Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure.

At the time, Christie was married to an officer in Britain’s Royal Flying Corps and working at a hospital in Torquay, England, first as a nurse and subsequently in the dispensary, preparing and providing medicines. It was in the latter job that she developed a fascination with poisons that would endure over the next six decades, supplying murderous means in many of her best-known books, including that very first one, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, which was published 100 years ago this month.

Styles was an early and influential contribution to what’s now called the Golden Age of detective fiction, a period that stretched arguably from the 1920s through the 1940s. The book tosses us into the company of Captain Arthur Hastings, a soldier who’s been invalided home from World War I’s Western Front and has accepted an invitation to spend part of his sick leave at Styles Court, the Essex country estate of his boyhood acquaintance John Cavendish. However, his peace there is soon upset by the slaying of Cavendish’s elderly, widowed, and wealthy stepmother, Emily Inglethorp—an incident that awakened the household near the close of a summer night. Afterward, Hastings seeks help with the investigation from Hercule Poirot, a retired but once illustrious Belgian police detective Hastings had met before the war, and who has recently been living as a refugee in a cottage near Styles.

In short order, Poirot confirms his suspicions that the deceased was done in by strychnine, “one of the most deadly poisons known to mankind,” though precisely how she was dosed with that bitter neurotoxin is unknown. As is the identity of her killer. The suspects, however, are plentiful, among them John Cavendish and his younger brother, Lawrence, whose claim on their stepmother’s fortune is in doubt; Emily’s most recent and significantly more junior husband, Alfred Inglethorp, described as “a rotten little bounder”; Evelyn Howard, the late grandame’s hired companion, who exhibits singular animus toward Alfred; Mary Cavendish, whose love for husband John has suffered severely amid his dalliances and her own drab flirtations; and Cynthia Murdoch, Emily’s protégée, who happens to work in a dispensary. It’s up to Poirot, with aid from Hastings and Scotland Yard Inspector James Japp, to weigh motives and opportunities and finally suss out who among the Styles Court habitués was responsible for Mrs. Inglethorp’s premature dispatching.

Although Christie’s prose here is quite economical, her efforts at misdirection are masterful and her plotting elaborate. The idea of using strychnine as a weapon came, of course, from the author’s hospital experiences. It “could not have come to her otherwise,” explains Laura Thompson in her 2018 biography, Agatha Christie: A Mysterious Life, “as it depends upon a knowledge of poisons. In fact it is impossible to reach the solution to Styles without this knowledge: the reader may guess right as to the culprit, but the guess cannot be proved without knowledge of the properties of strychnine and bromide. So Agatha’s first detective novel was, in a sense, her only ‘cheat.’”

Over the last century, myriad editions of The Mysterious Affair at Styles—the first of Christie’s 33 Poirot novels—have reached print, some of them quite handsome, while others make you wonder what their designers were thinking. To commemorate this month’s anniversary, I’ve gathered examples from all points on that spectrum.

___________________________________

ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITIONS

___________________________________

John Lane (U.S.), 1920: As the story goes, The Mysterious Affair at Styles was rejected by as many as half a dozen publishers in Great Britain. By 1919, Christie had all but lost hope of ever seeing her novel in print. So she was astonished to suddenly receive a missive from John Lane, the co-founder (with Charles Elkin Mathews) of a London-based publishing house called The Bodley Head, asking that she meet to discuss the future of her manuscript. “John Lane did a clever job on Agatha, recognizing both a talent and an easy touch when he saw one,” writes Laura Thompson. “By making her feel grateful—and emphasizing the need for alterations—he tied her into a contract for five more books with The Bodley Head, at a royalty rate only slightly above the one being offered for Styles, which was 10 per cent on any English sale of more than 2,000 copies. She barely noticed this clause, as she had absolutely no thought of writing five more books.” After Christie made the requisite (among them, relocating her yarn’s climactic chapter—in which Poirot explains who- and howdunit—from a courtroom to the salon at Styles Court), Styles was serialized in 18 parts in The (London) Times Weekly Edition, beginning on February 27, 1920. In book form, it debuted under the John Lane imprint in the United States in October of that same year; the first UK release, from The Bodley Head, came in January 1921. Both hardback editions carried the dust jacket above, painted by American artist Alfred James Dewey (1874–1958) and showing what are likely members of the Styles household crowding the hallway outside Emily Inglethorp’s bedroom, candles in hand, drawn by the sounds of her “tetanic convulsions.” Beneath that wrapper was a brown cloth cover boasting an Art Deco design.

