Merriam Modell was at a career crossroads. It was 1960, and she had spent the past decade publishing increasingly successful suspense novels, largely centered around the terror lurking in ordinary domestic situations. Her most recent thriller, Bunny Lake Is Missing, with its premise of a child vanishing from her first day at school and a mother written off as hysterical, had struck a chord with the American public grappling with similar anxieties upon its 1957 release.

But Modell had reason for ambivalence, as she conveyed in an interview that year with the Yonkers Herald-Statesman. For Modell’s success was not under her own name: she had adopted the pseudonym of Evelyn Piper beginning with The Innocent (1949), the switch in genre and name prompted by disappointing sales of two earlier, non-crime novels. Those books, The Sound of Years (1946) and My Sister, My Bride (1948) were more about character-driven conflicts than plot twists. And even though she clearly excelled at plot, based on the public response to her work as Piper, Modell was unsure if she wanted to continue with a winning formula.

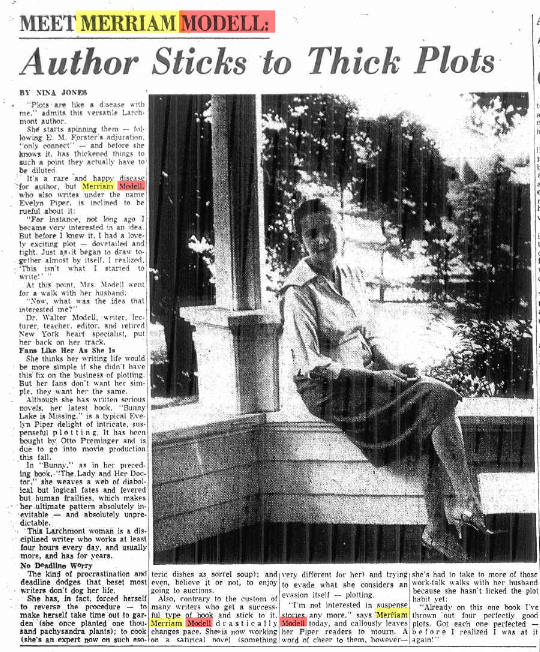

“Plots are like a disease with me,” she told the Herald-Statesman‘s Nina Jones, who had visited Modell at her home in Larchmont, a Westchester suburb about 40 minutes north of New York City. “For instance, not long ago I became very interested in an idea. But before I knew it, I had a lovely exciting plot—dovetailed and tight. Just as it began to draw together almost by itself, I realized, ‘This isn’t what I started to write.'”

She was hoping to write a more satirical novel, one that wasn’t quite like the Pipers, but wasn’t like her earlier work, either. “Already on this one book I’ve thrown out four perfectly good plots. Got each one perfected—before I realized I was at it again!”

Modell would stay “at it again” after all. Mere months after the interview, Hanno’s Doll (1961) extended the Piper suspense streak, as did The Naked Murderer the following year. And The Nanny (1964) reached a comparable success pinnacle to Bunny Lake—including adaptation into a film featuring Bette Davis. After 1970, she published nothing more—not as Evelyn Piper, not as Merriam Modell. I wondered why. I suspected that below the thrill-based veneer of her work was a woman struggling to define herself as an artist when commercial lucre beckoned.

Excavating Merriam Modell turned out to be as complicated an affair as one of her Evelyn Piper plots.

***

Before she was Evelyn Piper, before she was even Merriam Modell, she was Miriam Levant. (According to her son, John, she pronounced it “Le-VAHNT,” unlike the entertainer, Oscar Levant, whom she disdained as “too much of a showoff.”) Her parents, Harry and Flora, had arrived from Russia in 1892 and 1893, respectively, settling, as so many Jewish immigrants did at the tail end of the 19th century, in the hustle and flow of the ever-crowded Lower East Side. By the time Miriam was born in May 1908, the Levants had moved to a tenement on Henry Street, where two more daughters—Virginia and Jean—would be born, a four or five-year age difference between each of the sisters.

It’s not clear when Miriam altered the spelling of her first name. The 1920 census lists her as “Merriam,” but such documents cannot chronicle whether the choice was hers, or an error by the census-taker. Five years later, the New York State census records her as “Miriam,” and she would use the original spelling while studying at Cornell University, and when boarding a ship bound for Hamburg, Germany, in December 1931.

She crossed the Atlantic at a pivotal moment in her life, leaving behind an unsuitable relationship with a man named Jess—about whom she wrote often, later in life, in her journals—with the prospect of a relationship with a more suitable man named Walter on the horizon. Miriam turned heads in New York and in Ithaca, and spent time working as a model, then as an assistant with Borrah Minevitch’s Harmonica Rascals, apparently the oldest and longest-running all-harmonica group. She likely sought similar adventure in Germany, but her arrival there coincided with the rise of Hitler.

