Before Jack the Ripper, before The Devil in the White City’s H.H. Holmes, the world’s deadliest serial killer was the Canadian Doctor Thomas Neill Cream. The graduate of McGill Medical School murdered as many as ten people in Canada, the United States, and Britain between 1877 and 1892, escaping suspicion and even a life sentence in prison to kill, again and again. In this excerpt from The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer, published by Algonquin Books, author Dean Jobb follows Cream from the gates of an American prison to the streets of England, where the ruthless poisoner is about to unleash his wrath on the women of London.

Joliet, Illinois, July 1891

The iron door of the Illinois State Penitentiary in Joliet groaned open and spat a haggard-looking man into the world he had left almost a decade earlier. It was the final day of July 1891, a clear-sky Friday. High above the man’s head, atop the gray limestone walls of the penitentiary forty miles southwest of Chicago, men in blue coats toting Winchester rifles watched him walk away. If this had been an escape, a single guard could have pumped sixteen bullets into his back without reloading.

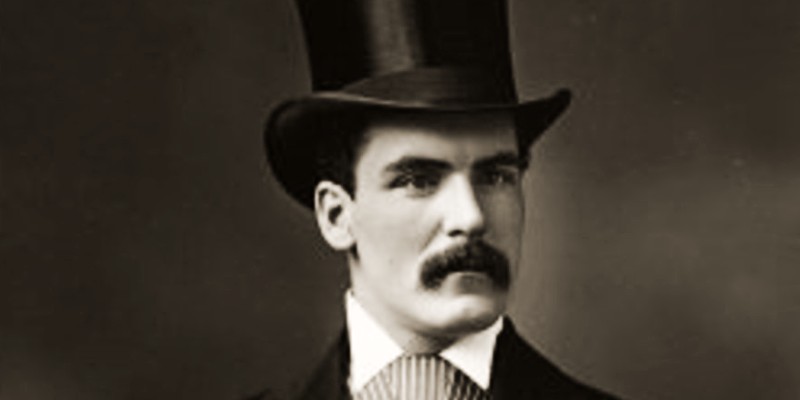

Thomas Neill Cream’s hollow cheeks and sharp-edged features were the legacy of years at hard labor and stints in the mind-crushing hell of solitary confinement. He had traded his zebra-striped prison uniform for a new suit—a modest gift, like the ten dollars in his pocket, from the State of Illinois. His few belongings were stuffed into a pillowcase. Prison staff stopped cutting an inmate’s hair in the weeks before release and the men could grow a mustache or beard, helping them blend in. But the practice had made little difference to Cream, who was almost completely bald. Besides, after marching day after day in lockstep with fellow inmates—pressed together, single file, inching along like a giant striped caterpillar—many walked with the shuffling gait that betrayed them as former inmates. “The stripes,” noted Joliet’s warden, Robert McClaughry, “show through his citizen’s clothes.”

Cream had been inside for nine years and 273 days. Chester Arthur had just become president, replacing the assassinated James Garfield, when he began serving a life sentence for murder in November 1881. Grover Cleveland had won and lost the presidency in the meantime and now Benjamin Harrison occupied the White House. People who peered into the eyepiece of a prototype of Edison’s kinetoscope, unveiled a few weeks earlier, were astounded to see moving images. In Springfield, Massachusetts, brothers Charles and J. Frank Duryea were tinkering with a prototype they called the “Motor Wagon”—America’s first gasoline-powered automobile.

Even crime fighting had changed during Cream’s confinement. A few years before his release, an array of odd-looking calipers and measuring sticks had arrived at Joliet. Calibrated in centimeters and millimeters—metric-system increments rarely used in the United States—the devices were designed to precisely record the size of specific parts of the body. This pioneering system of identifying criminals bore a name as strange and foreign as the tools it required: bertillonage.