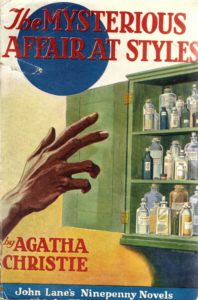

John Lane’s Ninepenny Novels (UK), 1932: Selling Christie’s fiction between hard covers lent it “an air of highbrow respectability,” notes Jessica Davies Porter in The Journal of Publishing Culture. Yet not everyone could afford such handsome goods. So Lane and The Bodley Head tried reprinting The Mysterious Affair at Styles as part of their “Ninepenny Novels” series, a cheaply bound array of paperbacks that also included now largely forgotten tales on the order of William J. Locke’s The Beloved Vagabond (1906) and Ben Travers’ Rookery Nook (1923). That series proved “unsuccessful,” says Porter, “‘a total failure in no time at all.’” The front of this edition of Styles, though, has its attractions. The art is attributed to Vernon Soper (1899–1945), a fairly obscure but still skilled London illustrator who worked primarily for children’s book publishers. His portrayal of an unidentified hand reaching sinisterly toward a medicine cupboard was plainly inspired by strychnine’s role in this novel.

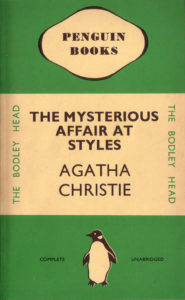

Penguin (UK), 1935: This cover may look unremarkable, but it signaled a major endorsement of Christie’s literary endeavors. In 1935, Allen Lane, the nephew of Bodley Head’s co-founder (who’d died a decade earlier), was serving as that company’s managing editor. He was convinced that a market existed for inexpensive, quality books that could be peddled at corner newsstands and hectic railroad depots, and that those paperback reprint sales would not destroy all customer demand for hardcover editions. So he launched—together with his brothers Richard and John—the now-famous Penguin imprint. Its first 10 paperback releases, all uniformly designed with three thick bands of color on their fronts and their titles in the Gill Sans-Serif Bold font, went on sale in 1935. The Mysterious Affair at Styles was number six in that line, carrying green bands to mark it out as crime fiction (as opposed to orange for general fiction, dark blue for biographies, etc.). The only other mystery among those initial 10 was Dorothy L. Sayers’ The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928). By 1936, Penguin had become a separate enterprise and was on its way to peddling millions of affordable works annually.

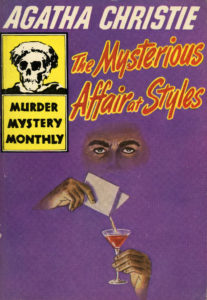

Avon Murder Mystery Monthly (U.S.), 1944: References to poisons and their villainous administration quickly became a Styles cover cliché. For instance, this edition—part of a now highly collectible succession of 1940s softcovers—provides the barest rudiments of a killer’s visage, as he (or could it be she?) pours a fatal dose of what we can only presume is strychnine powder. This artwork is of course flawed: at no point in Christie’s story is it suggested that Emily Inglethorp succumbed after supping from a piece of stemware. Nevertheless, it’s a haunting cover, the picture attributed to one “A. Gonzales,” whose talents showed up as well on other 1940s Avon fronts.

