Television history may not recall the second week of September 1974 as indelibly momentous. Yet for fans of small-screen private eye series, it most certainly was. On Friday, September 13, NBC-TV’s The Rockford Files premiered, featuring James Garner. That was just one night after competitor ABC launched another Southern California-set gumshoe drama with a well-known lead and lofty ambitions: David Janssen’s Harry O.

The former program went on to five and a half seasons of public acclaim (plus eight TV reunion movies), and in 2002 was ranked No. 39 on TV Guide’s list of the “50 Best Shows of All Time.” While a previous Janssen crime series, The Fugitive, scored even better than Rockford in TV Guide’s poll—seizing the No. 36 spot—Harry O was nowhere among those 50 picks. Despite the fact that it consistently won its time slot, was nominated for an Edgar Award, and earned one of its performers an Emmy, Harry O was axed after only two seasons. It’s said that Janssen was so embittered by that cancellation, he swore off ever tackling another weekly production.

Preliminary judgments of Harry O were decidedly mixed, but in the 45 years since that show’s concluding episode aired, its reputation has been burnished by retrospective reassessment and patent nostalgia. Writing in The New York Times in 1977, David Thorburn, a literature professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, opined that Janssen’s eponymous sleuth, Harry Orwell—with his twisted smile, tweed sports coat and khaki pants, and contemplative nature—was “more credibly and richly imagined than nearly all the TV detectives who preceded him, a true successor of the private eyes in the novels of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler and in the movies that grew out of those books….Harry O drew creatively on this popular mythology, and the pleasure of watching the show partly consisted in one’s repeated recognition of the variations and shadings the series introduced into this fertile American tradition.” Meanwhile, Allen Glover noted in TV Noir: Dark Drama on the Small Screen (2019) how thoroughly Janssen threw himself into his Orwell role, remarking that he “laid the bone-weary but persevering tally of his own life right on the counter, like a bar tab covered with too many cigarette burns and glass rings.”

“When Harry O first appeared in 1973,” says Robert J. Randisi, the author of several detective-fiction lines and founder of the Private Eye Writers of America, “it immediately became my favorite private eye television show. Also my favorite dramatic show ever. David Janssen, as Harry Orwell, embodied the perfect private eye….As much as I liked the more successful Rockford Files, I still preferred Harry O’s more serious tone, and Harry’s loner persona….The only other [show] I find comparable in the slightest is Darren McGavin’s The Outsider.”

“No actor on television,” the late critic Michael D. Shonk asserted in Mystery*File, “has been more convincing as a P.I. than David Janssen.”

Considering plaudits of this caliber, it’s astounding and regrettable to boot that Janssen’s final TV vehicle is today largely forgotten.

I was a school kid during Harry O’s prime-time run, and its weekly installments commenced past my bedtime. So I didn’t catch up with the series until decades later. That it was waiting around for me to enjoy—that it existed at all!—owed a great deal to the audacity of its creator, the appeal of its headliner, and not a little good luck.

* * *

If not for prolific, award-winning screenwriter Howard Rodman, the early 1970s might have seen two TV crime dramas inspired by Clint Eastwood pictures, rather than just one. The first such program, of course, was Dennis Weaver’s NBC Mystery Movie series, McCloud, which borrowed its “cowboy in a big city” premise from Eastwood’s 1968 film, Coogan’s Bluff. Then in 1972, a couple of years after McCloud’s start, Warner Bros. began exploring the possibility that its big-screen action-thriller Dirty Harry (1971), which had introduced Eastwood as San Francisco cop “Dirty” Harry Callahan, could become the basis for a boob-tube hit.

The studio took this idea to Rodman, who’d devised scripts for shows such as Naked City, Route 66, and The Man from U.N.C.L.E., and had co-written both Coogan’s Bluff and—under the pseudonym Henri Simoun—Richard Widmark’s 1968 hard-boiled cop sensation, Madigan. But Rodman was plainly unimpressed, for he came back to Warners with an entirely different proposal: an hour-long weekly serial pivoting around a private investigator in the Philip Marlowe/Sam Spade/Lew Archer mold, a veteran solo operator whose hard-knocks-won cynicism vies constantly with his hopes for a better life—for himself as well as others. Originally named Frank Train, Rodman’s principal was to be an aging, fallible, often brutally honest ex-policeman who lives on a disability pension he earned through the misfortune of being shot in the line of duty, and moonlights as a shamus. He has a modest house on the beach, along with a battered old sailboat—The Answer—that he’s striving to make seaworthy once more. He doesn’t boast many friends, but will race out on a limb to help those he has, while simultaneously denying any altruistic motives. In addition, he refuses to carry a gun, and he doesn’t drive; instead, he gets around via public buses.

Rodman’s P.I. could hardly have had less in common with Warners’ Dirty Harry expectations. Even so, the studio agreed to proceed with a Harry O pilot.

That meant enlisting a star. Believe it or not, Telly Savalas was one of the actors considered to play Orwell. However, he had to pass (thank goodness) after accepting the main role in The Marcus-Nelson Murders, a gritty 1973 CBS flick that spawned the New York cop series Kojak. Rodman and his pilot’s director/producer, Jerry Thorpe (The Untouchables, Kung Fu), turned alternatively to David Janssen.

A Nebraska native, born David Harold Meyer in 1931, Harry O’s eventual leading man had moved with his divorced mother (a onetime Ziegfeld Follies showgirl) to Los Angeles when he was 5. He reportedly excelled at basketball and track-and-field sports as a youth, and dreamed of an athletic career, but a high school pole-vaulting accident inflicted him with lifelong knee problems and refocused his future on acting. By age 25, jug-eared and dimpled David had shot 20 mostly forgettable films. Then in 1957, Janssen—as he’d restyled himself for Hollywood, taking the last name of his mother’s second husband—landed the title part in Richard Diamond, Private Detective, a half-hour CBS (later NBC) series based on a Dick Powell radio mystery of the same name. That led him into a brace of TV ventures, ABC’s The Fugitive (1963–1967) and CBS’s far-less-welcomed Jack Webb presentation, O’Hara, United States Treasury (1971–1972).

Janssen could be aloof in person, but he was charismatic on screen. He had a rep, too, as a workhorse, someone who rarely took breaks from performing and whose talents had gained him hordes of devotees. The Los Angeles Times once called him “television’s quintessential actor.” Regardless of all that, it took time for Thorpe to envision Janssen as Harry Orwell. “I thought he was too elegant,” Thorpe confided to Ed Robertson of Television Chronicles magazine in 1997. “He had a kind of ‘movie star’ quality, like a Clark Gable, which I didn’t think would work for this particular character. Clearly, I was wrong. And I soon became a very big David Janssen fan.”

* * *

In the initial pilot, Martin Sheen (left) played the guy who’d ended Harry Orwell’s police career—with a bullet.

In the initial pilot, Martin Sheen (left) played the guy who’d ended Harry Orwell’s police career—with a bullet.

What’s easily overlooked is that Harry O was almost a failure from the get-go. The pilot Rodman and Thorpe had persuaded Warner Bros. to back debuted on ABC-TV on March 11, 1973. It was shot to fill a 90-minute “movie of the week”-style hole, but the network insisted on cramming it into a 60-minute slot as part one of a Sunday-night “double feature” that presented, afterward, the pilot film Intertect, starring Janssen’s old pal Stuart Whitman (Cimarron Strip) as a jet-setting former spy who currently heads up an international detective agency called Intertect (which, coincidentally, was also the name of the high-tech security firm that employed Joe Mannix in Season 1 of Mannix). Rodman and Thorpe agreed to trim their teleflick, but that did it no favors, as critics complained about narrative gaps attributable to the truncated running time.

Those weren’t the only strikes against Harry Orwell’s TV premiere.

The pilot’s plot was quite promising: Harlan Garrison (played by Martin Sheen), a Vietnam vet who, four years prior, had shot Orwell during a drugstore burglary that resulted as well in the death of Harry’s partner, offers to give the P.I. $1,400—enough to pay for surgery to remove the bullet lodged near his spine. In exchange, Garrison wants Orwell to track down Walter Scheerer (Sal Mineo), the guy who’d joined him on that break-in. Garrison is certain that Scheerer, who has already purloined his junkie girlfriend, now wants to snuff him to keep his complicity in the heist a secret.

Trouble was, Harry was a dick. And I don’t intend that as a synonym for “detective.” Janssen portrayed Orwell as cantankerous and unsociable, a competent crime-solver but personally abrasive. He was especially rude to and dismissive of women, who, nonetheless, were enthralled by him in a cheesy fashion all too common on mid- to late-20th-century television.

