“I once received a lovely letter from a lady who told me how she had got this book [of mine], made herself a cup of tea and drawn the curtains because it was a dismal cold day. Then she’d set a fire in the fireplace and sat down and read my book. Isn’t that a nice goal for a writer to think about? It certainly keeps me at my typewriter.”

—Mystery author Charlotte MacLeod in “Murder, She Writes,” Interview with Peter Gorner of the Chicago Tribune, 11 February 1988

His attack was lightning fast. Whitey seized [Debbie Davis] by the throat with his hands and began to shake her like a rag doll. Debbie, gasping for breath, was dying….

Whitey was still not done with the ghastliness. He handed Stevie a pair of pliers and instructed him to yank the teeth from the lifeless Debbie Davis to hamper authorities from ever being able to identify her through dental records….

Whitey and Stevie wrapped Debbie in plastic, then dragged her body upstairs and out into the late afternoon light. They threw the bundle into the trunk of a car and drove off. Later in the evening they headed to what would become known as the Bulger burial ground—a stretch of marshland along the Neponset River, beneath a bridge connecting Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood to the city of Quincy.

—Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill, Whitey: The Life of America’s Most Notorious Mob Boss (2013)

INTRODUCTION: Lady and the Tramp

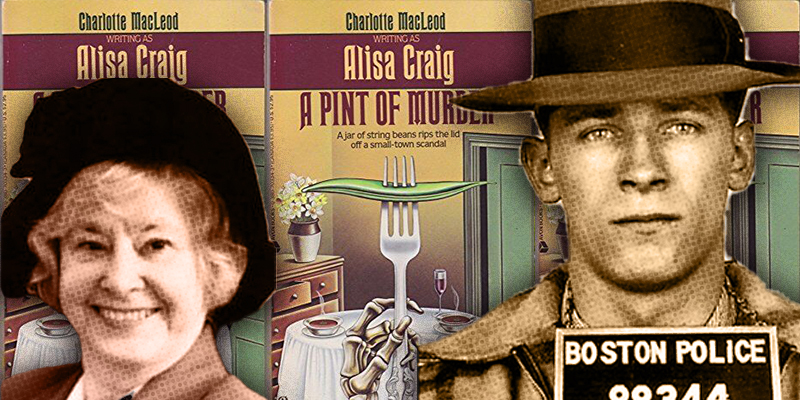

Charlotte MacLeod she of the white gloves and hats and impeccable grammar

Charlotte MacLeod she of the white gloves and hats and impeccable grammar

Over a period of two decades period—1978 to 1998, to be precise—Canadian-American detective novelist Charlotte MacLeod (1922-2005) published thirty-two crime novels representing no less than four mystery series, all of which to the delight of her fans were brought back into print in the US a decade ago by Mysterious Press/Open Road. Today MacLeod, an Edgar-nominated mystery writer, is considered one of the founding mothers of the modern cozy mystery. As those who wrote about MacLeod were found of noting, her books “eschewed gore, graphic violence, sex and vulgar language” while indulging in “a little romance and a lot of laughs.” (See the author’s obituary in the LA Times.) For her part MacLeod pronounced herself a backwoods Michael Innes” and an author of manners novels with murders, in the style, albeit folksier, of Dorothy L. Sayers.

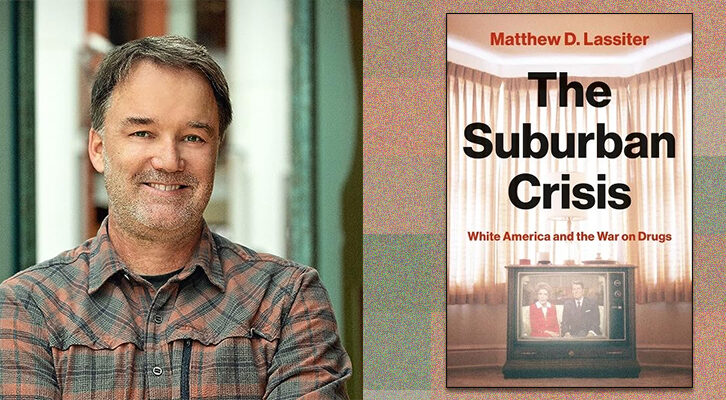

How surprising it is, then, that in real life Charlotte MacLeod had a close family connection to the notorious Boston mobster James Joseph “Whitey” Bulger (1929-2018), leader in the Seventies and Eighties of the Winter Hill Gang, a confederation of Boston area organized crime figures of mostly Irish and Italian descent. The late Bulger, a one-time mob informant who at the time of his demise in 2018 at age eighty-nine was serving consecutive life sentences for the slayings of eleven people which he committed while informing to the FBI (and that was only part of his suspected death toll) was savagely beaten to death in prison. His features after the attack were said to have been so brutally battered as to be unrecognizable. It was a violent end to a violent life.