The system, developed in France, was based on eleven measurements, including a person’s overall height, the width of the head, the dimensions of the ear, the size of the left foot and the forearm, and the length of the middle and ring fingers. While two men might be found to have the same-sized foot, the chances of multiple measurements being identical were remote, and the odds of finding two subjects with identical sets of all eleven measurements was estimated at one in more than four million. To make a misidentification even more unlikely, the subject’s face was photographed, and eye color and any tattoos or scars were recorded. The system “renders the identification of felons and chronic law breakers . . . an absolute certainty,” claimed Joliet’s records clerk, Sidney Wetmore. “Mistake is impossible.”

But bertillonage had its drawbacks—and its detractors. Carefully measuring feet, ears, and fingers of offenders like Cream was a time-consuming process and skilled, trained technicians were needed to ensure the results were accurate. Tools became worn or bent through constant use, producing results that could match an innocent man to the crimes of someone of similar size and build. And there was no central registry, making it difficult to trace a suspect who refused to reveal where he had lived or worked before his arrest. Some prison officials also questioned the fairness of keeping detailed records of men who had served their time and might never break the law again. McClaughry’s counterargument, that the records were checked only when a former inmate reoffended, highlighted the system’s most serious flaw—finding matching measurements simply proved that a suspect in custody had a criminal record. Unlike fingerprints, which were still years away from being accepted as a forensic tool, Bertillon records could not link an unknown offender to the scene of a crime. “No man can be pursued by the police or by any detective,” McClaughry admitted at a national meeting of wardens in 1890, “by means of this system.”

When Cream emerged from behind the walls of Joliet in the summer of 1891, there was little to connect him with his dark, murderous past. He was a doctor from Canada who had grown up in Quebec City and boasted a medical degree from Montreal’s McGill University. He was also a new kind of killer, choosing victims at random and killing without remorse. A cold-blooded fiend who murdered, the Chicago Daily Tribune would later declare in disbelief, “simply for the sake of murder.” A serial killer, and one of the most brutal and prolific in history. Herman Webster Mudgett, a doctor who went by the name H. H. Holmes, killed at least nine people and would come to be considered one of America’s first serial killers. But by the time Holmes claimed his first victim in 1891 and long before the infamous Jack the Ripper terrorized London in 1888, Cream was suspected of killing as many as six people, most of them deliberately poisoned with tainted medicine. His latest victim had been the husband of his mistress, and this was the murder that had consigned him to a hovel-like cell in Joliet. His earlier victims—two in Canada, including his wife, Flora Brooks, his patient Catharine Gardner in London, Ontario, and three more in Chicago—were young women who were pregnant and desperate to induce an abortion; they had made the tragic mistake of trusting their doctor with their lives.

In an era when police investigations were often cursory and forensic science was in its infancy, detectives lacked the tools and expertise needed to track down such a formidable foe. Few could imagine such monsters existed. But this only partly explains how Cream had gotten away with murder in two countries before he finally had been locked up in Joliet. Cream’s credentials and professional status, bungled investigations, corrupt police and justice officials, failed prosecutions, and missed opportunities allowed him to kill, again and again.

The thin paper trail documenting Cream’s shocking crimes was scattered from small-town Canada to Illinois, with only fading memories, forgotten court files, and yellowing newspaper clippings to connect the dots. The Bertillon identification system, cutting-edge technology for its time, was powerless to prevent a convicted criminal from vanishing like a ghost. If a former inmate wanted to disappear after his release, to hide his past—as Cream most certainly did—all he had to do was change his name.

London, Fall 1891

A man clad in a mackintosh to outsmart the day’s showers, a top hat covering his bald head, turned up at the door of a townhouse at 103 Lambeth Palace Road. His name was Thomas Neill, he told the landlady, and he was in search of lodgings. He took the upper-floor room at the back. It was October 7 and Cream was back in Lambeth, a downtrodden maze of grimy slums and smoky factories across the Thames from the gothic splendor of the Houses of Parliament. It was a London neighborhood he knew well: his rooming house stood opposite St. Thomas’ Hospital, where he had been a medical student more than a decade earlier. He could not help but notice that a new building, just downriver from the tower of Big Ben, had been erected since his last visit. Faced with bands of red brick and white stone and set on a foundation of granite quarried by inmates of Dartmoor and other prisons, it was the new headquarters of Scotland Yard.

