― “I tried to find my own edges again, tried to remember the shape of my own body, repeating the same words out loud as I tried to keep myself from disappearing―I belong to no one.”

When I first set out to write a piece of fiction that explored some of the murkier depths of consent and personal agency, I knew the first treacherous step would be to untangle my own story from the one I was building in my head. I knew, though, that no matter how aware I stayed of the sixteen-year-old version of myself that still moves through the rooms of my memory, she would end up on the page. Her pain, her fear, her complete lack of understanding of what had been done to her and just how little she deserved it.

At sixteen, I had no idea there was any difference between seduction and manipulation. I’d read books and watched TV shows and movies where young people pushed and pressured until the other gave in, until they uttered that “yes” I was certain was all anyone needed for sex to be consensual. The stories I read about sexual assault and rape all felt very straight forward―someone said no, and they were not listened to. Someone was incapacitated and taken advantage of without their knowledge. Someone was violently assaulted by a stranger, an acquaintance they had no real emotional bond to. I never really found myself reading stories that featured characters navigating the tumultuous, troubling space of being assaulted by someone they already loved, someone they cared for, someone they may have even said yes to and been intimate with before. That’s not to say these stories didn’t exist, they just weren’t the ones I saw enough to really notice or to critically examine and identify how I fit my own ideas of consent into them.

Today, I work as a trained confidential advocate for victims and survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault. I spend my work hours talking with young people and adults alike about healthy and unhealthy relationships, the red flags of abusive behaviors, and what to do when you see them happening. I speak and work with victims and survivors at various points in their journeys―from the raw, fresh hurt of a hospital visit after an assault, all the way to folks seeking help years down the road, when the weight of it becomes too heavy to keep carrying alone. I have heard stories from survivors who, even years later, still struggle with finding the language to name what happened to them.

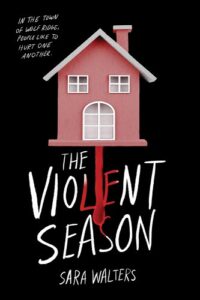

When I set out to write this part of my new novel The Violent Season, it was part of a larger exploration of what drives people to hurt others, and themselves. I wanted to represent one of those nuanced, murky, difficult circumstances where sometimes a victim may not recognize themselves as having been victimized to begin with because the violence took place at the hand of someone they loved and trusted. In The Violent Season, the narrator is seventeen-year-old Wyatt, a girl whose every heart string is wrapped tightly around Cash, the boy she has loved since the start of high school. Cash is Wyatt’s best friend, their bond forged through shared trauma and a twin longing to see their own pain reflected in someone else, that single hand extended into the dark. Cash, set on leaving their small, suffocating town of Wolf Ridge, refuses to anchor himself to Wyatt in the way she wants him to, but continues to string her along, thriving on her unending need for him. Through Wyatt’s voice, we learn that her relationship with Cash is an intimate one, but often only when one or both of them is intoxicated, or when she is begging for that closeness. She becomes so accustomed to his coldness that even the smallest show of tenderness earns Cash another level of devotion from her―the kind of hot and cold manipulation so often used by abusers to keep victims in a lurch, to keep them believing that the good moments still outweigh the bad.

Wyatt’s assault is not a unique scenario―this story plays out so often in the lives of very real young people and adults, and just as often, those victims may not fully understand what happened to them, and may or may not even have the language to label it as assault. Working with survivors, I have heard the same unfortunate refrain so often: I did this, I set myself up for this, I told them yes before, I said yes at the beginning, I didn’t know I could say no later. The heaviness of guilt is palpable with survivors of sexual violence; guilt at not responding how they wished they would have, guilt for accepting or rejecting their abuser’s remorse or apology, guilt over standing up for themselves and not standing up for themselves enough.

So, why write about consent in a young adult novel? Why explore the nuances of love and intimacy in a narrative starring and meant for young people? For me, the answer is simple: pandering to young people isn’t the way to reach them. We have to recognize that young adults and teenagers are emotionally complex and able to unpack and understand difficult and heavy things. We need to make space to explore the very real experiences and emotions so many young adults actually have.

We learn as advocates that one of the most important things we can do for a victim or survivor is to validate them and their experience, to remind them that they aren’t alone, they did not deserve what happened to them, and their emotions and responses are valid and normal. By exploring narratives of nuanced and authentic experiences with things like consent, personal agency, and accountability, we can offer the space for readers of all ages to better understand their own ideas and understandings about each of these concepts. If we start the conversation about these concepts earlier, we might have a chance at stopping violence before it happens, with education and empowerment.

***