In a year like 2020, it’s no wonder that people have been turning to both historical fiction and genre fiction in record numbers. We all need an escape, and sometimes the best escape from the present is into the worst parts of the past. This year brought a number of thrillers set in the 17th century, a trend that continues in 2021’s numerous witch-themed releases, and given the brutality of that epoch, it’s no wonder that Early Modern stories resonate at the moment. There were also plenty of Victorian mysteries, early 20th century intrigue, and mid-20th century suspense. It’s a difficult task to settle on the best of anything, and with historical fiction, the particular eras one is attuned to reflect the reader’s own head space more than the genre at large, but many of the below works are concerned with isolation, alienation, confinement, and loneliness: all themes that speak to today’s ills, in the language of the past.

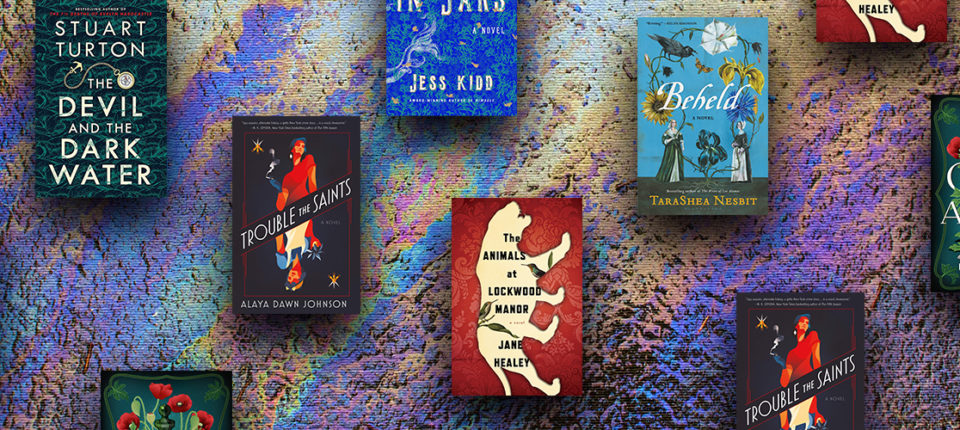

TaraShea Nesbit, Beheld (Bloomsbury—comes out March 17th)

Setting: 1630 Plymouth, Massachusetts

I’m a huge fan of historical crime fiction, especially those books that manage to tell a compelling story while still immersing the reader in the thoughts and opinions of the time. TaraShea Nesbit’s Beheld begins with a murder on American soil ten years after the arrival of the Mayflower. It’s the first murder to occur in the fledgling colony, and the crime has its roots in the rivalry between an Anglican family and their Puritan neighbors, made deadly by the arrival of an interloper. Perfect for fans of Women Talking. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads senior editor

Stuart Turton, The Devil and Dark Water (Sourcebooks)

Setting: 1634, the Open Sea

Sherlock Holmes meets the Dutch East India Company in Stuart Turton’s latest wildly creative foray into fiction. A mysterious presence haunts a trading ship carrying passengers, cargo, and one VIP—standing, here, for Very Important Prisoner. The Sherlockian detective onboard is stuck in the brig, moping over his lack of fashionable clothing when he’s not steering his brutish sidekick’s investigations into their ill-fated voyage. The names alone make this one worthwhile. Just something about the Dutch… –MO

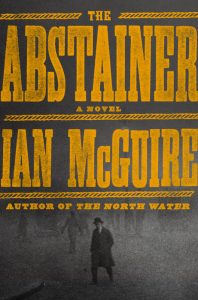

Ian McGuire, The Abstainer (Random House)

Setting: 1867 Manchester

In 1867 Manchester, revolution and murder will tear an Irish family apart, as one member sides with the Fenians and the other works to take down the budding rebellion from the inside. Featuring rich detail and vividly drawn characters that perfectly embody their milieu, The Abstainer is essential reading for all fascinated by the intersection of crime and history. –MO

Jess Kidd, Things in Jars (Atria)

Setting: Late Victorian Era London

Jess Kidd’s truly weird supernatural thriller really delivers on the title—there are so, so many things in jars. Big things, little things, very creepy things, and more. There’s historical fiction that’s chock full of the realistic details of the time, and then there are historicals that capture the essence, the mindset, and the atmosphere of the time. This is one of the latter. Bridie Devine, a resurrectionist-turned-detective who knows how to read bodies and find missing people, is on the case to track down a stolen little girl with strange powers—if the circus impresarios and bottling surgeons don’t find her first. Oh, and for all the Patricia Highsmith fans out there, I have one word for you: snails. –MO