Cream was in the heart of the world’s largest city, the capital of an empire at its zenith. Swaths of scarlet on globes and maps staked Britain’s claim to the far-flung colonies and territories—and tens of millions of people—under Queen Victoria’s rule. London was a sprawling metropolis of more than five million, a glittering bastion of wealth and power built on a foundation of poverty, crime, and desperation. Church spires and the giant teapot dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral pointed skyward from a sea of slate roofs and chimneys belching black coal smoke. A chaos of carriages, freight wagons, and horse-drawn omnibuses clogged the main streets. At night, the sidewalks became a sea of bowlers and wide-brimmed, feathered hats as men and women passed like ghosts through a netherworld of flickering gaslight and sinister fog. Pickpockets shouldered their way into the crowds in search of watches and billfolds. Prostitutes scanned the audiences at West End theaters and music halls in search of customers or strolled adjacent the Strand, transforming the busy thoroughfare, one observer lamented, into “one of the scandals of London.” Enclaves of the rich and privileged rubbed shoulders with foul, dangerous slums like Whitechapel where, just three years before, the notorious Jack the Ripper had brutally murdered five women. To an editor at the city’s Daily Chronicle, London was a modern Sodom and Gomorrah, “a great sin-stricken city.”

Lambeth rivaled Whitechapel as one of the city’s poorest, dirtiest and most crime-ridden neighborhoods. Not even the police were safe—one bobby, a rookie on one of his first patrols, confronted a group of Lambeth thugs and was thrown through a plate-glass window. When the journalist Henry Mayhew set out to expose London’s nineteenth-century underworld, he headed for the “well-known rookery of young thieves in London.” Children as young as five, he discovered, roamed the streets in ragged clothing, stealing to survive. “Fagin, Bill Sikes, and Oliver Twist would have all seemed quite at home in Victorian Lambeth,” the celebrated author Simon Winchester has written. “This was Dickensian London writ large.”

Lambeth’s industries choked the air with smoke and soot. Maudslay’s foundry forged parts for the steam engines, pumps and other mechanical marvels that powered the Victorian Age. Earthenware jugs, chimney pots, and drainpipes were fired in Henry Doulton’s famous pottery works. Overhead, trains puffed and clacked on elevated tracks that sliced through the heart of the neighborhood. Their destination was Waterloo Station, one of the city’s major terminals. Thousands of people—commuters who worked in the city, travelers bound for points in southern England, steamship passengers newly arrived from abroad via Southampton—passed through its doors every day. Even the dead disturbed the living. London’s cemeteries were so overcrowded that a special railway, the Necropolis line, shunted corpses from a local station to graveyards south of the city. Lambeth, the London historian Peter Ackroyd would note, “was, in every sense, a dumping ground.”

It was also considered the “most lurid and beastly” of the city’s red-light districts. The neighborhood surrounding Waterloo Station, a magnet for streetwalkers, became known as Whoreterloo. Brickwork supports for the station’s elevated tracks offered secluded spots where business could be transacted—the succession of “dark, damp arches,” one resident complained, “encouraged the more disreputable of the population.”

Prostitutes were described as “unfortunates” in the press, but some of the women working in the brothels, propositioning men on the street, or picking up clients at the Canterbury, Gatti’s, and other Lambeth music halls considered themselves fortunate. Life was precarious for young women from poor, struggling families. A sudden misfortune—the death of a parent or husband, the breakup of a marriage or relationship, losing a low-paying job as a maid or toiling in a factory—could leave them to fend for themselves. Some working-class women turned to prostitution, the British academic Kathryn Hughes noted in an exploration of Victorian life and attitudes, when “the usual ways in which they got an income from their bodies—by working as a milliner, or a domestic or a factory hand—had come up short.” Selling sex, even for a few weeks or months, might be their only option, and it offered something most women, regardless of their social standing, were denied in the Victorian world: income and independence. One Lambeth prostitute told Mayhew she earned as much as four pounds a week, far more than she had made “workin’ and slavin’” as a servant in Birmingham.

