In the early hours of October 17, 1953 in Fairbanks, Alaska, businessman Cecil Wells, 50, was shot by a .380 caliber pistol while he slept. His wife Diane, 31, was badly beaten during what she told police was a two-man home invasion turned deadly.

A few days later, police got a tip-off that Diane was having an affair with Black musician Johnny Warren, and the investigation went in a different direction.

During research for The Alaskan Blonde: Sex, Secrets, and the Hollywood Story that Shocked America, my book reexamining the case, I expected to be quizzed about what I thought had happened that chilly morning.

Instead, the question I was repeatedly and incredulously asked was: “Why are you interested in this story?”

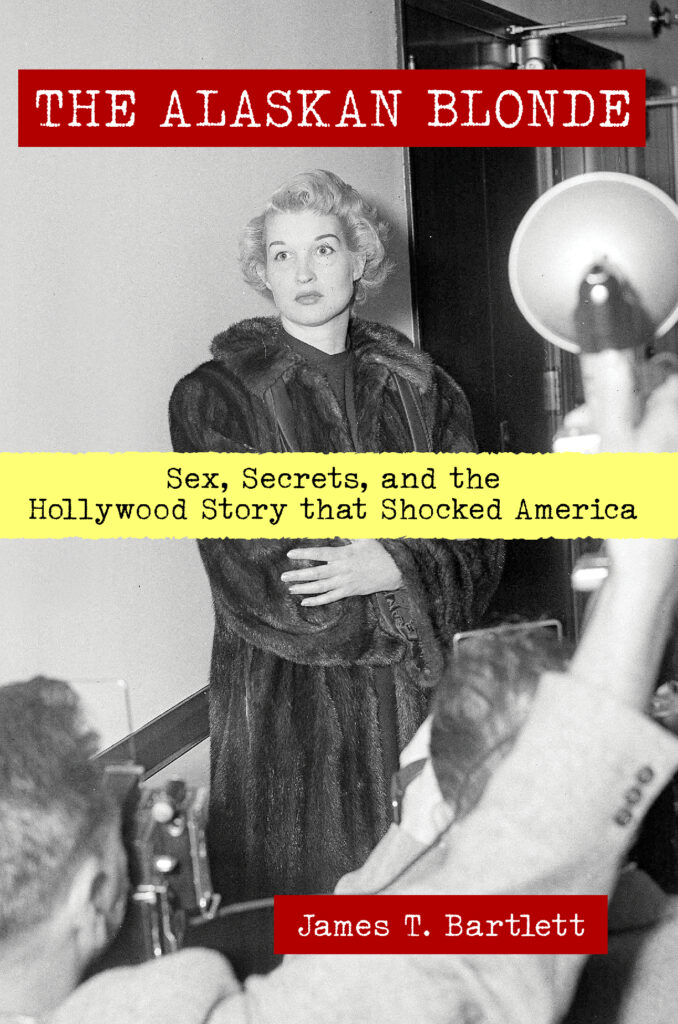

I first read about the murder in the Los Angeles Times archives. The black and white pictures of a Monroe-esque Diane being chased by paparazzi looked like the quintessential film noir, but then it became clear there was a very contemporary feel to the case.

Once it was revealed that Diane had been having “intimate relations” with another (Black) man, the story hit the headlines across the world.

Life, Newsweek, Jet and pulp magazines like Front Page Detective blazed it across their pages too, and the media frenzy that followed was, I thought, exactly what would happen today, only now it would conjure up instant judgment via Twitter, rather than black-and-white print.

In most true crime books, like Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me or Party Monster by James St. James, part of the appeal for readers is that the author discovers their family member, lover, or friend had committed a deadly act, or been living a lie.

There are intense survivor stories too, but it’s the untangling of the lie, or the path towards closure or overdue justice in narratives like Fatal Vision by Joe McGinnis, I’ll Be Gone in the Dark by Michelle McNamara and the recent, “My 25 Year Journey to Find a Killer,” by Jim Cosgrove, that feature a retrospective journey we want to take alongside them.

None of that applied to me. I had absolutely no connection to this murder case at all.

Firstly, I had been born in England nearly 20 years after the murder happened. True, I had been living in Los Angeles since 2004, but even so, all I knew about Alaska was that it was big, frozen, far away, and full of polar bears.

However, I found that precisely because I was a foreigner and outsider (literally, as most Alaskans call the contiguous 48 states “The Outside”), many of the people I interviewed quickly trusted me enough to talk to.

Having an English accent definitely helped break the ice, but I knew from the beginning that I couldn’t rely on science to crack this coldest of cold cases.

There was no physical evidence left at all, just the FBI file and police reports, and so I would have to rely on what people told me, and hope that they might generously share any aging documents or family photos they had in their cupboards or desk drawers.

When Diane and Johnny Warren were indicted for first-degree murder, US Marshal Frank Wirth was dispatched to Oakland, California, to extradite Johnny back to Fairbanks.

Wirth’s daughter sent me unpublished memoir pages in which he speculates about where the murder weapon ended up, and the package also included a water-damaged photograph of the pair – one in handcuffs, one with a cigar – laughing together.

It was a press photograph that, unsurprisingly, had never been published, yet Wirth had made sure he got a copy. The package also included a mugshot of William Colombany, the man Wirth strongly hinted publicly – and now, I knew, also in private – was the “Third Suspect.”

When I eventually located Colombany’s granddaughter, she told me that her mother would get angry even when his name was mentioned. From that point on, everything I told the granddaughter was information about a man she literally knew nothing about.

Theories about who committed the murder had lasted for decades, though almost everyone I spoke to had no idea what happened in the investigation, let alone in that 8th floor apartment in Fairbanks.

Back in 1953 it simply hadn’t been discussed (at least when children were present), and so I was particularly curious about Cecil and Diane’s son, Marquam.

Known as Mark, he was cruelly christened “The Murder Orphan” and the “The Millionaire Orphan” by the newspapers, as his father’s substantial fortune became his when he wasn’t yet four years old (though everyone agreed that in the end the lawyers got all the money).

Mercifully, Mark had been staying with his grandmother the night his father was killed, but to my disbelief, no one had any idea of his whereabouts since a sister of Cecil’s had been awarded custody and he had been whisked back to Alaska.

He was potentially the most crucial part of the puzzle, so when he quickly called me back and talked animatedly about the case, I momentarily dreamed that the book might write itself. But then I received a letter from him wishing me luck, but politely backing out of any further involvement,

Reaching out via Facebook and making countless cold calls, I found that a number of other children from Cecil and Diane’s various marriages, now in their 70s and 80s, were willing to have a conversation. I learned that Diane was estranged from the two daughters of her first marriage, and was given the phone numbers of some adult friends of the Wells’ who were still living.

Age may have taken its toll, but they were happy to revisit their memories and discuss something they felt had been swept under the carpet when Alaska gained its long-awaited statehood in 1959: it didn’t matter that it happened nearly 70 years ago.

Some of the children (and grandchildren) had connections to Cecil, Diane, or Johnny that were barely stronger than mine. They often had little to add, but were glad to hear from me nevertheless.

Private detectives worked the case throughout the 1950s, and the FBI kept the file open until after Statehood, but the later jailing of someone for their involvement in the Cecil Wells murder was a surprise to everyone I interviewed. Maybe it had been forgotten as quickly as Diane’s story unraveled, and the media had turned on the black-eyed victim they nicknamed “the most beautiful woman in Alaska.”

Occasionally I did feel like I was more of an intruder than a curious outsider, but overall, the experience made me think that several families all owned a copy of a dusty, battered, well-thumbed mystery novel that was missing several pages – including the ending.

After nearly five years of research, the new evidence I uncovered helped shape the final chapter of the book: October 17, 1953, which semi-fictionalizes that last morning in room 815.

***