Appraising the 1973 pilot, Daily Variety averred that “Janssen’s semi-sullen interpretation of the lead did not look too much like a character viewers could grow fond of.” ABC execs obviously concurred, because they swung thumbs down on Harry O joining their fall 1973 prime-time schedule. (The full 90-minute picture—including a lengthy motorcycle chase terminating in the Los Angeles River—was only later syndicated as Harry O: Such Dust as Dreams Are Made On.)

This wasn’t the first Janssen pilot not to generate a series. In 1960, on the heels of Richard Diamond, he was cast as a rugged Tinseltown press agent in The Insider, a 60-minute Screen Gems production in which he provided succor to a female recording artist (Polly Bergen) who was eager to elude the parlous attentions of a gangster syndicate and make her way on the nightclub circuit. Although The Insider was unable to find a network home—and notwithstanding its short runtime—the film was released in theaters two years later as Belle Sommers. Janssen didn’t get another chance at inducing broadcasters to pick up The Insider. Nor did he expect one.

But Harry O was, well, special. That was due chiefly to Janssen’s favorability. After four seasons of playing a slick Sherlock in Diamond, another four in the meatier role of The Fugitive’s Richard Kimble, a physician who flees for his life after being wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder, and a single year as Jim O’Hara, a Nebraska county sheriff turned uptight federal agent in O’Hara, United States Treasury, Janssen rated high with couch potatoes. Robertson wrote in Television Chronicles that members of a test audience assembled to preview the initial Harry O pilot weren’t wild about Janssen’s protagonist, but liked seeing the actor back on the small screen. They just wanted him to be “firm and capable, with a good amount of toughness, but, underneath, sensitive, understanding and a ‘bleeder’ for the problems of others—qualities that make him vulnerable on several levels.” As Robertson observed, those were the same attributes that had brought his Kimble a loyal following.

When, against the odds, ABC invited Rodman to put together a second pilot, he determined to make clear that Harry Orwell was—to quote Janssen himself—“a part-time investigator and a full-time human being.”

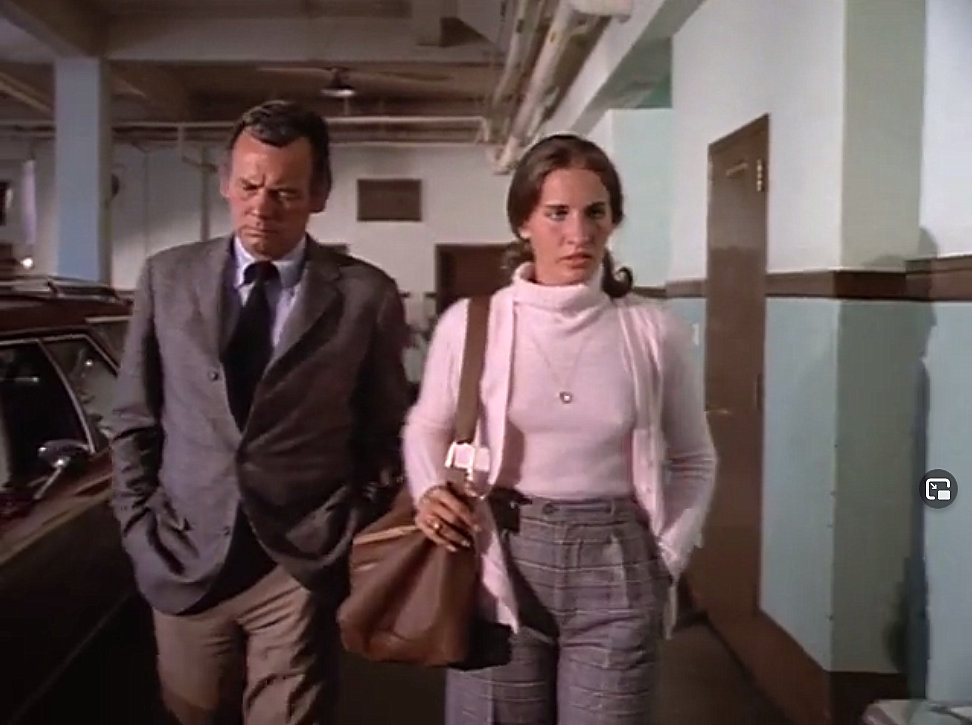

Andrea Marcovicci (right) was the obsession of a homicidal photographer in Smile Jenny, You’re Dead.

Andrea Marcovicci (right) was the obsession of a homicidal photographer in Smile Jenny, You’re Dead.

Smile Jenny, You’re Dead aired on February 3, 1974. That two-hour psychological thriller promoted Orwell as “tough, tender, smart, romantic, experienced and explosive.” The story sees him being implored by an old cop friend to help his daughter, mid-20s model Jennifer English (singer/actress Andrea Marcovicci), who has acquired a stalker: a delusional photographer (future Red Shoe Diaries director Zalman King) willing to slay her estranged husband, her current, elder lover, and any other rivals for her affection. Harry goes about protecting Jennifer, but in the process the 43-year-old gumshoe becomes enamored of the emotionally frangible brunette beauty as well. In a parallel plotline, our hero seeks to aid an adolescent girl (Jodie Foster), who’s been left homeless by her mother’s shoplifting arrest.

Reviewers applauded the movie’s pacing, its intriguingly offbeat camera angles, and its convincing suspense. What really drew and maintained the watcher’s attention, though, was the slow-boiling relationship between Orwell and Jennifer. Fictional P.I.s were always losing their hearts to winsome women on late-20th-century series…and generally bouncing back by the next week’s episode. Yet the poignancy of Harry’s attraction to his protectee, her quiet recognition and acceptance of it, and the inevitability of Jennifer eventually walking away from him were uncommonly well-handled during those couple of hours. In voice-over narration for the final scene, Harry mourned the reality of his aging and the likelihood that he’d never find lasting love:

“Days happen to you. And sometimes I wish I could go back to being 17 again. When I was 17, I once said, ‘A woman is like a bus—let her go, there’ll be another one along in five minutes.’ Now, that was a long time ago.

“Goodbye, Jennifer.”

The Harry Orwell of Smile Jenny was just as shrewd and resolute as he’d been in the preceding pilot, but he was also compassionate, self-effacing, somewhat sentimental, and respectful of the opposite sex. He rather resembled Tom Valens, the part Janssen played in the 1967 film Warning Shot, a strained, sympathetic L.A. police sergeant who—after confronting a suspicious figure he sees wielding a pistol—fires in self-defense…only to be suspended and charged with manslaughter after the deceased’s alleged weapon vanishes from the crime scene. Desperate, Valens turns ad-hoc private eye and embarks on a principally existential quest to demonstrate his own innocence.

Jerry Thorpe told Television Chronicles that he’d learned a great deal about Orwell, and about Janssen, from the first pilot, and sought to bring out more of the performer’s personality in the second go-round. The retooling succeeded: ABC announced Harry O’s addition to its fall 1974 weeknight lineup.

* * *

Crime and detective shows were much in evidence that September. Proven favorites such as Cannon, Barnaby Jones, Ironside, and Columbo were joined by Nakia, Get Christie Love!, The Manhunter, The Rockford Files, and—on Thursdays at 10 p.m., with The Streets of San Francisco as its strong lead-in—Harry O. It was up to Janssen, Rodman, and Thorpe to prove their fledgling drama could stand out from the crowd.

Might it benefit from a change of locale? Harry O’s two pilots had been set in Los Angeles, but ABC suggested basing the series somewhere less orthodox, say, Honolulu or Seattle. The former was a nonstarter, because Hawaii’s capital already hosted Hawaii Five-O, then beginning its seventh season. And what of Seattle? In spite of Washington’s largest burg claiming a long history of literary sleuths, its capricious weather made shooting delays a prospective problem. Thorpe ultimately proposed San Diego, 120 miles south of L.A.—very near the U.S./Mexico border (though Harry O’s stories never exploited that cultural proximity in any meaningful way); he had made a tailored-for-TV flick there a few years before. Filming in San Diego was destined to cost more, but hopes were that Harry O’s success would mitigate such losses.

The show did, indeed, have a lot going for it: melancholy theme music by Billy Goldenberg, who’d composed a dissimilar, haunting score for Smile Jenny (on top of themes for Banacek, Kojak, and the western Alias Smith and Jones); plus prominent directors—Richard Lang, Russ Mayberry, Paul Wendkos, and their like. In Harry O’s maiden season alone, guest stars ranged from Stefanie Powers, Broderick Crawford, Sharon Farrell, and Peter Gunn’s Craig Stevens to Jim Backus, Joanna Pettet, Kurt Russell, James McEachin, The Brady Bunch’s Maureen McCormick (cast against type as a drug addict), and legendary jazz singer Cab Calloway. Then there were Janssen’s rusty-throated voice-overs—reminiscent of those in 1940s radio detective serials—which supplied self-deprecating humor, pathos, and sporadic poetry. (“She hung on to me as if I was the edge of a cliff,” he tells us whilst comforting a sudden widow. “Then a doctor got there and she let go and started falling.”)

Furthermore, at a time when TV detectives vied for quirks, Harold Orwell possessed them aplenty. There was the whole business of his bad back, which led him to stretch and groan (“something that comes to me naturally,” Janssen joked to an interviewer), and sent him running a mile each morning from his beach shack in Coronado, just across San Diego Bay from downtown—an abode set designers had built with hinged walls, which could be opened to facilitate interior shooting. Howard Rodman’s intent in depriving Orwell of an automobile was to avoid any possibility of segments being padded out with rubber-squealing car chases, which he hated. But the show’s writers realized they could have fun, too, with Harry’s mass-transit savvy. During one early story, for instance, the peeper shakes off a tail by exiting the bus he’s riding, thus forcing an intelligence agent shadowing him in a sedan to pursue instead on foot. Orwell then reboards that same coach at the next stop, getting away before the agent can retrieve his wheels.

In what Robertson construes as a concession to the network (“ABC didn’t want to lose out on having the General Motors Corporation as a sponsor”), the P.I. was given a car when the series debuted. However, it wasn’t as cool as either Rockford’s Pontiac Firebird or the DeSoto Fireflite convertible—complete with mobile phone connecting him to a shapely but never fully revealed answering-service operator, Sam (Mary Tyler Moore)—that Janssen piloted as Richard Diamond. Orwell’s ride was a wheezy, gray 1960s Austin-Healey Sprite that was ever in need of repair, and even broke down once as he was being trailed by two hit men. Harry was unwittingly forced to ask those killers for a push off the busy street!

As this show evolved, we learned that Orwell was reared as an only child in Philadelphia, but relocated to California after serving in the Korean War. He spent 20 years on the San Diego police force, and had become a lieutenant prior to catching that bullet. He now bills $100 a day, plus expenses—half of Jim Rockford’s going rate—for his snooping, but occasionally does jobs “on the house” for clients he believes in. He’s divorced, despises telephones but gets along with young people, operates out of his home (which is frequently the target of criminal attack), and harbors few ambitions. “There was a time when I thought I wanted to be the chief of police,” he confesses, but in the long run settled for “just being a guy that goes to work and tries to make a living, keeps his promises, and gets a kick out of walking on the beach, looking at the sunset.”

Oh, one other thing: the P.I.’s repairs to The Answer would never end. Before Harry O started, Janssen told Francis Murphy, TV columnist for the Portland Oregonian, that the series offered unlimited story possibilities: “[Orwell] can get the boat built and set off on a cruise to the islands. Or we could have a couple of love stories with no crimes involved.” Neither ever happened, and the first one was impossible, because as Rodman told author Ric Meyers for the 1989 book Murder on the Air, Harry’s boat was a metaphor for the answers he wants from life, “which never come to reality.”

* * *

Forty-four weekly installments of Harry O were shot over two seasons. Like other critics, Ed Robertson (today the host of TV Confidential, a syndicated radio talk show about television history) ranks the primary 13—those set in San Diego—as the most singular and memorable. “They were, by design, written more like a novel than a typical 60-minute episodic private eye drama,” he explains. “This is particularly true of the first act of each of those first few shows. The premise unfolded at a leisurely pace (more like an HBO pace, so to speak); we got to know a little bit more of Harry’s existential character and bohemian personality each week, while the guest characters he met from week to week were also pretty well developed. That was unusual for network TV in 1974.”

Henry Darrow (right) portrayed Orwell’s San Diego police contact, Lieutenant Manny Quinlan.

Henry Darrow (right) portrayed Orwell’s San Diego police contact, Lieutenant Manny Quinlan.

Those atmospheric San Diego episodes found Henry Darrow, who’d filled the dusty boots of Manolito Montoya on the 1967–1971 western, The High Chaparral, playing snappy-dressing Lieutenant Manuel “Manny” Quinlan, Orwell’s friend and reluctant police ally. Stories varied in tenor, but were routinely thought-provoking and profuse with human tensions, addressing the damage life can inflict upon certain individuals. An anomaly was the witty inaugural tale, “Gertrude,” which had Orwell joining Gertrude Blainey (Julie Sommars), a ditzy moralizing blonde, in the search for her sibling, Harold (Les Lannom), who’s gone AWOL from the Navy. Her single clue to his whereabouts? A brand-new civilian left shoe he’d mailed her way. Replete with lively badinage between Orwell and his client, as well as dexterously crafted puzzle elements, “Gertrude” was tipped to win scripter Howard Rodman the 1975 Edgar Award for Best Television Episode from the Mystery Writers of America, but it lost out ultimately to a teleplay for the anthology series Police Story.

Truer to form was “Guardian at the Gates,” centering on a prominent—and arrogant—architect, Paul Sawyer (Barry Sullivan), whose life has been threatened. Harry’s willingness to help clashes with his loathing of Sawyer, whose scattershot abuse doesn’t even spare his daughter, Marian (Linda Evans), with whom the shamus strikes up a tentative romance. As Mystery*File’s Shonk wrote, “The story is less a mystery than an examination of a genius without humanity, the price of such genius and the suffering it causes others around him.” Noteworthy besides was “Eyewitness,” one of several episodes rooted in Southern California’s Black communities. It sends Orwell in support of the nurse who’d led his recovery after he was shot. Her son has been arrested for homicide, but the teenager professes his innocence. Harry’s probing through the African American neighborhood where the killing occurred unearths a blind boy who heard the violence taking place, but his version of events will be hard to confirm. “Eyewitness” concludes—as do other early Harry O entries—with justice having been served, but victims no better off than they were hitherto.

In a final standout, “Shadows at Noon,” Harry discovers a strange young woman has broken into his home, which he isn’t in the habit of locking. Her name is Marilyn Sidwell (Diana Ewing), and she’s escaped from a mental institution, but insists she’s sane and is being held against her will. After she’s sent back to the sanatorium, Harry commits himself voluntarily to that same facility, hoping to determine the veracity of her claims…only to learn that he’s been betrayed, and can’t get free again. As this yarn progresses, questions of sanity are raised and proof of a conspiracy is established. Still, in the end, Marilyn—with whom Harry has begun a warm association—is reinstitutionalized. As hard as Harry tried, he couldn’t save her.

“I felt like screaming,” he told the audience. “But I didn’t. You can get into a lot of trouble screaming. I decided to run instead. It didn’t do much good. I did another thing that didn’t do much good either. I locked the door to my house. Not that I was worried about anyone trespassing. I just liked the feeling of having a key in my pocket.”

While the program’s nuanced plotting and downbeat air impressed viewers steeped in noir storytelling, it left ABC honchos clutching their worry beads. The costs of shooting outside of Hollywood were mounting, and Harry O’s solid but unspectacular Nielsen ratings made them hard to justify. A makeover was soon dictated, the most obvious result being the series’ relocation from San Diego back to smoggier Los Angeles, with Orwell evidently reoccupying the humble beach abode he’d had in Smile Jenny, You’re Dead. (That cabin was said to be located in Santa Monica, at 1101 Coast Road, but was in fact sited at Paradise Cove in Malibu—the same area where Rockford parked his trailer home.) In other concessions, car chases and gunplay were peppered into Orwell’s escapades; his health infirmities were de-emphasized in favor of physical action; his Austin-Healey finally ran consistently enough that he could give up bus riding (though a clip of him deboarding a San Diego local lingered in the opening title sequence); and his narration became less introspective and more about advancing the plot.

Before Charlie’s Angels, Farrah Fawcett-Majors (right) had the role of Orwell’s flight attendant girlfriend, Sue Ingham.

Before Charlie’s Angels, Farrah Fawcett-Majors (right) had the role of Orwell’s flight attendant girlfriend, Sue Ingham.

What’s more, the P.I. got a steady girlfriend in the form of Farrah Fawcett-Majors (then in her late 20s, and known primarily from hair-case commercials). She played Sue Ingham, one of sundry curvaceous—and oft-bikini-clad—airline stewardesses renting the house next to Harry’s. Sue didn’t have a large role in the show, and Orwell wasn’t totally faithful to her; but she did manage intermittently to tease out Harry’s lighter side.