Prostitutes seemed to be everywhere in Lambeth. There were “more women in the street than ever, and they are more brazen and persistent,” complained Rev. G. E. Asker of St. Andrew’s Church. Even he was being propositioned as he walked through the neighborhood. “The brothels are many of the perfect hells,” Asker added. “Shrieks and cries, ‘murder’ and so on, frequently are heard.”

For Lambeth’s newest resident, it would be a perfect hunting ground.

* * *

Cream became a regular at Gatti’s Adelaide Gallery Restaurant on the Strand. The restaurant’s decor was elegant—vaulted ceilings, stained glass, ornate plasterwork, a palate of blue and gold—and it was a favorite of the theater crowd. Actors and playwrights from nearby playhouses claimed many of its marble-top tables. One day, when most of the seats were taken, he shared a table with another man.

He introduced himself as Thomas Neill. He was educated, tastefully dressed, and “well informed and travelled, as men go,” the other diner recalled. They shared meals many times, with Cream preferring bread and cheese, washed down with beer or gin, to the plovers’ eggs and other delicacies on the menu. He spoke about how much he enjoyed attending the city’s music halls. He talked about money and seemed obsessed with poisons. But most of time, he talked about women.

“His language about them was far from tolerable or agreeable,” his dining companion had to admit. Cream carried around a collection of pornographic photographs, which he delighted in showing to his new friend and to other diners. He was restless and fidgety and could not stand still, even when drinking at the restaurant’s bar. And he was always chewing something—gum, tobacco, or the end of a cigar, his jaws “moving mechanically like a cow chewing the cud.” He seemed wary of every patron and waiter who approached his table. He rarely smiled, and his laugh sounded forced and fake, as if he were the villain in a melodrama. And people could not help but notice that his left eye turned inward, giving him a crazed, sinister look. Cream later claimed he had come to London to consult an eye specialist, and one of his first stops after his arrival had been the office of a Fleet Street optician. James Aitchison diagnosed his condition as hypermetropia, or farsightedness—his eyes focused improperly, blurring his vision and causing severe headaches. Cream had been suffering from the condition since childhood, Aitchison concluded, and had needed glasses for years. He supplied two pairs of spectacles to correct his vision.

The more his dining companion learned about Cream, the more troubled he became. “He was exceedingly vicious, and seemed to live for nothing but the gratification of his passions,” he remembered. “His tastes and habits were of the most depraved order.” And he made no secret of his drug use. Cream was constantly taking pills, three or four at a time, that he said contained cocaine and morphine as well as strychnine, a deadly poison used, in minute quantities, as a stimulant in medicines. The pills relieved his headaches, he said. They were also, he seemed delighted to add, an aphrodisiac.

Getting narcotics and poisons in London, Cream had discovered, was easy. He called at a chemist’s shop on Parliament Street—just around the corner from Scotland Yard’s new headquarters—and identified himself as a doctor from America, visiting the city to take courses at St. Thomas’ Hospital. The clerk, John Kirkby, could not find the name Thomas Neill in the shop’s register of licensed physicians. “I am not in the habit of selling poisons to persons whose names I cannot find in the register,” he would say later. Access to poisons was restricted by law, and if Cream could not prove he was a doctor, he should have been required to produce someone known to the pharmacist to vouch for him. But Kirkby made an exception and took this new customer at his word. He filled Cream’s orders for opium and strychnine several times that fall. When Cream asked for empty gelatin capsules of a size not in general use in Britain, Kirkby helpfully tracked them down from a supplier. Doctors and druggists filled them with medicine too bitter tasting to be taken on their own.

Cream did not say how he intended to use the strychnine or the hard-to-find capsules. Kirkby did not ask.

___________________________________

Excerpted from The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer, published by Algonquin Books on July 13.

Dean Jobb’s previous true crime book, Empire of Deception (Algonquin Books), was the Chicago Writers Association’s book of the year. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia.