From essays to interviews, excerpts and reading lists, we publish around 80 features a month. And though we’re proud of each day’s offerings, we do have our personal favorites. Below are some of our favorite pieces of writing from the month at CrimeReads.

“Miami Vice: How an Icon of 80s Cool Transformed a City and the Landscape of Television”

by Craig Pittman

“There’s a legend that Miami Vice started with a two-word concept written on a napkin by NBC programming wunderkind Brandon Tartikoff: ‘MTV cops.’ The truth, as usual, is more complicated.” Craig Pittman, expert on all things Florida, charts here the rise of Michael Mann’s iconic cop drama, Miami Vice, a show that came to define so much about the 1980s, but also inspired a fantasy about the city of Miami that eventually, more or less, came true. Pittman skillfully separates the myths from the reality here and shows how a city transformed itself. (Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads managing editor)

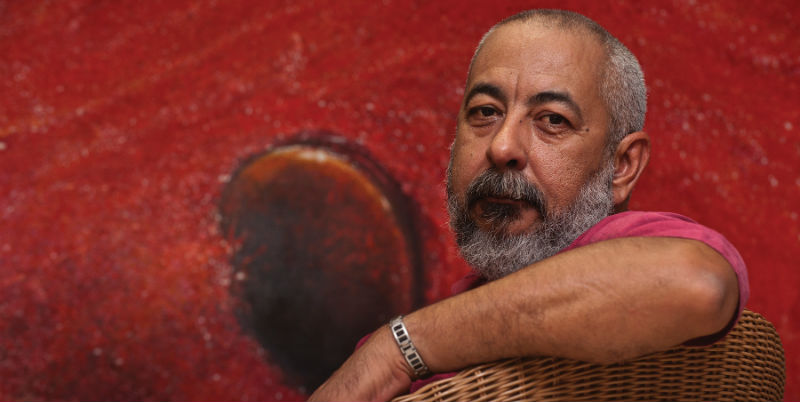

“Havana to Miami: Crime Fiction Across the Straits of Florida”

by Alex Segura

This is easily one of my favorite interviews we’ve run on CrimeReads, partly because I love the work of both authors in discussion, Leonardo Padura and Alex Segura, and partly because in getting together for a conversation they’re also hashing out one of the great, complicated cultural divides in the Americas, between Cuba and Miami Cuba. Segura writes that he went into this interview expecting to find sharp points of conflict, political and otherwise, and came away finding a friend, as well as a fellow artist working through the same kinds of concerns and influences. Padura’s big subject is history, its points of repetition and overlap, and its blind spots. So it seems fitting to me that his conversation with Padura should serve as a kind of bridge across history. (DM)

“The Evolution of Walt Longmire: Somewhere Between Laughter and Death”

by Scott Montgomery

The Longmire series, a modern western epic with a devoted following, is one of the most interesting crime series around, and in the decades Craig Johnson has been creating these tales, the evolution of his main characters has been fascinating to follow. Here, bookseller and Longmire guru Scott Montgomery breaks down the long-running series into its different phases and explains how the characters—and their world—have changed and how it has persisted. For anyone who loves the Longmire series, this article is a lively engagement with the books; and for those looking for a point of entry into the world of Longmire, Montgomery is the perfect guide. (DM)

“Edna Buchanan’s Miami”

by Sarah Weinman

Weinman here teases out a long, complicated history with the works of Edna Buchanan, the trailblazing crime writer who worked the Miami crime beats for decades before turning to fiction. Buchanan was from New Jersey, but came to be as closely identified with her adopted city, Miami, as almost any writer around. Her knowledge of Southern Florida’s criminal underbelly was vast, as was her imagination, and the legacy she leaves behind is fascinating for a close study, which Weinman provides in this incisive, engaged reading of an author’s work and life. (DM)

“What Fiction Teaches Us About the Allure of Cults”

by Kali Wallace

While most prefer to think of those who join cults as, well, pathetic, that ignores the basic fact that most people don’t join cults – they join communities that become cults. Kali Wallace, author of new science fiction thriller that explores the nature of community and belief in the distant future, has elegantly distilled the allure of cults to its practical essence in this essay, and shows us that, while we might choose to believe ourselves entirely different from the vulnerable souls who fall under the sway of the magnetic leader, the truth is much more prosaic. (Molly Odintz, CrimeReads associate editor)

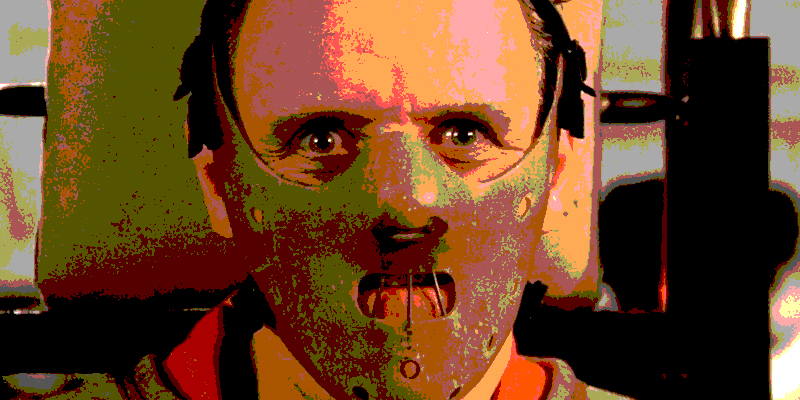

“Hannibal Lecter: 20 Years Later”

by Patrick Sauer

Patrick Sauer’s riotous foray into the history of Thomas Harris’ most grand guignol novel, Hannibal, is, dare I say it, just as entertaining as the series itself! Torn between admiring the novel’s good notes, and pillorying its more over-the-top moments, Patrick Sauer primarily imbues this article with a bemused affection for a very strange book whose titular character has had an outsized (and somewhat inexplicable) impact on popular culture to this day. When you finish reading this essay, you will think, “Is Thomas Harris…fucking with us?” And you will not know the answer to that question, yet you will love Hannibal Lecter all the more for asking it. (MO)

“Domestic Horror: A Primer”

by T. Marie Vandelly

Move over, domestic suspense—it’s time for domestic horror to take center stage! Or perhaps to hang out in the wings, making scary noises… Here, debut novelist T. Marie Vandelly takes us through her favorite tales of domestic horror (a redundant phrase, for someone who hates cleaning as much as I do), from Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw to Attica Locke’s The Cutting Season, and shows us a literary world where home does not mean comfort, so much as isolation, hauntings, and a slow descent into madness. (MO)

“Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Noir”

by Zach Vasquez

A place that manufactures as much happiness as Hollywood is bound to be a miserable place on the inside, and of course a town known for cinema would use films as the language of disenchantment. Here, Zach Vasquez rounds up the best classic noirs set in Hollywood, not including L.A. Confidential, because a) that’s on every other list, and b) it was made in the 90s and nothing counts as a classic unless it’s at least 30 years old (which means I turn into a classic on my next birthday). This is the perfect list for anyone waiting for theaters to get slightly less crowded before going to see the new Tarantino movie! (MO)

“My 35-Year Love Affair with Marjorie Morningstar”

by Laura Lippman

In this deeply felt, deeply lived essay, Laura Lippman reckons with her thirty-five year love affair with Herman Wouk’s Marjorie Morningstar, a 1955 novel about a young Jewish woman making her way in New York. Lippman interrogates her own evolving relationship with the book and asks the pivotal question, “Is MM a great book?” The tentative answer: “I don’t know, I’m too close to it. But it is a serious book that finds a big, sprawling story in what seems like a small, narrow life.” Lippman’s reading is sure to touch a nerve for any dedicated, passionate reader out there. (DM)

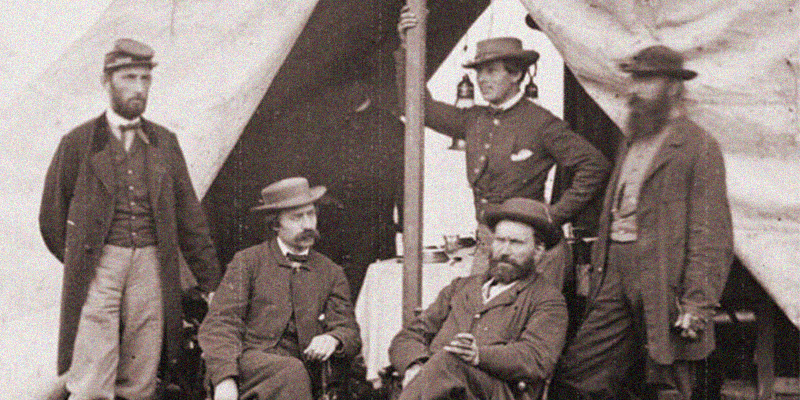

“Pinkerton Spy, Feminist Icon”

by Nile Cappello

There is nothing better in this cruel world than discovering the existence of a real-life nineteenth-century lady detective. Nothing. In this historical overview, Nile Cappello presents Kare Warne, America’s first female (private) investigator, who at age 23, showed up to the Pinkerton Detective headquarters and talked herself into an unprecedented hiring. She was so good at her job that she inspired the creation of Pinkerton’s Female Detective Bureau, rose through the ranks of the company, and became an investigator on the plot to assassinate Lincoln. It’s a great, girl-power narrative, but it’s also an essential historical account; as women’s labor continues to be underpaid and undervalued en masse around the world, and as tremendous female accomplishments continue to go undercompensated (looking at you, USWNT), circulating the biographies of women who refused to be excluded from male-dominated professional realms is a crucial act of both solidarity and resistance. (Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads editorial fellow)

“The Tragic, Violent History of the Brooklyn Waterfront”

by Nathan Ward

The Great Depression-era Brooklyn waterfront is a mythic landscape of bygone New York City–the inspiration for an entire genre of literature and, most famously, the symbolic setting for Elia Kazan’s monumental film On the Waterfront. In his article, Nathan Ward makes an effective sweep of this setting’s pop-culture impact, but concentrates on historical particulars. Ward’s piece emphasizes the struggle between big and small—how a single life can inspire a canon, how individual dockworkers are defeatable but unions are mighty, how an outspoken man can easily be quelled by the vast and corrupt mob engine controlling the shores. With this scale in mind, Ward tells of the murder of real-life longshoreman and activist Peter Panto and his paradoxically heroic death (dying symbolically for everything and literally for nothing). Ward is determined not to let the real-life Panto’s life be forgotten, or his story be backgrounded to the legacy of the genre his sacrifice inspired. (OR)