I was delighted when Otto Penzler asked me to be involved in this new short story project. I felt the request implied he thought I had something worthwhile to offer on the subject. I’m always delighted to create that impression. But sadly, on this occasion, an impression is all it is. I don’t know much about short stories, or their true origins, mechanisms, or appeal. My only consolation is I’m not sure anyone else does either.

What is a short story? Clearly there’s a clue in the name. A short story is a story that’s short. A story is an account of events – in this context almost certainly made up – and the adjective short acts to separate the form from other types of accounts that customarily tend to be longer. As a compound noun, short story first appeared in print in the year 1877, alongside other compound nouns new that year, including belly button, coffee table, cold storage, genital herpes, medical examiner, musical chairs, stock option and toilet paper.

Some of those things were genuinely new in the 1870s – cold storage, certainly, which shook up food supply and started the decline of landed aristocracies by breaking their local monopolies on agricultural production. And coffee table was new as well, I suppose, given the rise of the Victorian middle class, and stock option, and toilet paper, possibly. But others among those things were merely newly named – for example belly button, which of course we’ve all had forever, and probably genital herpes, too.

Which category did short story fall into – new, or just newly named? The latter applies, as a matter of record. A by-then-established literary form was first called a short story in the year 1877. So, newly named. But, without doubt, wrongly named. And far from being new, the form could be the oldest we have ever known.

No one knows when fiction was invented. Or, long before that, the syntactical language that permitted it. Spoken words leave no archeological trace. As soon as their last echoes die away, they are gone forever. All that is left is speculation. Scientific advances in the field of human origins have been spectacular, but scientists don’t like to speculate. Just the facts, ma’am.

They will agree, however, on a couple of things. Some explanation is needed, of how a relatively weak and vulnerable and not-very-successful hominid proto-human later came to dominate the whole world and reach outward into the universe. How did that happen?

And scientists will agree that complex, coherent, if-this-then-that language, with a plan B, and a plan C, would have required a big brain. Which they’re happy to show us, because that’s back in the realm of facts. It’s right there in the ground: our brains got big enough less than half a million years ago. There’s a vigorous, but very polite, argument whether language colonized a freak mutation, or whether the increase in size was itself driven by the absolute need for language. But either way, that’s when it all started.

And it was crucial. A single human was slow and weak. Prey, not a predator. But a coordinated group of a hundred humans was the most powerful animal the earth had ever seen. Tooled up, organized, drilled, rehearsed, if this, then that, plan B, plan C. Language came to the rescue. It made all the difference. We survived. Not that things were easy. Pressures were many and various, and sometimes catastrophic. But we stood a better chance than most. We had lengthy discussions, accurate assessments, correct recall of past events, realistic projections into the future.

In other words, non-fiction saved the day. Language was a lifesaver because it was entirely about truth and reality. It could have no value otherwise. Possibly it stayed that way for hundreds of thousands of years. Then something very strange happened. We started talking about things that hadn’t happened to people that didn’t exist. We invented fiction.

When exactly? It’s impossible to say. The echoes have died away. But we can speculate. Just the guesses, ma’am. We know – because it’s right there in the ground, or on rocky walls – that music and representative art date back almost 70,000 years. Both involved some kind of technical intervention – drums, with stretched skins, hollow bone flutes, with holes carefully drilled for finger stops, pigments found and mixed, twigs chosen and frayed for application – whereas storytelling required no technology. We already had what we needed. We had expressive voices, and sophisticated language. So, it’s reasonable to guess storytelling happened much earlier than art or music.

Why did it happen? Not to fill our leisure time. We had none. We were still deep in prehistory, still cognitively pre-modern, still evolving. Everything we did had a singular purpose: to make it more likely we would be alive tomorrow. Any notion or activity that didn’t meet that need quickly died out, literally. How do we square that circle? How did stories make it more likely we would be alive tomorrow?