Miriam, already keenly aware of anti-Semitism, may have found Germany inhospitable. Or she may have run out of funds after a year or so abroad. Whatever the case, she was back in New York by the end of 1933, and married to the more suitable man. She and Walter Modell were distant relatives who knew of each other growing up, but did not connect in earnest until their college years. Walter would become a professor of pharmacology and author a number of important papers. Miriam, before and after the birth of their son in 1941, threw herself in a different creative pursuit: pursuing a literary career. In doing so, the altered spelling of her first name stuck for good, joining with her married last name in alliterative fashion.

Merriam Modell began by publishing short stories, many of which appeared in the New Yorker beginning in 1937. They tended towards slices of life, of internal conflicts between spouses, parents, children, and the like. Her two novels built domestic drama around grand epiphanies: in The Sound of Years, the wife and mother who so successfully buried a secret pregnancy that the arrival of this long-lost daughter threatens to explode her current life, while in My Sister, My Bride, a woman struggles with what was then thought of as frigidity (now we would classify it a medical condition, like vaginisimus.) Both novels garnered positive reviews but sales were poor—or at least, not strong enough to keep her career going under the Modell name.

Thus, the turn to suspense, and the pseudonym swap. Evelyn Piper garnered rapturous praise from Anthony Boucher’s “Criminals at Large” column in the New York Times Book Review, and Piper’s first book, The Innocent, was nominated for a Best First Novel Edgar Award. The Motive (1950) and The Plot (1951) followed swiftly thereafter, and it seemed as if she would stay on the book-a-year pace followed by so many crime writers.

But Modell, good as she may have been at plotting, was restless. She had moved into suspense waters for commercial reasons, and she felt the shame and defeat of leaving literature behind for genre, warranted or not. She counted the poet Phyllis McGinley and the playwright Jean Kerr as friends, but may have felt competitive with them. Clinical depression, from which Modell suffered throughout much of her life, may have been a factor, too. She wrote several drafts of a critical study of William James and how his works helped lift her out of her depression, but it never congealed into a salable work.

As John, her son, told me in a telephone interview, “To judge from the journals, her writings, even from the novel period, and the suspense story period, were to earn money. It was a repeated theme. It really mattered to my mother, in conversations with editors that she set down: ‘can I do this, will they accept it, will it sell?’”

The Piper suspense novels sold. The other works did not. A several-year hiatus in the 1950s, which included a three-month research trip to London, ended with the publication of The Lady and Her Doctor in 1956. Like the earlier Pipers, its strength is in the characters and in the pacing, as well as a nervy anxiety that burrows under the skin and stays there until the last possible moment. But it wasn’t until Bunny Lake was published the following year that Modell melded her two literary selves into a tangible whole.

***

I reread Bunny Lake Is Missing for the third time in preparation to write this piece. And as with the prior two times, I marveled at Piper’s ability to instill terror, to make the reader identify completely with Blanche Lake’s horror that her 3-year-old daughter is nowhere to be found—not at school, where she should have attended on her first day, not at home, not out and about the streets of Manhattan. “The room was empty” strikes at the nerve center of fright, and Piper only escalates matters from there, when she makes clear that Blanche will not only be blamed for Bunny’s disappearance, she won’t even be believed that Bunny existed at all.

“Call themselves mothers and don’t care enough to take care of their own…Some people don’t deserve to have kids!” one of the nearby neighbors says out loud what so many were thinking. This was a classic 1950s attitude, but it is also a classic contemporary attitude, too. The raw power of this expressed emotion, as with the rawness of Blanche’s anguish the longer Bunny’s vanishing persists, is why Bunny Lake still endures. It’s irony, perhaps, that the novel works less on a plotting level—the ending twist features an offstage villain whose motivations are rooted more in Freudian transference—than on a human behavior level, because Piper spent so much effort coming up with “perfectly good plots.”

But keen observation, no matter the container, will always prevail, as Piper’s comrades in domestic suspense, arms like Margaret Millar, Charlotte Armstrong, and Dorothy Salisbury Davis—all of whom ventured outside of crime fiction to write more mainstream fare at some point in their careers—well knew. Each of these women digressed outside of genre when compelled, and battled their own internal conflicts about whether crime fiction counted as literature. Like Modell, none ever reached the same success level as when working within the suspense realm.

None of these women felt that defining themselves as crime writers was an inferior move. Modell, however, felt otherwise.

***

After The Nanny, Merriam Modell published one more Evelyn Piper book. The Stand-In (1970), frankly, isn’t as good as the earlier books. It meanders, it misses its pacing marks, the fear factor is diminished. She would try again with another suspense novel, but publishers rejected it, and she realized she’d reached the end of the line with genre fiction. “Tastes have changed,” was the conclusion she reached when her agents failed to sell her newest work.

