The Anderson Tapes is a heist movie, there’s no doubt about that. It depicts the typical thrills and shenanigans of the genre, beginning when a charismatic ringleader assembles a colorful crew of criminal masterminds with varied skills, to pull off one last job. It is, to say the least, a good time at the movies. When it was released in 1971, it did quite well at the box office, grossing $5 million. But it received mixed reviews, and if it is remembered today at all, it is for presenting the world with the first mainstream film performance of Christopher Walken.

But, if you really listen to The Anderson Tapes, then you will learn that it is bolder than a traditional heist movie. It delivers to its audience the usual pleasures of the heist genre, but those audiences are not the only ones listening in. There are eavesdroppers inside the film, too, bugging the thieves as they hatch their top-secret plans. Through its blending of non-diegetic and diegetic viewing, The Anderson Tapes delivered understated sociopolitical commentary on an important issue: the increasing pervasiveness of surveillance within American society, as well as the failure of law enforcement to act positively on the intelligence it gathers.

Director Sidney Lumet establishes the importance of electronic surveillance in the first shot of the film. It features a TV playing a recording of convicted safecracker John Anderson (Sean Connery) as he tries to offer an explanation for his crimes in a prison group therapy session. Already, surveillance equipment is represented as having captured Anderson’s image against his will. We watch him glumly watch himself on the TV with his fellow prisoners. But the next few moments feature Anderson regaining a sense of power as a prison official declares that Anderson’s ten-year sentence is ending. We learn right away that the newly freed Anderson plans to go back to his old tricks.

But right away, Lumet undercuts Anderson’s good luck in a following scene, in which he visits his girlfriend Ingrid Everleigh (Dyan Cannon). As Anderson enters the fancy apartment set up by her married boyfriend Werner (Richard B. Shull), Lumet tracks the camera to reveal a wiretap in the room. An agent for the “Peace of Mind” private investigation agency is, at that moment, in the building’s basement, where he is recording the apartment, and incidentally, Anderson having sex with Everleigh. The agent’s intention is to find evidence of Everleigh’s infidelity, but he unwittingly records Anderson telling Everleigh of his next criminal exploit: to rob her upper-class apartment building.

But right away, Lumet undercuts Anderson’s good luck in a following scene, in which he visits his girlfriend Ingrid Everleigh (Dyan Cannon). As Anderson enters the fancy apartment set up by her married boyfriend Werner (Richard B. Shull), Lumet tracks the camera to reveal a wiretap in the room. An agent for the “Peace of Mind” private investigation agency is, at that moment, in the building’s basement, where he is recording the apartment, and incidentally, Anderson having sex with Everleigh. The agent’s intention is to find evidence of Everleigh’s infidelity, but he unwittingly records Anderson telling Everleigh of his next criminal exploit: to rob her upper-class apartment building.

Lumet and screenwriter Frank Pierson (who would later collaborate on Dog Day Afternoon) took this film’s jaded view on the pervasiveness of electronic surveillance from its source material, Lawrence Sanders’s debut bestseller of the same name for which he won the Edgar Award for Best First Novel in 1970. Lumet saw this novel as more than fodder for a commercial hit. Many of his films have strong political stances that reflect his progressive political beliefs. His first film critiqued racial prejudice in the criminal justice system (12 Angry Men) and other films that he had made before The Anderson Tapes covered such serious subjects as nuclear warfare (Fail-Safe), the Holocaust (The Pawnbroker), and the brutality of a British military prison during World War II (The Hill). Lumet had also co-directed a documentary called King: A Filmed Record…Montgomery to Memphis about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., whose suffering of intense surveillance from the FBI (one of the groups depicted as using wiretaps in The Anderson Tapes) is the subject of the recent documentary MLK/FBI. The fact that Lumet wanted to keep the political implications of Sanders’s book in his adaptation is evident from one of the few references he makes to it in his classic book Making Movies. Lumet notes in an early chapter that for every film he made, he would give it a theme that would influence every technical and narrative decision he made as a director. The theme that he gave The Anderson Tapes was “the machines are winning.”

This theme adds an additional layer of conflict to The Anderson Tapes that is especially relevant in our modern Internet age. That conflict is between an “analog man” – Anderson is a safecracker and most of the idiosyncratic people that he recruits to his crew have manual labor jobs – and a “machine man,” a term which could describe any of the faceless law enforcement agents operating within the vast array of intelligence-collecting rings which inadvertently surveil Anderson and his crew.

This celebrates working-class physical labor and savvy over high-tech, white collar snooping. But the fact that these listening and recording devices are everywhere suggests that, even if Anderson pulls off his con, it will merely amount to a victorious battle in a lost war. The interesting thing about The Anderson Tapes is that it releases Anderson into a world in which “surveillance technologies” have become part of its very infrastructure. Surveillance is no longer a feature of the system, it is the system, which calls to mind nineteenth-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s “Panopticon,” which was a building built to be its own surveillance technology. Although, in this film, the “panopticon” isn’t just one structure. Instead, it is an entire city.

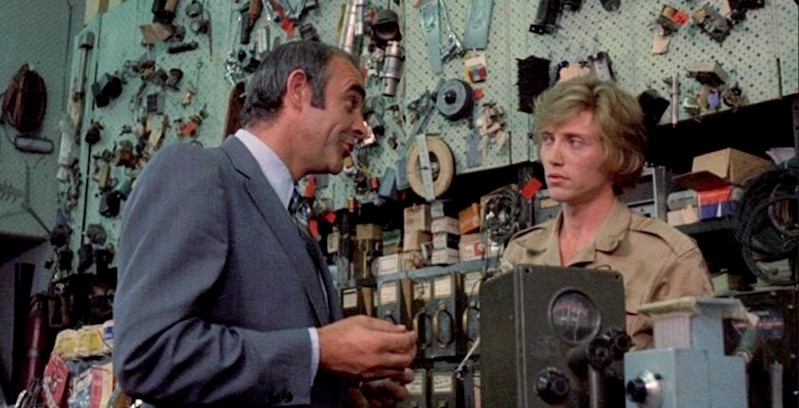

Surveillance is no longer a feature of the system, it is the systemLumet and Pierson further develop their world in which an enhanced version of The Panopticon exists as Anderson goes about recruiting the members of his crew – all of whom are under some type of surveillance from their federal or state government. Mobster Pat Angelo (Alan King) finances the heist as the Treasury Department and the FBI go to great lengths to record his conversations. The NY State Narcotics Commission has Anderson’s friend from prison/crew member The Kid (Christopher Walken) under surveillance because he used to be a drug dealer. The “House Internal Security Committee” films Edward Spencer, one of two Black members of Anderson’s crew, because he happens to live above the local chapter of the Black Panther Party. These scenes often feature pieces from the synthesizer-laden score by Quincy Jones (his third for Lumet after The Pawnbroker and The Deadly Affair) that sound like they were beamed in from a science fiction film that takes place in a world where machines have taken over the planet.

What is especially interesting is how the film’s subtle sociopolitical commentary functions within the confines of a heist film. Lumet and Pierson include no long, moralizing monologues to denounce electronic surveillance. Rather, they take scenes that would belong in a classic heist film and attach a moment or two of someone filming or recording it in the way that someone would fasten a wire to an informant. Some would argue that this prevents the film from living up to its potential as a political statement but smuggling these ideas into a heist film probably guaranteed them a wider audience.

This film’s spirit of subtle subversion extends to how many of its actors play against type and, in doing so, tamper with their legacies of recorded images which form a type of “file” on them similar to the files that the FBI kept on people in real life. At the time of this movie’s release, Connery was most famous for playing the suave James Bond. But in The Anderson Tapes, Connery is a rough-edged anti-hero who freely admits that he believes the world is “dog eat dog, and I want the first bite.” This movie also features the last on-screen film performance by Margaret Hamilton, most famous for playing The Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz. Instead of playing a monstrous villain, Hamilton plays a befuddled victim of the robbery who is so proper that she offers to make coffee for Anderson’s crew. In addition, today most audiences know Walken as a sinister-looking elder statesman of American acting, but he was only 27 when he played the aptly named “The Kid.”

This was Walken’s first appearance in a mainstream American film, which gave it the right to boast the now incongruous credit “and introducing Christopher Walken.” His shockingly fresh-faced looks aid his performance as the crew’s youngest member who is prone to lines such as “America! It’s so beautiful, man. I want to eat it.” His performance and the many other subversive casting choices play into the pattern of The Anderson Tapes continually subverting the heist movie’s reputation as “simple entertainment.” In doing so, it reveals the spirits of wealth redistribution and “down with the rich” (or, maybe in The Kid’s case, “eat the rich”) sentiments that are built into the very fabric of the genre.

It is worth noting that not every casting decision in The Anderson Tapes is effective. One member of Andersons’s crew is Tommy Haskins, a gay antiques dealer who will fence the stolen goods acquired in the heist. When Anderson first visits Haskins in his antique shop, it becomes clear that he is the type of stereotypical gay character (played by heterosexual actor Martin Balsam) that unfortunately populate many American films, even to this day. The repeated use of homophobic slurs to describe him as well as Balsam’s performance (which Roger Ebert called “swishy”) make the film a kind of time capsule of intolerance, but it also foregrounds the victimization of the LGBTQ+ community two years before the American Psychiatric Association took homosexuality off of its list of mental illnesses/sicknesses, but before the AIDS epidemic led the same community to become even more degraded and ignored by mainstream society.

In addition, law enforcement’s surveillance of him is at least partly based on his sense of “otherness” (one of the people who requests a wiretap on him does so by referring to him with a homophobic slur) that is similar to how the federal government only surveils Spencer because he lives above the headquarters of the local chapter of the Black Panther Party (an organization Lumet supported, himself, by hosting a fundraiser for their legal defense fund a week before Leonard Bernstein’s infamous gathering that Tom Wolfe described as being for the “radical chic”). This cleverly represents the tunnel vision of law enforcement; Anderson is on tape planning a heist, yet two of his team members are found suspicious not for their connection to his criminal plans, but for being gay and Black.

This collective failure of characters in The Anderson Tapes to recognize and act on intelligence is more relevant than ever in the wake of the intelligence failures that exacerbated the storming of the Capitol on January 6th. Multiple federal and state agencies consistently fail to regard Anderson as a person of interest to the extent that a Treasury department agent says “we don’t care about him” when he shows up on government surveillance for the first time. The governmental agents fail to use their elaborate webs of surveillance to learn that the robbery, planned by a man they repeatedly refer to as an “unidentified Caucasian male,” is going to happen. Their narrow focus on trying to tie the people they surveil to other crimes—Angleo for mafia related shenanigans, The Kid for drug dealing—is so intense that they totally miss the signs that their connections to that “unidentified Caucasian male” (a subtle and underdeveloped acknowledgement that white men can get away with crimes at a rate greater than their counterparts of color) will result in a crime that they were not expecting. Their tunnel vision is so strong that a young boy in a wheelchair is able to do more to foil the crime with a simple radio than several government agencies can do with state-of-the-art equipment. Late in the film, when police captain Edward X. Delaney (a minor character from the novel whom Sanders would turn into the protagonist of a spin-off book series that began with The First Deadly Sin) discovers a wiretapping machine, he seems to speak about all of the massive yet unconnected surveillance networks we have been watching throughout the movie when he says, “An operation this size, you think you’d get some information!”

But using information to make immediate arrests of Anderson’s crew before the heist based off of information or intelligence isn’t the main goal of these surveillance rings. Instead, the film seems to argue that they exist to gather intelligence so that one day, perhaps, they might make an arrest after learning as much about their targets as they can. Until that day, this technology and the “machine men” that operate it will subtly reshape the world. Their great influence even affects the mind of Pop, an elderly criminal who spent 40 years—a time period in which electronic surveillance equipment rapidly developed—in the same prison as Anderson. During the heist Anderson gives Pop the job of pretending to be the doorman so he can monitor the security camera feed on the lobby’s array of TVs. Flush with gratitude for Anderson’s help, and newly indoctrinated into the world of technology that barely existed before he went to jail, Pop sputters out the greatest compliment he can think of to thank Anderson: “You look swell on the TV!”

The Anderson Tapes would receive some positive reviews, but they mostly focused on its entertainment value as opposed to its subtle sociopolitical commentary. Ebert praised how it worked “very, very nicely” as an example of “the Big Heist movie” but noted that he felt “the only serious structural flaw in the movie involves the emphasis on electronic surveillance.” Andrew Sarris, the venerated critic praised for bringing the auteur theory to America, went a step further in his distaste for The Anderson Tapes by complaining “I thought there were about 11 good minutes in it, and the rest confused and uncertain.” Like Anderson and his team, these critics disregarded the all-encompassing and dangerous panoptic surveillance that surrounded them in favor of completing their narrow tasks. Their mixed reviews would help cement the popular perception of The Anderson Tapes as nothing more than an entertaining entry in the heist genre.

But while this film would fade from the public view, it would, in a way, have the last laugh. The Anderson Tapes had its premiere in New York City on June 17, 1971. A year to the day later, police would arrest five men for breaking into the Watergate Complex to repair illegal wiretaps that they had planted inside of the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters. It seems fitting that a film so far ahead of its time would only see the establishment of its true legacy—as the first major American film to portray how pervasive electronic surveillance had become—a year after its release.