Avon (U.S.), 1951: Paperbacks of the 1950s and ’60s—catering often to male audiences—were notorious for their lurid, highly sexualized cover illustrations, some of which only vaguely represented the stories within. The scene portrayed here by artist Barye Phillips (1924–1969) comes from Chapter 3, in which John Cavendish and Hastings, fearing for Emily Inglethorp’s life, break down a locked connecting door to her bed chamber, only to witness “her whole form agitated by violent convulsions.” Both men had been stirred abruptly from their slumber, and had thrown on “dressing gowns” (robes). So who’s the gent shown still sporting a dinner suit and bowtie in the early morning hours? The blonde he’s supporting in the doorway at least looks as if she might’ve just abandoned her bed sheets, but she too is an enigma. The story mentions several women in attendance when the unfortunate Mrs. Inglethorp is discovered, but Christie failed to report that any of them was a bombshell who’d rushed to the scene naked, save for an unbelted turquoise housecoat—and you would think such facts deserved raising. Phillips obviously labored under the belief that an eye-catching image was more sellable than a slavishly accurate one…and he wasn’t wrong. The back cover features a drawing of the floor at Styles Court where Emily met her end, which—while less elaborate than the Dell “mapback” paintings of the early to mid-1900s—was certainly serviceable.

Pan (UK), 1955: At last we’re given a full-color depiction of this tale’s punctilious sleuth, Hercule Poirot. Christie describes him in Styles as “an extraordinary looking little man. He was hardly more than five feet four inches, but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military. The neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound. Yet this quaint dandified little man who, I was sorry to see, now limped badly, had been in his time one of the most celebrated members of the Belgian police. As a detective, his flair had been extraordinary, and he had achieved triumphs by unravelling some of the most baffling cases of the day.” The portrait above—rendered by British artist Roger Hall (1914–2006)—imagines Poirot concentrating over a coffee cup, one of which was found curiously “smashed to powder” at Emily Inglethorp’s bedside.

Avon (U.S.), 1957: While it’s easy to recognize on this front the figure of Poirot, leaning on the right with his black suit and hat, patent leather shoes, and walking stick, the winsome young woman in the foreground defies identification. It’s not Emily Inglethorp, described by Christie as “not … a day less than seventy now,” “a handsome white-haired old lady.” Scratch, too, Evelyn Howard, “a pleasant-looking woman of about forty, with a deep voice, almost manly in its stentorian tones, and … a large sensible square body, with feet to match.” Maybe it’s meant to be Cynthia Murdoch, pictured as having “great loose waves of … auburn hair.” Then again, the illustrator may have had no particular model in mind, but have worked merely from the dubious belief that poison—especially when it comes in perfume-style bottles, I guess—is a more popular murder weapon for women than men. The artist is something of a mystery, too. “David Stone,” as he signed his painting, is probably the same person who created this 1958 front, also for Avon, and who later became better known as David K. Stone (1922–2011).

Great Pan (UK), 1959: C’est un miracle! Between the 1955 Pan cover and this one, Christie’s detective appears to have recovered some of the tresses previously stolen from his egg-configured noggin by age. Poirot was less fastidious about his coiffure than he was about his mustache, which he waxed, scented, and curled almost to the point of caricature. However, his hair did remain suspiciously black, even in his advancing years; Poirot denied dyeing it, but admitted that he applied to it a special “tonic” called Revivit. The art here is credited to Jack Keay (1907–1999), a British painter who produced additional Christie covers, as well as the fronts for works by John Creasey, Victor Canning, and Ross Macdonald.

Pan (UK), 1969: This photographic front is rather like my cooking: the correct ingredients may all be there—in this instance, a bunch of keys, fragments of a china cup, a stain on the rug, all clues that Poirot encounters in Chapter 4—but the spice of imagination is signally deficient.

Bantam (U.S.), 1978: Sometimes the simplest design is the best. Brought to market just two years after Christie died from natural causes at age 85, this paperback is a straightforward combination of type (including a promotion of the author’s last Miss Jane Marple novel, 1976’s Sleeping Murder) and two elements quickly identifiable as appropriate to Poirot’s character: a gentleman’s hat and a fussily curled mustache (“very stiff and military,” to quote the author). No matter that the chapeau is a bowler (more synonymous with The Avengers’ John Steed), rather than the homburg that we customarily associate with Christie’s Belgian snoop.

Bantam (U.S.), 1981: Although he developed covers for novels by a wide variety of authors, including Raymond Chandler, Eric Ambler, Kingsley Amis, and John Fowles, Anglo-Scots painter/illustrator Tom Adams (1926–2019) is perhaps best remembered today for his artistically harmonious, late-20th-century lines of Agatha Christie paperbacks. From 1963 to 1980, he was under commission by Britain’s Fontana Books to devise cover imagery for Christie’s series works as well as her many standalones. During the early 1970s, he also fashioned fronts (most of them featuring wraparound scenes) for U.S. publisher Pocket Books. Interestingly, the first Poirot puzzler was a yarn to which Adams did not initially contribute art. So in the early ’80s, when American imprint Bantam bought some of his existing work to employ on Christie softcovers of its own, it repurposed for its version of The Mysterious Affair at Styles—shown above—a still-life tableau Adams had done for Fontana’s circa-1972 release of Three Act Tragedy, a Poirot novel that premiered in 1934. (The port glass and rose both figure into that tale.) Not until 2016 did Adams create a painting specifically for Styles, that edition being part of a hardcover boxed set that also included Poirot’s final outing, Curtain (1975).

Triad Granada (UK), 1982: An example of simplicity that doesn’t work. A pair of disembodied hands, a dripping vial of supposed poison, a sable background—was this someone’s Intro to Photography class submission?

Black Dog & Leventhal (U.S.), 2006: To no less degree than poison bottles, coffee cups have become elemental to Styles iconography. On this hardback cover, part of a set designed earlier this century by Liz Driesbach, we see such a vessel, with a silver spoon protruding. There’s nothing overtly ominous about this staging; yet the fact of the cup being overturned on its saucer suggests, subtly but effectively, that something is amiss. An elegant demonstration of dust-jacket messaging.

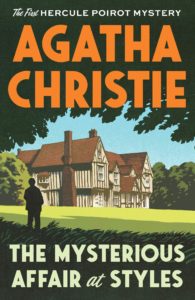

Vintage (U.S.), 2019: London-based illustrator and printmaker Chris Wormell was a rubbish collector, road sweeper, and postman before taking up wood-engraving in 1982. His self-taught talents have since been on display in children’s books, on greeting cards, and in advertising campaigns. Wormell has recently created fresh fronts to adorn Vintage paperback editions of several Christie novels. For The Mysterious Affair at Styles, he’s imagined Styles Court as a Tudor Revival country manse, replete with dark timbering, tall chimneys, and overhanging floors. As to who that silhouetted figure is in the foreground, well, it just might represent the reader, musing on the disconnect between this dignified abode and the intrigues it contains.

General Press, Kindle edition (U.S.), 2020: Did the designer here neglect to read Christie’s novel, and just guess that the Affair in its title alluded to a romantic entanglement central to the plot? Photoshopping a steaming cup of java into the lower corner only makes the whole presentation look more absurd.

___________________________________

FOREIGN-LANGUAGE EDITIONS

___________________________________

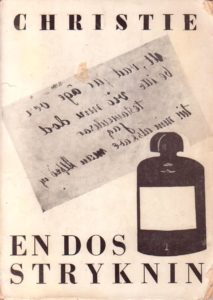

Albert Bonniers (Sweden), 1929: This edition’s title translates as A Dose of Strychnine, so it’s no surprise that its principal jacket image should be another poison container. Beside it lies what seems to be a short missive, perhaps one of the notes—anonymous and otherwise—that affect the actions and alibis of this story’s players. On the other hand, it could be part of a revised last will and testament that Emily Ingelthorp is thought to have written, but which has gone missing.