Just how far removed Whitey Bulger’s real life crimes (not to mention his own horrible quietus) were from those found in the comfy pages of cozy mysteries this line about Whitey from his New York Times obituary indicates: “[H]e shot men between the eyes, stabbed rivals in the heart with ice picks, strangled women who might betray him and buried victims in secret graveyards after yanking their teeth to thwart identification.”

Felon in a fedora: Whitey Bulger at the start of his life in crime in 1953

Felon in a fedora: Whitey Bulger at the start of his life in crime in 1953

While there are, to be sure, bizarre and nasty murders in Charlotte MacLeod’s books (in Wrack and Rune, for example, a man is killed by having his face shoved in a bucket of quicklime, something you could imagine happening in a Martin Scorsese film), it is all done decidedly tongue in cheek by the Cozy Crime Queen. In Whitey Bulger’s world, on the other hand, tongues were more likely to have been found outside of cheeks, having been bloodily separated from bodies. Yet Whitey Bulger’s highly respected brother William rather incredibly ascended, during the period of Whitey’s commission of his ghoulish carnival of crimes, to become president of the Massachusetts State Senate and the University of Massachusetts. William Bulger resigned as president of UM only under pressure from then Governor Mitt Romney and others, after the media spotlight focused on his relationship, about which he had not been altogether forthcoming, with his brother Whitey, who was then a fugitive from federal justice. The truth is that, despite all of his well-merited notoriety and a multiple murderer, Whitey himself remained a folk hero to many in his old South Boston stomping grounds. So perhaps the Charlotte MacLeod-Whitey Bulger connection is not so incongruous after all.

QUEEN OF THE COZIES

Baptist church at St. Stephen, New Brunswick where Charlotte McLeod’s father Edward Phillips MacLeod, grew up

Baptist church at St. Stephen, New Brunswick where Charlotte McLeod’s father Edward Phillips MacLeod, grew up

Although she grew up in the United States on the South Side of Boston, Charlotte Matilda MacLeod was born on November 12, 1922 in another, rather gentler country: Canada. Specifically she first saw light of day in a flat above a grocery store in the quiet little village of Bath, in the far western section of the maritime province of New Brunswick, fewer than twenty miles from border with the American state of Maine. Charlotte’s parents—Baptists Edward Phillips “Phil” MacLeod, a telegraph operator turned plumber with a seventh grade education and son of lumber surveyor Alexander MacLeod, and Mabel Maude Heyward, daughter of farmer and mail carrier Clarence Edgar Heyward—had wed two years earlier; and Charlotte had a slightly older brother, Walter Hughes MacLeod. The young family moved to Massachusetts in 1923, when Charlotte and Walter were toddlers, settling in Weymouth, a city on the South Shore of Boston. There Phil continued lucratively to ply the plumbing trade as two more children, daughters Helen Aldyth and Alexandria Jean, were born to him and Mabel.

Also moving to the Boston vicinity at about the same time was Phil’s sister Marion Cecilia MacLeod (1889-1982), wife of John Mackay, a former Halifax, Nova Scotia accountant who in Boston worked as a librarian/archivist for the Boston Herald newspaper. Marion Mackay likely was the 91-year-old aunt to whom Charlotte MacLeod affectionately dedicated A Pint of Murder (1980), which is set in New Brunswick and is the first of her Alisa Craig mystery novels.

Brotherhood Bible Class, St. Stephen Baptist Church, 1916 Possibly Charlotte MacLeod’s father Phil, then 19, was a member

Brotherhood Bible Class, St. Stephen Baptist Church, 1916 Possibly Charlotte MacLeod’s father Phil, then 19, was a member

Among the children of John and Marion Mackay was daughter Ailsa, ten years her cousin Charlotte’s senior and a business school graduate and stenographer. It was from Ailsa Mackay that Charlotte derived the first half of her mystery pseudonym Alisa Craig, the second half of which was drawn from “Ailsa Craig,” a spectacular island—actually the plug of an extinct volcano—off the coast of Scotland. (Certainly the MacLeods were a very Scottish family, like so many others in New Brunswick.) According to mystery writer Dean James, however, Charlotte told him at a book signing that her publisher deemed “Ailsa too strange and insisted on Alisa.”

the house on Gilmore Street

the house on Gilmore Street

In the 1930s the MacLeod family moved into a 966-square-foot white clapboarded house, originally built in 1918, on a large lot on Gilmore Street in Weymouth. When this modest house was sold recently (for nearly a half million dollars), the realtor itemized it as having a kitchen, 9×12, dining room, 9×10, living room, 11×11, master bedroom, 12×13, second bedroom, 7×11 and bonus room, 5×7, plus a single bathroom, an enclosed front porch, a basement laundry, a detached single car garage and a storage shed. In the 1930s Charlotte and her slightly younger sister Helen presumably would have shared the larger upstairs bedroom, while Walter would have occupied the smaller upstairs “bonus room.” Baby sister Alexandria did not come along until 1937, when Charlotte was fifteen and a few years from leaving the family nest for college in Boston.

the house in Jamaica Plain

the house in Jamaica Plain

The Mackays lived about a dozen miles away from their MacLeod kinfolk, in a pretty white Italianate house built in 1860 in Jamaica Plain, a neighborhood in west Boston. Besides Ailsa, the children in the Mackay family included Donald Alexander Mackay, a graduate of the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and an accomplished artist and illustrator in the second half of the twentieth century. (He is best known for the 1987 book The Building of Manhattan.) Also living with the Mackay family in 1940 was Charlotte’s widowed grandmother, Matilda Lenora (Hughes) MacLeod, daughter of Canadian Baptists Edward Phillips Hughes, a native Welsh house carpenter and Charlotte Cecilia Yerxa, daughter of a native Dutch farmer. So Charlotte’s family was an admixture of Scottish-English-Welsh-Dutch nationalities, but seemingly in religious persuasion it was 100% Baptist.

You might be surprised to learn there were so many Baptists in Canada (whether of Scottish, English, Welsh or Dutch extraction), yet that remarkable mystery plagiarizer and all-round scoundrel Maurice E. Balk masqueraded for a time in the 1920s as a Baptist minister in Nova Scotia, another of the maritime provinces. For all I know Balk might have ministered to credulous MacLeods and Mackays, Heywards and Hughes, and even the odd Yerxa.

Charlotte, or “Charlie” as she was familiarly known, graduated from Weymouth High School in 1940, as the country neared joining the world at war. An attractive, dun girl, though seems to have something of a squint, “Charlie” made the honor roll every year, belonged to the French Club and was junior and senior class spelling been champion. She also played the part of “Olga” in the school’s senior play Tovarich, a stage comedy from 1933 by French playwright Jacques Deval, first performed on Broadway in an English adaptation in 1936, about two exiled Russian aristocrats who take jobs an domestic servants in between-the-wars Paris. Two grades ahead of “Charlie” at Weymouth High School was her brother Walter, or “Mac” as he was nicknamed, who rather resembled a cross between his sister and Mr. Rogers. He was a tall and gangly youth, at 6’2” and 140 pounds, with brown hair and hazel eyes. (He shared his sister’s squint, which can be a hereditary trait, as well as her infectious grin.) Already Walter, when he was not in school, industriously assisted his father (who himself was blind in one eye) in the family business: Gilmore plumbing and heating, developing especial expertise in the heating end.

During the Second World War, when Walter and the MacLeod’s male Mackay cousins fought the original Axis of Evil overseas (Walter was a POW in the Philippines), Charlotte attended the Art Institute of Boston (now merged into Lesley University). After the war, while residing at an apartment in an 1885 red brick building on Beacon Bill, she worked, like her Cousin Donald, as a commercial artist, in her case in the employment of the catchily-named Stop and Shop supermarket chain. However, in 1952, about the time Whitey Bulger was first arrested in Beantown, Charlotte accepted a copy writing position with a Boston advertising firm. Three decades later she retired at the age of sixty, at which time she had risen to a position as vice-president. Thenceforward she found plenty of things to occupy her time, including writing no fewer than four fictional mysteries series.

In the Fifties, Charlotte MacLeod worked as a commercial artist for Stop and Shop supermarket chain.

In the Fifties, Charlotte MacLeod worked as a commercial artist for Stop and Shop supermarket chain.

