New York City is famous for a lot of things, but both “dining” and “crime” have to be toward the top of the list.

And often, the two are intertwined. Food and crime are, after all, junctions where passions collide—whether it’s a livelihood at stake, or a war over a stolen recipe, or just a chance to catch someone out in public at a restaurant. Sometimes, you don’t know which meal is going to be your last.

In fact, you could put together a lengthy and macabre walking tour of some of the city’s biggest “hits”—and I don’t mean of the restaurant review variety. There’d be plenty to eat along the way, too, as a couple of these joints are still open…

Rao’s

Rao’s in Harlem is one of the most famous red-sauce restaurants in New York City. Opened in 1896, it now boasts locations in Las Vegas and Los Angeles. Reservations at the original location are famously hard to come by—all the tables are “reserved” by regulars on an ongoing basis, so if you want to get in, you better know somebody.

It was also the site of a dispute turned deadly. Three days before Christmas in 2003, co-owner Frank Pellegrino invited an up-and-coming Broadway actress to sing “Don’t Rain on My Parade” to revelers. Albert Circelli, an alleged associate in the Lucchese crime family, began to heckle her, so 67-year-old Louis “Louie Lump Lump” Barone, another mob type, shushed him.

Their altercation came to a head, and Barone pulled out a .38-caliber revolver, shot and killed Circelli, and then fired a second round that hit a bystander in the foot. Barone dropped the gun and strolled outside—straight into two cops.

L&B Spumoni Gardens

To my mind, the squares at L&B in Bensonhurst are among the best slices of pizza in New York City. They’re thick, a little doughy, with the sauce over the mozz and sprinkled with parm. An atypical pizza construction for sure, and one that nearly sparked a mob war.

The story goes like this: Francis Guerra, an alleged Columbo associate whose family helped run L&B, found out that an alleged Bonanno member, Eugene Lombardo, opened a joint on Staten Island with a similar square slice. Lombardo’s sons had worked at L&B, so Guerra figured they stole the recipe. Threats were made. A sit-down was called, wherein the Colombo family demanded a cut. Supposedly things got settled.

Later, in 2016, co-owner Louis Barbati was fatally shot outside his home in Dyker Heights. Barbati was carrying more than $15,000 in cash from the restaurant, and detectives initially thought it was a robbery gone wrong, since the money was left behind. They later arrested Andres Fernandez, a drug user from the neighborhood, for the execution-style hit. Though they suspect a mob link, Fernandez has refused to cooperate.

Umberto’s Clam House

In April 1972, Joe Gallo—a.k.a. “Crazy Joe”—entered the former location of Umberto’s Clam House on Mulberry Street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. He was there with his family and bodyguard to celebrate his 43rd birthday.

A rival gangster spotted him and sent in a team of hitmen to kill Gallo, who was shot several times and exchanged fire with the gunman before stumbling into the street. He was later declared dead at a local hospital. Questions remain about the exact nature of the beef—Gallo may have been pushing into nightclubs controlled by rival mobsters.

Umberto’s is on its third location, not too far from the original, but it’s still a popular spot for lookie-loos fascinated with mob history. Gallo’s killing sent ripples through the Colombo family, and not too long after, resulted in a tragic case of mistaken identity…

Neapolitan Noodle Restaurant

August 1972. Sheldon Epstein, from New Rochelle, and Max Tekelch, of Woodmere, LI, sidled up to the bar at the restaurant on E 79th, along with their spouses and two pals. A man in a shoulder-length black wig ordered a scotch and water and took a few sips before standing, pulling out two .38-caliber revolvers, and opening fire on the group.

Epstein and Tekelch were both killed, and their companions were wounded. The shooter was a hitman from Las Vegas. The victims were old friends meeting to celebrate a daughter’s wedding engagement—who had taken seats vacated moments earlier by four Colombo crime family gangsters marked for death by Gallo loyalists.

It was one of the few times in the mob’s history when innocent bystanders were killed in a hit gone wrong. The restaurant closed, and is now an Albanian mission.

Nuova Villa Tammaro Restaurant

In 1922, Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria escaped an assassination that earned him the nickname “The Man Who Can Dodge Bullets.” By the end of the 1920s, he was one of the most powerful Mafia bosses in the city, and his favorite restaurant was Nuovoa Villa Tammaro in Coney Island.

One evening in April 1931, he was at the restaurant, playing cards and drinking with Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Luciano excused himself to use the restroom—and several gunmen appeared, opening fire. Luciano’s power grab was successful. Masseria was found dead on the ground with a bloody ace of spades clenched in his right hand.

Masseria’s murder is a major event in Mafia lore, but the site of the crime is now a nondescript brick building, home to a smoked fish company.

Sparks Steak House

“Big Paul” Castellano, head of the Gambino family, was known as the Howard Hughes of the mob world—he rarely left his Staten Island mansion in the tony Todt Hill neighborhood. And it was for good reason, because on one of the rare nights that he did leave, for a meeting with associates at the Midtown steakhouse in December 1985, he was gunned down as he stepped out of his car.

A group of hitmen was waiting near the restaurant’s entrance, and as Castellano exited his black Lincoln Continental, the gunmen shot and killed him and his bodyguard, Thomas Bilotti, under orders of infamous mob boss John Gotti.

Gotti, who sat in a nearby car to observe the hit, was feuding with Castellano over drugs—Castellano didn’t want his family involved in trafficking, while Gotti was making good money dealing heroin. A few months after the hit, Gotti was able to win over fellow capos to become the new boss of the Gambino family. Sparks is still open—and still highly rated by diners.

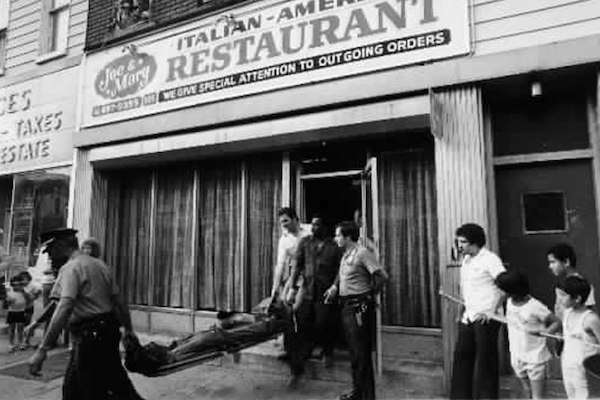

Joe and Mary’s Italian-American Restaurant

Carmillo “Carmine” Galante was nicknamed “Lilo”—Italian slang for “cigar”—was rarely seen without a stogie. He was also suspected of more than 80 murders and ran a very successful heroin operation, eventually rising to head the Bonanno crime family.

But he made himself a target when he started planning to knock off rivals so he could be named capo di tutt’i capi—“boss of all bosses”. In July 1979, while dining with associates on the patio of Joe and Mary’s, three ski-masked men opened fire on them.

Galante’s Sicilian bodyguards, Baldassare Amato and Cesare Bonventre made it out curiously unscathed. And the killing resulted in one of the most famous photographs in Mafia crime scene history. It showed Gigante, his eye shot out, crumpled on the ground, a cigar still in his mouth. The Bushwick restaurant later closed, become a Mexican restaurant, and currently appears to be vacant.

The 596 Club

The mob doesn’t have the market cornered on restaurant hits. At the corner of 43rd and 10th is Mr Biggs Bar & Grill, a standard Hell’s Kitchen pub with a macabre history. It was originally the The 596 Club, owned by Jimmy Coonan, leader of the notoriously violent Irish gang, the Westies.

And in 1977, it was the last place loan shark Ruby Stein saw, when he was lured there and shot dead by a Westies-hired hitman. Afterward, his body was dragged into the woman’s bathroom, where Coonan gave his crew an impromptu lesson on how to dismember a body. Stein’s various parts were dumped into the East River, but since Coonan neglected to pierce Stein’s lungs, his chest floated back to shore.

There are also legends of jars behind the bar that held severed fingers of people who’d tussled with the Westles, and reports of a night where gangsters rolled a severed head along the bar. It’s claimed the location is haunted.

Winnie’s Bar and Restaurant

In 1990, a turf war between rival Vietnamese and Chinese gang members ended in bloodshed at this infamous Chinatown dive.

Cops said the suspected assailants were members of the Canal Street Boys, a name adopted by a gang of ethnic Chinese from Vietnam. The two victims, Peter Wng, 20, and Dak Leong, 19. were said to be members of a Chinese gang, the Ghost Shadows. The Canal Street Boys had been operating for several years at that point, and cops said they were involved in extortion, robberies and several homicides.

Though the closing of Winnie’s, a popular karaoke spot, was widely-lamented amidst the city’s nightlife set, there were rumors last year that it might be reopened.

Dorrian’s Red Hand

In August 1986, 18-year-old Jennifer Levin was found battered and strangled in Central Park. Twenty-year-old Robert Chambers was arrested for the murder, having met Levin at Dorrian’s Red Hand, an Upper East Side sports bar with a reputation as a “meet market.”

Dubbed “the Preppie Killer” and charged with two counts of second-degree murder, he became a daily tabloid fixture. The headlines were unkind to Levin—in the Daily News: “How Jennifer Courted Death”—while Chambers was portrayed as a “preppie altar boy” with a “promising future.”

Chambers claimed Levin died during “rough sex” and the jury deadlocked. He pled guilty to a single charge of manslaughter, receiving a sentence of 5 to 15 years. Released in 2003, he was arrested a few years later for for selling drugs out of his apartment, and was sentenced to 19 years in jail. Dorrian’s is still open, and for a period of time was a popular hangout of former New York Yankee Derek Jeter.

Food trucks

Lest you think crime is confined to brick-and-mortar joints, New York City’s food truck scene is rife with falsified permits, parking spot disputes—and even bloodshed.

In 2009, the owners of the Street Sweets food truck told the New York Times they were: “threatened at the depot where they park the truck; cursed by a gyro vendor who said that he would set their truck on fire; told to stay off every corner in Midtown by ice cream truck drivers; and approached by countless others with advice—both friendly and menacing—on how to get along on the streets.”

The ice cream trucks are even more cutthroat. In 1969, a Mister Softee driver was kidnapped by rivals who blew up his truck. In 2004, a Softee-selling couple in their 60s were attacked by competitors who beat them nearly to death. In 2012, a frozen yogurt vendor accused Softee employees of snapping his brakes with a crowbar, and the founder of the Van Leeuwen ice cream company said he had gotten death threats from Softee drivers.