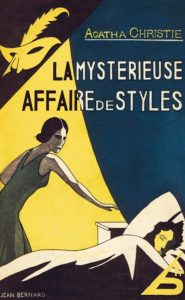

Le Masque (France), 1932: For someone who’s often defined—not wholly appropriately—as a concocter of cozy whodunits, Christie has spawned her fair share of book covers that lean more toward the suspenseful. Case in point: this 2019 facsimile of a striking, ’32 Styles front, hinting at a woman’s hand behind the widow’s slaying.

Mondadori (Italy), 1932: Your guess is as good as mine regarding why the publisher renamed Poirot’s debut investigation Un Delitto Misterioso A Stylen Court (A Mysterious Crime at Stylen Court). “Stylen”? Again we find here a woman—or at least her looming shadow—being identified as the elderly Mrs. Inglethorp’s killer…which may or may not be true. The matching bedside candles are a nice, creepy touch, giving the scene a portentous funereal quality; they don’t exist in the book, however, which has John Cavendish and others entering his stepmother’s room, then firing up gaslights for enhanced illumination.

Edizioni Argo (Italy), 1933: When in doubt, throw as many symbols of death as possible onto the cover. A white-haired crone? An hourglass (implying that her time is short)? A casket? Sure, why not. It’s only amazing the artist resisted also squeezing a skull and crossbones into this mix.

Scherz (Germany), 1970 and 1980: The first of these is decidedly the more dreadful, with Poirot looking like a mad bomber rather than a perspicacious sleuth. And who’s the would-be dominatrix with him? I can’t envision being seen with such a book in hand. Not that the second cover here is much better. Yes, playing cards make a late appearance in Styles, when the protagonist patiently constructs houses from them while trying to concentrate his “little grey cells” on the circumstances of the murder. But why feature what must be Poirot’s face on them, then ink a cross or an X on the back of one? The message communicated is that the detective perishes in these pages, or is in some manner threatened, which is not at all true.

M. Mizrachi (Israel), 1973: Is the blonde dominating this Hebrew-language release of Styles the same comely creature from Barye Phillips’ 1951 paperback? She’s slightly more dressed now, in a flimsy nightgown rather than a robe threatening to bare her panoply of assets. But she’s a similar conundrum, no more easily associated with this story than is the swarthy fellow at stage left, who—with his broad-brimmed hat, overcoat, and cigarette—looks like he’s stumbled in from a hard-boiled detective mystery. Were it not for that corpse on the bed, one hand flung toward the nightstand, it would be hard to know this book’s identity.

Bonniers (Sweden), 1984: Now, that’s more like it! An unmistakable Poirot, with a walking stick and again wearing a bowler, gazing at what is undoubtedly Styles Court. Curious, though, that the house seems to exist in a picture frame, as if separate from the world of this vain retired policeman or unreal in its way. The symbolism is unmistakable, for didn’t Poirot novels invite that character to enter a realm with which he was unfamiliar, then ask him to set its neoteric disorder to rights?

Le Masque (France), 2012: Again, artistic restraint delivers favorable results. Just an open door, with the light shining in, from which we may infer that a space has been invaded: Emily Inglethorp’s bed chamber, presumably, though it’s not clear whether the occasion for such encroachment was to drug her…or rescue her.

RBA Libros (Spain), 2014: My principal complaint with this cover is that it’s so ridiculously generic. Its photograph offers us the interior of what’s either a large vintage home or a dignified hotel. That print rests atop an unrelated, indecipherable, reddish-gold surface. There’s no more in the way of art. Except for the byline and titles, and the message indicating that this edition—part of a revised RBA set of Christie paperbacks—commemorates the 125th anniversary year of Agatha Christie’s birth, this could comfortably front any multitude of novels, and not merely mysteries. It provides a lackluster introduction to Hercule Poirot’s inaugural private investigation, and does no justice to Christie’s place in the literary firmament. Statistics tell us her books are “outsold only by the Bible and Shakespeare,” and that they “have been translated in more than 100 languages, making her the world’s most-translated writer.” Making more history, Poirot was the first fictional character to win a front-page obituary in The New York Times, following the publication of Curtain. For its impact and longevity, didn’t Styles merit better than this humdrum packaging?