Like PD James, another accomplished career woman turned mystery author, Charlotte MacLeod saw her success in crime writing come later in life, but she did very well for herself in the field from then onward. James’ great breakthrough came with her transatlantic bestseller Innocent Blood (1980), published when she was sixty years old, after eighteen years of periodic crime writing on her part. Only two years younger than James, MacLeod concurrently enjoyed mystery writing success which was less spectacular but very steady.

Perhaps part of Charlotte’s criminous inspiration came from her father Phil, who while still just a teenager in the first decade of the twentieth century was tapped, in spite of his diminutive 5’5” stature, by Sherriff Frank Hogan of the town of Houlton, Maine to become his unpaid deputy. “If things were quiet at the Western Union office and Hogan needed help to calm some overly enthusiastic celebrators at Jake’s saloon, he sent for young MacLeod,” reported Phil’s obituary in the Boston Globe. “The sheriff’s young deputy packed an old Harrington and Richardson .38 caliber revolver, and when he arrived on the scene, folks took him seriously.” In 1971, a year before Phil’s death, Charlotte published a book, Brass Pounder, about her father’s colorful youthful adventures, in which she told of them firsthand, through Phil’s voice.

Seven years later, in October 1978, MacLeod, then fifty-five, published Rest You Merry, the first of her Peter and Helen Shandy series of mysteries, headlined by a professor of horticulture and his librarian wife at the fictional Balaclava Agricultural College in Massachusetts. The next year came The Family Vault, the first of her “Boston Brahmin” milieu mysteries with genteel Sarah Kelling and her art expert beau Max Bittersohn, while 1980 saw her initial “Alisa Craig” Canadian Mountie Madoc Rhys mystery, A Pint of Murder, set as mentioned in rural New Brunswick, and 1981 the first of her Grub-and-Stakers mystery series, also set in rural Canada.

Amazingly MacLeod kept all four of these series going, like a juggler twirling a multitude of plates, until 1996, 1998, 1992 and 1994 respectively. Only the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in the late 1990s put an end to the author’s impressively prolific, popular and critically praised crime writing career. MacLeod died at the age of eighty-two in 2005 in a nursing home in Lewiston, Maine, a state which she had made her home for the previous two decades. Until her health failed she dwelt at a 200-year-old house, a quaint former inn, in the small town of Lisbon Falls.

in honor of Charlotte MacLeod a plate of yummy Joe Froggers most certainly made with molasses

in honor of Charlotte MacLeod a plate of yummy Joe Froggers most certainly made with molasses

Charlotte’s brother Walter, a member of the Scottish Rite Bodies and the National Rifle Association, former president of the Braintree Rifle and Pistol and Club, a Master Mason and “accomplished ritualist” and an avid gardener and “inveterate cribbage player,” died three years after Charlotte in 2008, while still living in Weymouth, where he had been employed by the city for thirty-five years as a heating engineer. Their baby sister, Alexandria, died five years after Walter in 2013. During her sister’s years as a mystery writer, Alexandria had loyally served as Charlotte’s business manager and typist. After Charlotte’s death, Alexandria described her elder sister as a true lady in the old-fashioned sense, who wore white gloves and large hats and spoke with impeccable grammar. Of the mysteries which Charlotte wrote, Alexandria pronounced that her sister had written them “specifically for people who did not want blood and guts, at least not a whole lot of it anyway. Everybody drank tea and ate molasses cookies. It was that kind of thing.”

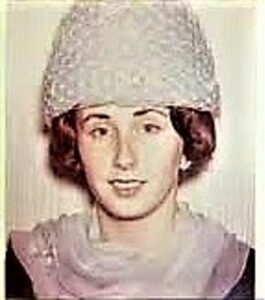

CHIEF OF THE WINTER HILL GANG

Presumably it was not over tea and molasses cookies—it was not that kind of thing—that Lindsey Aldyth (Chester) Cyr, Charlotte’s niece by her other sister, Helen, a secretary at Weymouth High School who died in 1995, made her fateful meeting in 1966 with Whitey Bulger—(who had recently been released from prison—at a Boston cafe where the attractive, hard-working twenty-one year old woman, a part-time legal secretary and occasional model, was covering the breakfast shift as a waitress. For Lindsey—whose Weymouth High School annual described her as “smooth and sophisticated” and “looking forward to a career in fashion design (she “liked sewing and embroidery”)—it was love at first sight with the manly thirty-seven year old mobster, who was, one might say, a real ladykiller (literally). “He was gorgeous,” Lindsey recalled adoringly. “There wasn’t anything not to be attracted to. He was blond, blue-eyed, very well-built and handsome.” The vicious multiple murderer was also, in Lindsey’s eyes, “a perfect gentleman who made her feel safe.” Seemingly there was nothing not to like about the man!

again with the hats Charlotte MacLeod’s niece Lindsey Cyr onetime lover of Whitey Bulger and the mother of Whitey’s son Douglas

again with the hats Charlotte MacLeod’s niece Lindsey Cyr onetime lover of Whitey Bulger and the mother of Whitey’s son Douglas

Lindsey and Whitey quickly launched a romantic relationship, which by the way inadvertently produced a son, Douglas, the next year. However Douglas, a lovable child (blonde-haired, like his Dad), died tragically young at the age of six from Reye’s syndrome in 1973. Whitey attended the funeral of his boy, in the upbringing of whom he had been involved. Lindsey, who was together on-and-off with Whitey for about fifteen years and was sometimes described by newspapers as his “common-law wife” (or even just “wife”)—first spoke out about the relationship in 2010, a year before the fugitive was arrested and imprisoned for what turned out to be the last seven years of his life. A hit film about Bulger, Black Mass, was released in 2015, with Johnny Depp playing Whitey and Dakota Johnson playing Lindsey.

Until her own death in 2019, less than one year after Whitey’s ghastly murder, Lindsey Cyr continued to talk to newspaper and book interviewers about her relationship with the mobster when they came to call, as she did, for example, in 2015 when she pronounced that Black Mass was an “awful” film and a couple of years earlier when she declared incredulously that a documentary about Bulger’s life “made him out to be a demon.” Loyally Lindsey avowed of her imprisoned former lover that she would, just like the Dolly Parton/Whitney Houston song says, always love him.

Lindsey Cyr was hardly alone in having been dazzled by Whitey’s Irish charm. John “Terry” Terranova, Bulger’s longtime South Boston barber (who later moved to Weymouth), recalled warmly of Whitey: “He would tip his hat to women…He’d help people in the projects who were in need. You would like him in a minute. My wife thought that he worked for an insurance company because of the way he was with people.” Myself, never having the great man, I have to wonder: What did Lindsey’s Aunt Charlotte think of her niece’s inappropriate, if not bizarre, love match? About this there may be a few hints in one of her early cozy crime novels, A Pint of Murder.

A PINT OF MURDER AND A PORTRAIT OF LINDSEY?

In 1980 Charlotte MacLeod published, under his Alisa Craig pseudonym, A Pint of Murder, her fourth crime novel and the debut title in her five-book series of her Inspector Madoc Rhys detective novels. Just the previous year the Boston Globe had darkly reported, in a long article about Whitey Bulger’s rising politician brother entitled “Who Is Billy Bulger?”, that “James J. (Whitey) Bulger…has long been linked to the Boston underworld.” However, Charlotte MacLeod, who was writing Pint that same year, set the novel not in Boston but on her parents’ native ground in New Brunswick, Canada, albeit at a fictionalized town named Painterville. (A town named Florenceville is located just ten miles down the St. John River from Charlotte’s birth village, Bath.) Surely MacLeod’s “About the Author” blurb at the back of the book is one of the most elliptical ones in existence, suggesting the cozy crime writer was desirous of maintaining Alisa Craig’s personal anonymity: “Alisa Craig was born in Bath, New Brunswick, and once has a mad crush on Renfrew of the Mounted [the title character in a 1937 Candian Mountie film]. More than that she does not intend to say.” (By 1983, however, she had revealed that Alisa Craig was really Charlotte MacLeod.)

Despite such initial reticence, in the author’s note at the beginning of A Pint of Murder, MacLeod made clear that her novel’s setting was steeped, like relaxing chamomile tea leaves in a pot of warm water, in the New Brunswick of the tales her parents told her: “To a Canadian child growing up in another country, [Canada] was always the place where the stories came from. There were stories told to her by her mother, to whom the St. John Valley was always Home pronounced with a capital letter; stories told to her by her father to whom the Maritimes had been the happy hunting ground of his youth.” Nevertheless, she added, doubtlessly with her publisher’s commercial mind dwelling on the lamentable possibility of lawsuits: “Now that her parents’ bodies are back in the place their spirits never left, she makes up her own stories. This is one of them. Pitcherville and all its inhabitants and doings are straight out of her imagination, therefore any resemblance to actual persons or places would be astonishing as well as unintended.”

