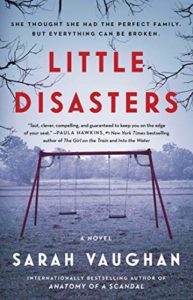

My new novel, Little Disasters, begins with an inconsolable baby screaming at a night and a mother who feels extreme distress at being unable to calm her. The crying, which continues for hours each evening, is relentless and the mother “does not know how much more she can bear.”

If, to quote Nora Ephron, everything is copy, then this mother’s visceral sense of helplessness was inspired by my own experience with my firstborn, a baby who was gripped with colic from three to sixteen weeks and who seemed to scream with inexhaustible fury. As a 32-year-old, who, bar a failed driving test and some infertility treatment, had largely succeeded at things, I found this baffling, shaming, and terrifying. Of course, the colic stopped, and by about 18 months, my baby slept. But the sense of profound incompetence—why couldn’t I get her to sleep? Why did she hate me so much?—and the speed with which my sense of self started to unravel stayed with me a lot longer. In those days, I was a news reporter, not a novelist, but perhaps even then I was aware that the situation was rich with narrative potential.

Because motherhood is an area that’s ripe to be explored in psychological suspense and crime fiction. After all, it begins with blood, pain and terror—before ricocheting violently from joy to panic, self-doubt, and an exhaustion so extreme that, in the case of Jess, one of the mothers in Little Disasters, she imagines tipping her baby down the stairs. After my second child was born, a perfect storm of circumstances—a difficult pregnancy resulting in chronic pain; moving miles away from my support network; giving up the career that had defined me—meant I spiralled into postnatal anxiety and excessive catastrophising. It didn’t take too great a leap of imagination to put myself in the head of a mother plagued by intrusive thoughts, her inner critical voice growing ever more clamorous. Who needs a protagonist whose judgement is skewed by drink, or a gaslighting husband, if she can bring this on herself simply by having a baby?

Motherhood is an area that’s ripe to be explored in psychological suspense and crime fiction. After all, it begins with blood, pain and terror.Of course, writers have always been fascinated with bad mothers, and have been particularly judgmental if sex is thrown in. (Think Medea, who kills her own children to enact revenge on her murderous husband, Gertrude in Hamlet, despised by her son for marrying her brother-in-law, and Emma Bovary.) Maternal negligence and thoughtlessness are derided—remember Jane Austen’s sly satire of Mrs Bennett about whom she’s far less critical than apathetic Mr Bennett?—but fiction has often veered away from exploring maternal ambivalence. (Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, a reimagining of Hamlet and Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk about Kevin are easily conjured exceptions.)

Recently, however, there seems to have been a shift. TV dramas, such as Big Little Lies and Little Fires Everywhere, have explored not just the frustration of the stay-at-home mum but, more dramatically, maternal domestic abuse and postnatal depression, (both, interestingly, additions to the mini-series from the novels). Meanwhile, a slew of non-fiction—Clover Stroud’s My Wild and Sleepless Nights, Nell Frizzell’s forthcoming The Panic Years, Catherine Cho’s Inferno, about her postpartum psychosis—have depicted versions of motherhood a world away from the cutesy cosiness of Annabel Karmel, or the soft filtering of an Instagram page.

If memoirs are exposing the rollercoaster of early parenting, fiction—as ever—can think bigger and go one step further. As Phoebe Morgan, editorial director of HarperFiction at Harper Collins, and the author of psychological suspense The Babysitter, says. “There is some excellent non-fiction about motherhood, but fiction is the area that really pushes the boundaries as far as they can go because you can be honest in fiction and it will never be held against you. After all, it’s not you: it’s the characters.”

Nowhere is this willingness to be brutally honest clearer than in psychological suspense, which often probes the darkest reaches of our psyches and delights in tackling taboo subjects. Having done the toxic husband-wife dynamic to death, perhaps the parent-child/ mother-baby dynamic was the next obvious relationship to be examined. After all, if we’re not a parent, then we’ve all been someone’s child.

“It’s a relatively universal relationship—which is ultimately why readers can relate to it,” says Morgan. “If you don’t have children, you probably know people who do, so it’s easy for a reader to put themselves, or someone they know, in the driving seat of a parent/child narrative.” So intense is the enthusiasm for this sub-genre that UK publishers—who always loves a label—have dubbed it “mum-noir.”

Indeed, motherhood is such a fertile area for exploration that psychological suspense mines it in at least four, sometimes overlapping ways: by depicting a monstrous mother; by resting on a typically problematic surrogate—a nanny, or a stepmother; by exploring swiftly formed and unnaturally intense maternal friendship groups; and, to my mind the most compelling, by interrogating the disordered thinking, and fractured sense of self; the claustrophobia and isolation, that can accompany those early years.

If Ali Land’s serial killer mother in Good Me, Bad Me is the most extreme example of monstrous motherhood, then Gillian Flynn’s Adora, in Sharp Objects, runs a close second. But it’s international bestseller Liz Nugent who has made toxic mothers her speciality. While Lydia in Lying in Wait is a “smother” (a “smothering mother” who can claim “I made him and he is mine”), the mothers in Skin Deep and Little Cruelties reject their children and effectively destroy them through their narcissistic behavior.

“They say the home’s the most dangerous place,” says Nugent. “I always think: why not make it the most unlikely person the most dangerous: the mother? I like to go psychologically really dark.”

One of nine children, Nugent chose not to become a mother herself: a decision that means her friends are more willing to be open about their own maternal ambivalence. “I think it’s one of the last taboos: one of those things that just isn’t talked about. I have friends who have admitted they don’t like their children. Not that they don’t love them but that they don’t like them, and some have admitted that they regret having them; that, had they not felt pressured by societal norms, they wouldn’t have done so. They feel pressure from their family and circle of friends—and then they feel estranged from their friends who adore their own kids.”

In a society where the decision not to have children is still an issue, this all this makes for unsettling fiction.

If Nugent’s mothers are viciously toxic—Melissa’s blame game in Little Cruelties is devastating; Delia’s continued rejection of her son, in Skin Deep, brutal—then the mothers who absent themselves to allow a replacement mother to take their place, are more subtly problematic. Sometimes, the plot demands this, as in Ruth Ware’s Henry James-inspired The Turn of the Key, where the mother is only too happy to leave her children in the care of their new nanny for two weeks the morning after they meet. But where the mother hangs around, the reader, perhaps validating their own childcare choices, becomes judgmental. In Gilly Macmillan’s The Nanny, newly bereaved Jo, who has a difficult relationship with her own mother, appears increasingly foolhardy in putting her own daughter in the care of her old nanny, Hannah, while in Leila Slimani’s The Perfect Nanny, barrister Myriam, frustrated and terrified by motherhood, too swiftly views nanny Louise as an indispensable “miracle worker”. There is a particularly damning passage in which Myriam, plagued by anxieties about her own childhood, absents herself from her daughter Mila’s birthday celebration by hiding in the bedroom “pretending to answer emails” while Louise plays with the children. By focussing on Myriam, who works long hours and has an affair, and not husband Paul, whose career has been unimpeded by their children, it’s hard not to perceive a touch of misogyny.

If the toxic outsider who infiltrates the family is a threat then frenemies—forged through swiftly-formed friendship groups at the school gate, or in the intense, anxietycharged atmosphere of a prenatal class—are another feature of “mum-noir” thrillers. In Harriet Tyce’s The Lies You Told, single parent Sadie grabs the childcare offered by two mothers in her new friendship group with gratitude and near fatal consequences; while in Jane Shemilt’s The Playground, bohemian, dysfunctional Eve, desperate for her children to have an unfettered, carefree childhood, embraces other families and children, and is woefully negligent.

Antenatal groups feature in Caroline Corocan’s The Baby Group, and Katherine Faulkner’s Greenwich Park, out in 2021, while in my own Little Disasters, the friendships forged at a prenatal group persist a decade later, leading to clashes of personalities and persistent doubts and tensions. As with Big Little Lies, the opportunities for these very different mothers to meet, at a nativity, book club, sports day, summer fete—and yes, at the school gate, mean they are repeatedly thrown together as the dynamics shift and darken. As Liz, a pediatrician, notes of the least likable mother in their group: “Charlotte’s Charlotte.” She would never have been a natural friend had we not met while we were all going through the same, life-changing experience, but that shared history…means we can’t just drop her.”

Of course, if friendships provoke feelings of competitiveness and inadequacy, social media is also a factor. But I’d argue that modern motherhood with its emphasis on perfection itself engenders this self-doubt.

There are sociological reasons for such maternal perfectionism, not least the rise of the nuclear family and the tendency to move away from familial support systems, meaning new mothers no longer receive as much practical support or reassurance as in previous generations. “We are responsible, alone, pretty much for creating perfect children, and that’s to our disadvantage,” says clinical psychologist and author Linda Blair.

With no one to regularly check in with, disordered thinking can become the norm and a sense of isolation acute: common features in these early motherhood psychological suspense novels. Stephanie, a mother of colicky twins in Shari Lapena’s The End of Her, for instance, is an only child who has lost both her parents; Mariah, the struggling stepmother in Lucy Atkin’s Magpie Lane is estranged from her mother and trapped in the disapproving milieu of an Oxford college; Margot in Harriet Walker’s The New Girl succumbs to paranoia while on maternity leave; while in Little Disasters, Jess is the only one of her friends to remain at home with a baby, while Janet lives in rural Devon “down steep-banked lanes”.

In Ashley Audrain’s forthcoming The Push, Blythe, deserted as a child by her own mother, feels isolated as soon as she gives birth to Violet. “I felt like the only mother in the world.. who couldn’t pretend to function with her brain in the vise of sleeplessness. The only mother who looked down at her daughter and thought, Please. Go away.”

The sensation becomes even more acute when she attends baby groups.

“Sometimes, I’d find the courage to say what was really on my mind. I’d throw it out like bait: “This is pretty hard some days, isn’t it? This whole motherhood thing.”

“Sometimes. Yeah. But it’s the most rewarding thing we’ll ever do, you know? It’s all so worth it when you see their little faces in the morning.” I studied these women closely, trying to find their lies. They never cracked. They never slipped.”

The isolation is often compounded because the husbands in these thrillers don’t understand the psychological torment endured by their spouses: after all, their sleep’s preserved and they get to leave the claustrophobic domestic setting all day. When Blythe tells her husband, Fox, that Violet hates her, he responds: “It’s all in your head.” (It’s not coincidental that Nikki Smith’s thriller about the darkest reaches of motherhood is entitled All In Her Head.)

Later, when she fears Violet may harm her baby brother, Sam, Fox tells her: “You’re probably making something out of nothing. Again.”” Crucially, Blythe, who narrates the whole book as a confession written for her ex-husband, continues: “But here’s what you didn’t understand: There weren’t many places where my mind wouldn’t go. My imagination could tiptoe slowly into the unthinkable before I realised where I was headed…”

Blythe’s catastrophizing is deliberate—“The thoughts I had were awful, they were harrowing... Enough. I’d snap back”—but for my character Jess such thinking is unavoidable. She becomes consumed by the alternative narrative she envisages, seeing herself dropping her baby or scalding her with a tumbling kettle. “She starts] to see danger everywhere.”

As with mothers who develop intrusive thoughts in real life, Jess’s disordered thinking is sparked by a traumatic birth that fails to live up to her impossibly high expectations. (She imagines an idyllic home birth with Mozart playing and lavender-centred candles.) In The End of Her, Lapena similarly lays bare the connections between perfectionism, birth trauma and loss of self.

“Stephanie had always been a little bit of a control freak, and she’d spent a lot of time wanting everything to go just right,” she writes. “Once they were in the labour suite, though, the plan soon went out the window… It was hard not to feel like a failure in those early days, struggling with sleeplessness, the pain of the C-section recovery, and the frustration of breastfeeding two babies, seemingly all the time….”

As Lapena suggests, exhaustion only compounds the problem—something Celia Freeman understood back in her 1958 mystery The Hours Before Dawn, which begins with the heartfelt—and brilliantly relatable—line: “I’d give anything—anything—for a night’s sleep.”

In fact Stephanie, who begins to fear her husband’s a murderer, even googles sleep deprivation and notes: “There can be the physical effects…But it is the psychological effects that are even more concerning. Forgetfulness. Yes. Emotional instability. Mood swings. Yes, but it’s hard to tell if they’re from loss of sleep considering the circumstances.”

Exhaustion makes for irrational thinking, explains Blair. “As soon as you are tired, emotions dominate. If you have slept, you can believe you’re a better mother or a perfect father; if you’re exhausted, your kid is either wonderful or just disgusting. You need sleep to allow for the middle shades of possibility.”

Exhaustion can also lead to the “perfectly normal fantasy” of “wishing the source of the exhaustion away.” “When you’re sleep deprived, you want to eliminate the cause of the problem. It’s completely normal…to turn to the source of that exhaustion and wish it away. Of course, you don’t act on it, but the thought is a kind of release.”

Except that, in psychological suspense you might act on it, or at least you might fear that you might. Sleep-deprived, isolated, misjudging themselves and their relationships, these mothers can find it hard to navigate the boundaries between truth and lies; between reality and their deepest fears.

It all makes for compelling suspense, as the reader is misdirected while being exposed to an honest exploration of the extreme difficulties of early motherhood.

As Jess notes, in Little Disasters, “there is little more lonely than being at home with a screaming baby and a mind that’s unravelling.”

And perhaps, in a world where the picturesque posts of a mommy blogger are still an aspiration, this harsh reality check is very much needed.

***