Lydia Kang, Opium and Absinthe (Lake Union)

Setting: 1899

Lydia Kang is one of the great virtuosos of the crime genre—a doctor and author, she splits her writing between historical mysteries, popular history, and young adult scifi. Opium and Absinthe takes place in 1899, where an opium-addicted heiress investigates the mysterious death of her sister by puncture wound, even as the popularity of Bram Stoker’s Dracula soars. Well-researched, grounded in the past, and ultra-relevant to today’s opioid epidemic, this one is not to be missed. –MO

Gary Phillips, Matthew Henson and the Ice Temple of Harlem (Agora)

Setting: 1920s Harlem

Perhaps it’s merely the restlessness of quarantine, but 2020 seems to have heralded the return of classic adventure fiction. Matthew Henson and the Ice Temple of Harlem features Black polar explorer Matthew Henson, denied credit for his explorations for much of his lifetime, as he spends his golden years living the quiet life. That is, until a new quest plunges him in the heart of the Harlem Renaissance for a perfect jazz age mystery. –MO

Alaya Dawn Johnson, Trouble the Saints (Tor)

Setting: 1940s Manhattan

Alaya Dawn Johnson’s Trouble the Saints is a vast, scintillating, slightly fantastical, hardboiled noir set in WWII-era Manhattan. The novel’s main conflict—a betrayal plot—plays out alongside the conflicted decisions of its many torn characters. Phyllis, a light-skinned Black woman who passes for white, is an impossibly adroit knife-wielding assassin (she has “saints’ hands”—a magical ability that is found rarely, but only in Black and Brown People of Color), and while she works for a dangerous Russian mob boss named Victor, she only takes jobs that she feels are justified, killing people who “deserve” it. Her love Dev, a British, Indian, and Hindu undercover police officer who works for Victor, is facing a crisis about the work he does and who he does it for (a department who won’t accept him, ever, really), as he attempts to use his own magical gift (he can read potential threats with his hands). Phyllis’s close friend Tamara, is a tarot-reading snake-dancer, who, unlike Phyllis, chooses not to conceal her Blackness, but exoticize it as she ignores the bloodshed wrought by her employer Victor, to profit from white-controlled society.

Knowing its characters are all trapped (in a way that dovetails with the paradox of Black identity as explained by Franz Fanon—as being fundamentally formed by and subject to definitions and structures of success, power, and failure built and controlled by hegemonic white culture), the novel asks questions about complicity in and resistance to white violence and oppression. It is a haunting, beautiful, sleek story—about coming to terms with who we are, and who made us that way. –Olivia Rutigliano, Lit Hub and CrimeReads Staff Writer

Jane Healey, The Animals at Lockwood Manor (HMH)

Setting: WWII English Countryside

In this lush historical novel, a museum curator heads to a country manor with a collection of rare fossils and specimens, ready to do whatever it takes to protect her beloved curiosities from the Blitz. What she doesn’t anticipate is difficulty with the boorish overlord of the manse, who’d like to treat the museum’s collection as it were his own assemblage of hunting trophies, or the possible presence of a ghost, who may or may not have killed the previous lady of the manor. She also doesn’t expect the beautiful daughter of the manor to take such an interest in the fossils—or in their curator. –MO

Håkan Nesser, The Summer of Kim Novak (World Editions)

Setting: 1960s Sweden

I love Nesser’s quirky and compelling Van Veeteren books, but it’s a treat to see him branch out in this novel set in the 1960s in rural Sweden. In Summer two boys, Erik and Edmund, have a collective crush on a teacher who resembles the actress Kim Novak. But this coming-of-age story veers into a mystery before too long, with Nesser’s trademark knack for suspense. –Lisa Levy, CrimeReads contributing editor

Jasmine Aimaq, The Opium Prince (Soho)

Setting: 1970s Afghanistan

The Opium Prince takes place at a crossroads in Afghani history, so perhaps it’s appropriate symbolism that the greatest trauma to befall its characters is a deadly car accident. In Aimaq’s debut, an Afghani-American government worker is tasked with convincing the locals to grow something other than poppies, but there’s plenty of opposition to his plans from warlords even before the Soviet invasion and rise of the Taliban make his efforts a moot point. While the mid-1970s might not seem like history to some, we need origin stories as an antidote to the pervasive notion that the Middle East has always been beset by war, and to the even more pervasive notion that this is somehow not our fault. –MO