By encouragement, and empowerment, and subtle instruction, surely. Perhaps the first made-up story was about a boy who came face to face with a snarling saber-tooth tiger. Maybe the boy turned and ran as fast as he could and made it safely back to the cave. Which was encouragement, in the strategic sense of maintaining morale, by delivering the message that not everything has to turn out bad. And, also in the tactical sense, in that the specific terrain outside the cave was survivable. Which was the subtle instruction. You had to go out and hunt and gather. A balance had to be struck between reactive caution and proactive boldness, such that the tribe endured.

Then maybe a thousand years later the story evolved to where the boy swings his stone ax and kills the saber-tooth tiger. The first thriller, right there. The boldness is turned up a notch. The tribe not only endures, but prospers.

It’s worth noting in passing those who neither prospered nor even ultimately endured – our very distant evolutionary cousins, the Neanderthals. On its face, that’s a surprise. Compared to us, Neanderthals were faster, stronger, healthier, better toolmakers, better organized socially, and more solicitous of one another. They had bigger brains than us, which surely means they had sophisticated language, possibly even better than ours. Yet they went extinct, almost 40,000 years ago – granted, after hundreds of generations of extraordinary stress from the Ice Age climate emergency. But we survived it. Why us, and not them?

Those given to fanciful speculation might construct a clue from the actual in-the-ground evidence. Neanderthal settlements tell of occupation by sober, sensible people. They were sporadically nomadic, like all hunter gatherers, but almost invariably their next settlement was barely out of sight of their last. There is no evidence they ever crossed a body of water without first being able to see land on the other side. The overall impression is one of stolid caution.

Whereas we – homo sapiens – were nuts in comparison. We were bold to the point – beyond the point – of recklessness. We ranged thousands of miles into unknown regions. Hundreds of times we launched bark hulls onto giant oceans, and only a tiny percentage can have survived to see the far shore. If any. Our brains were wired differently. The Neanderthals did things we didn’t, and we did things they didn’t.

Did that include making things up? Nothing about the jump from non-fiction to fiction was biologically preordained or inevitable. It just happened to us. Maybe it just didn’t happen to our distant cousins. Maybe their sober, sensible, stolid brains couldn’t provide the necessary pathway. Maybe wild imagination was required to fire the spark.

What if Neanderthals never left the world of non-fiction? Never entered the land of make-believe? And thereafter, despite their speed and strength and health, and their technical and social skills, what if they didn’t make it because of that? Because they didn’t have story, to encourage and empower and instruct. Maybe that tiny margin made all the difference.

What do we know about the stories we had and they might not? Nothing, of course, but we can speculate. There would have been a strong central strand, be it encouraging, emboldening, instructing, warning, scaring, or whatever else, all wrapped up in context and diversion, and verisimilitude, but not quite. There would have been a rim of unreality, however faint, to expand our experience, which was the evolutionary purpose of story, to take us places we wouldn’t normally go, to shine a beam into corners normally left dark. The stories would have been concise, pithy, and focused. They wouldn’t have taken long to tell. Survival was a full-time job. Bandwidth was precious.

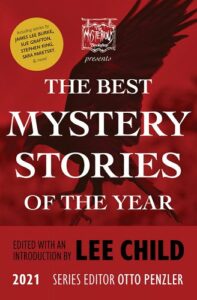

And now, a hundred thousand years later, you find yourself currently holding in your hands an anthology featuring twenty outstanding contributions from twenty outstanding authors. I know many of them personally. I bet they think this foreword is crazy. I bet they don’t agree with a word of it. I bet they all have more plausible explanations. I bet they’re going to quote from my first paragraph, right back at me: I don’t know much about short stories, or their true origins, mechanisms, or appeal.

But equally, I bet you’ll agree their stories fit pretty neatly inside the hundred-thousand-year-old scaffolding described two paragraphs ago. Therefore, you’ll also agree the items included here should be called simply stories, and those other things their authors produce from time to time should be called long stories. Seniority should count for something, after all. Naming rights, at least.

Lee Child

Wyoming

January 2021

***