividly. Was this a period you’ve been wanting to write for a long while? It had the feeling of a place that had been not just researched, but richly imagined.

WKK: Part of what came together for me when I emerged from the bleak period I mentioned earlier was a clear sense of the time frame for the story. In my earlier attempts, the setting had been more contemporary. But as the elements came together and I understood a number of the themes I wanted to deal with—What is home? What is family? What is God? How can the human heart be capable of both great cruelty and great compassion?—the Depression seemed the perfect setting. And because I’m a child of Midwest, it would, of course, be a story set in the heartland in that time of tremendous privation.

This is a frontier story unlike any I’ve read, yet it shares certain key traits: that search for a new home, the improvised families, the bonds forged on the road. Do you see this book as being part of a tradition of journey/exodus stories?

WKK: Every fictional story is about a journey. It’s simply more evident in some than in others. The picaresque nature of stories that are openly about a journey—Huckleberry Finn, The Odyssey, On the Road, Grapes of Wrath—offers the opportunity for numerous and varied encounters, lots of lessons learned, a cast of memorable, larger-than-life characters. The canvas is enormous and the colors on the palette plentiful. Really, a tale of this kind is a storyteller’s dream.

This isn’t quite a crime novel, but I couldn’t help but thinking, as I moved through the story, that death was all around and that your characters had to become well acquainted with it. Did that consistent presence—of death—connect this book to crime fiction for you, or are they wholly different styles, different exercises?

WKK: For me, the deaths per se aren’t what connects the story to the crime genre. It’s the crimes themselves. There’s murder, kidnapping, bootlegging, extortion in This Tender Land, to name just a few. The novel is firmly in the crime genre. But it’s also about a great deal more than the crimes that occur. I think every good novel in our genre is about more than just the crime or the mystery. The structure for This Tender Land is different from many crime novels, more episodic, less dependent on assembling pieces of the puzzle. As a result, the writing was also a very different experience for me from that which generally characterizes the writing of a Cork O’Connor story.

Do you see any great affinities between the Cork O’Connor series and your standalone novels? Some preoccupations or themes you return to again and again, no matter the book?

WKK: I see many shared elements in all the stories I’ve written, and probably those I write going forward will share them as well. The Cork O’Connor stories often contain an undercurrent that deals with the spiritual journey, as does This Tender Land. They all deal with the search for justice, for a place of compassion and forgiveness. The characters are flawed human beings trying to find their way in a confusing world. And all the stories are aimed at the reader’s heart, which ought to be the target of every good story.