Modell continued to write, but not publish. She tried again with the William James critical study, but again it went nowhere. Eventually she and Walter, suffering from dementia, moved to Pittsburgh to be closer to John, who had moved there to teach history at Carnegie Mellon (where he’s now an emeritus professor.) The move, as John told me, was awful for his mother. She couldn’t drive, so relied on Walter or Larchmont friends to take her places. With her husband’s health failing, she was stranded, but Modell also couldn’t bear to see her husband fail further in assisted living, visiting him a grand total of once before his death in 1991.

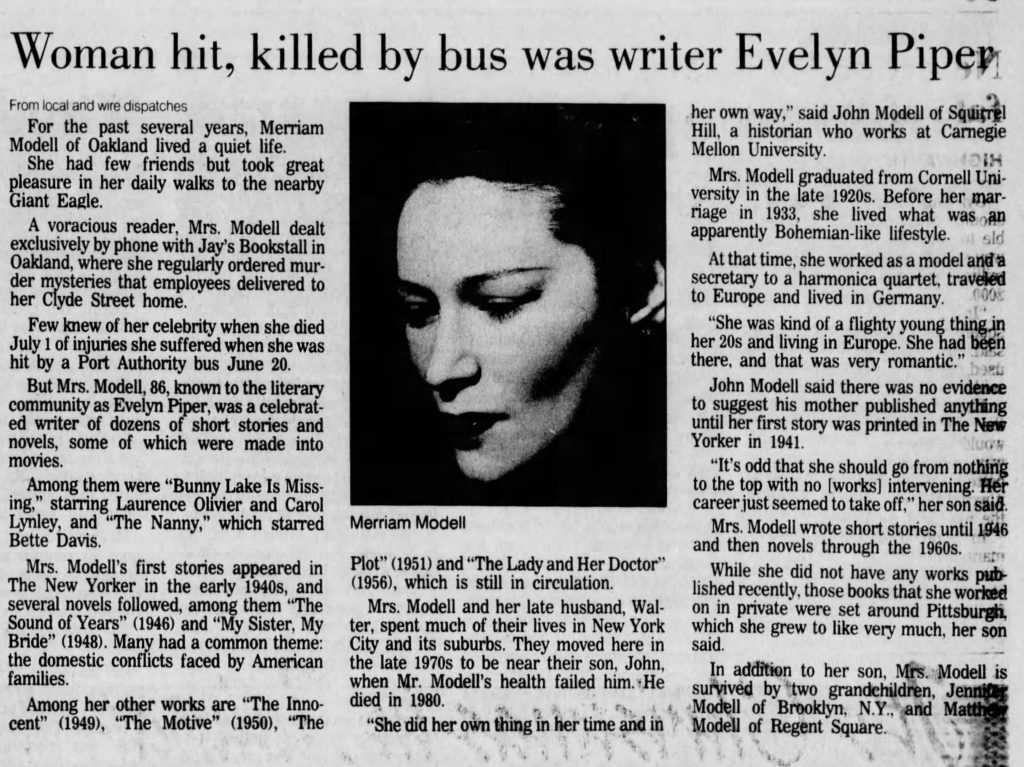

Three years later, at the age of 86, Merriam Modell also passed away. After Walter’s death she had developed a daily routine, leaving her house—situated just a few blocks away from John—to walk the half-mile or so to the nearby Giant Eagle supermarket or to the local library. Modell had stopped writing but she had not stopped reading—she also special-ordered crime novels by phone from Jay’s Bookstall in nearby Oakland.

At some point on the morning of June 20, 1994, Modell started to cross Fifth Avenue. John didn’t know if his mother had visited the library that December morning or if she was still on the way there when a Port Authority bus hit her. Modell was rushed to the hospital and lay comatose in the intensive care unit. She lived a few more days, where became clear her kidneys had been irreparably damaged, and would have to go on dialysis. “In a certain sense, this was no life for her,” said John. “She wasn’t conscious, but perhaps occasionally aware of my presence.” Merriam Modell died on July 1, 1994.

In a lengthy obituary published by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, John noted: “She did her own thing in her time and in her own way.” That’s about as apt a description of Merriam Modell—her life and her work—as I could come up with. She understood domestic terror, from the vanished child to the gaslit mother, the psychotic child to the merciless nanny, the affronted husband on the precipice of murder, because she understood human nature. It defied constraints, it broke loose from narrative form.

Modell self-internalized a battle between literature and genre that did not need to be waged. But by waging it, her suspense novels, as Evelyn Piper, stand out all the more.

***

Featured image credit John Modell