Methinks she doth protest too much. To my mind it stretches credibility to think that MacLeod really would have been flabbergasted by any resemblances that might have been pointed out to her of persons and places in the novel to real ones in New Brunswick—or, say, Massachusetts. For example, Janet Wadman, the charming woman protagonist of the novel, has a farmer brother, Bert, to whom she is greatly attached and who, recalling MacLeod’s only brother Walter, is an enthusiastic member of a local masonic lodge, the Order of the Owls. Janet is fifteen years younger than Bert, recalling Charlotte’s own baby sister Alexandria, who was fifteen years younger than she (and seventeen years younger than Walter). At one point characters gather to play cribbage, Walter MacLeod’s favorite game.

Additionally the rustic Marshall in Painterville, Fred Olson—whom the author presents quite sympathetically even if he is clearly in over his head when it comes to multiple murder—shares the name of the rustic Houlton, Maine sheriff Frank Hogan, the man who informally deputized her then fifteen-year-old father Phil way back in 1908. Like Sheriff Hogan, Marshall Olson spends his professional life as a lawman mostly in locking up weekend drunks. Further, when Inspector Rhys Madoc of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrives on the scene nearly midway through the novel to take over the investigation of a pair of apparent murders, the author informs her readers, with deliberate, comical deflation, that Madoc resembles not dreamy Nelson Eddy, the fictional Mountie of the 1936 hit American film Rose Marie, but rather “an unemployed plumber’s helper,” being barely the “minimum five feet, eight inches height” required by the Mounties. I cannot help thinking here of MacLeod’s beloved undersized plumber father, who enjoyed, hobbit-like, so many adventures despite his diminutive stature.

Although Lindsey Cyr’s 2019 Weymouth obituary fails to mention her aunts Charlotte and Alexandria (not to mention her mother Helen and her father, whose identity remains unknown to me), it does mention her Uncle Walter MacLeod as well as her Grandmother Mabel MacLeod. However, Lindsey was one of the co-dedicatees of Charlotte’s book Brass Pounder, suggesting that the two at one time at least had a friendly relationship. In A Pint of Murder, one of the characters, pretty blonde Gilly Bascom, seems to reflect, sympathetically on the whole, certain elements from Lindsey Cyr’s own life. Gilly—the young daughter of hoity-toity Mrs. Elizabeth Drufitt, the wife of the town doctor (such as he is) and doyenne of the Tuesday Club—ran off something like a decade ago with a certain Bob Bascom. He soon dumped her, leaving her alone to raise their “misbegotten son” Bobby. Gilly refuses to move back in with her parents, instead eking out a living on her own in Painterville, waitressing at the local grease pit, The Busy Bee.

Characters repeatedly refer direly to this situation throughout the novel, agreeing on one thing, anyway, that Gilly’s husband Bob Bascom was a thorough bad egg:

“I wouldn’t have wished a kid like [Gilly] even on my cousin Elizabeth. Running off with that Bascom creep even before she got through high school, then crawling back with a brat on her hands after he ditched her. And holing up in that shack beside the diner instead of going home that nice, big house when Elizabeth practically begged her on bended knee. But, no, Gilly had to be independent….Waitressing part-time at the Busy Bee….”

“So the next thing anybody knew she’d run off an’ married that no good Bob Bascom an’ if that ain’t cuttin’ off your nose to spite you face I like to know what is.”

“She was skinny an’ big-eyed then like she is now….Then Gilly ran off with Bob Bascom who wasn’t worth the powder to blow him to hell….”

“[Her mother] wouldn’t stand for Gilly lowerin’ herself an’ the family no more’n what she’d already done, runnin’ off with that Bob Bascom….her mother says…Gilly was no judge of men, which is true enough on the face of it, I guess, though Bob Bascom never had a chance with them so down on ‘im right from the start—not that he was much to start with.”

Poor naïve Gilly: a single mother with a young son to raise and a waitressing gig at a crummy local dive, who foolishly threw herself away on that no-good Bob Bascom. Although we never learn just what was so bad about the enigmatic Bob Bascom (aside from the obvious fact that he walked out on Gilly and Bobby), could Bascom have been any worse a prospect for a nice, if deluded, girl than Whitey Bulger? To make their own assessment of Gilly Bascom, I urge people to read A Pint of Murder. It is a fine detective novel in its own right, whether or not in the end it has any bearing on the strange love ballad of Lindsey and Whitey.