Scripts struggled to accommodate this jiggering. “For the Love of Money” imagined Orwell representing a woman who’d conspired with her boyfriend to “borrow” $25,000 in bonds from her boss’ safe…only to change her mind and try to give them back. Trouble was, by then her lover and the loot—now said to be worth $500,000—had both disappeared. In “Silent Kill,” a deaf young woman (Kathy Lloyd) asked Harry to investigate a deadly building blaze blamed on her deaf mute husband (James Wainwright). It was a fairly sweet saga, but heavy-handed messaging about disabilities made it less affecting. “Lester” sought to recapture the comedic élan of “Gertrude,” reintroducing Les Lannom from that episode as Lester Hodges, a brilliant and wealthy young would-be criminologist accused of perpetrating college-campus “sex murders.” (Hodges proved entertaining enough—with his bungling, mistimed grinning, and immoderate adulation of Orwell—that he returned in three Season 2 stories.) And then there was “Elegy for a Cop,” a doleful tale that repurposed footage from the 90-minute version of the initial Harry O pilot. “Elegy” had Manny Quinlan motoring north from San Diego to rescue his doper niece in L.A., only to be gunned down and set up as a corrupt copper for his trouble. It fell to Orwell to clear his name.

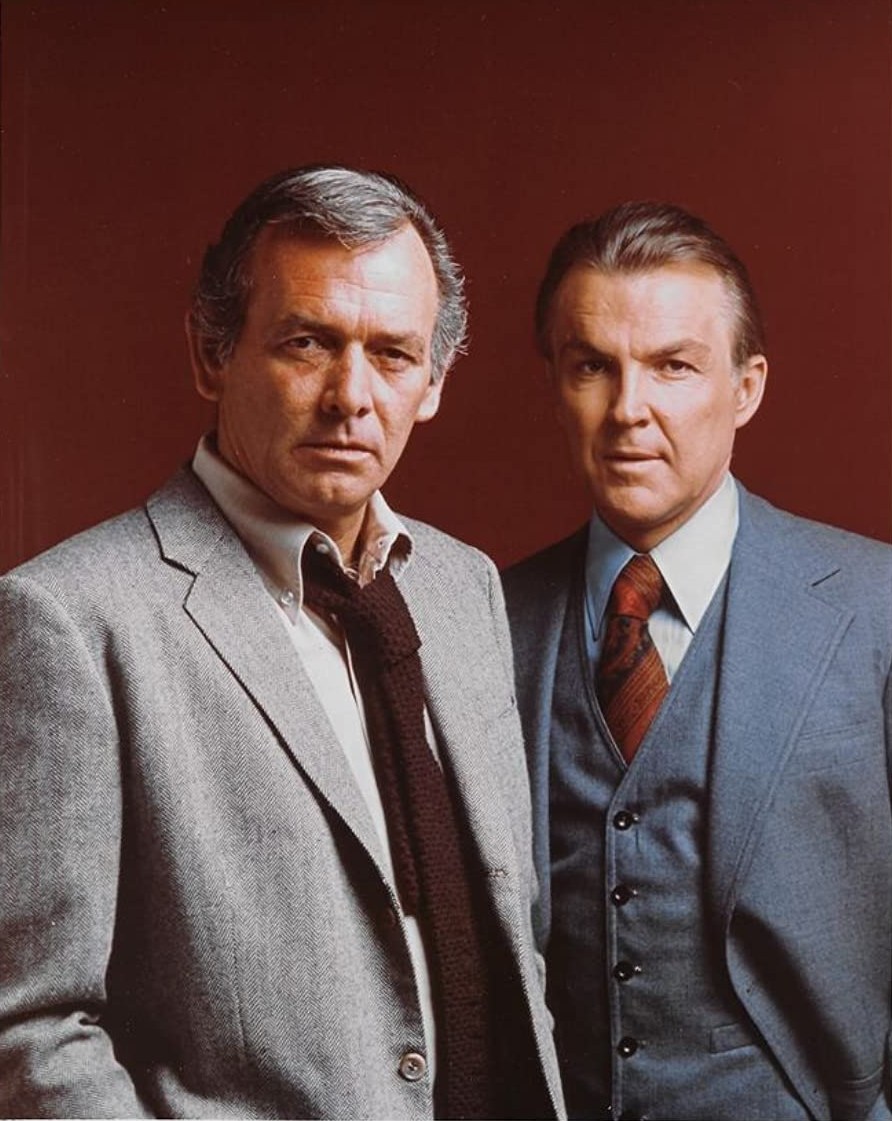

Anthony Zerbe (right) joined the show partway through Season 1 as Santa Monica cop—and regular Orwell foil—K.C. Trench.

Anthony Zerbe (right) joined the show partway through Season 1 as Santa Monica cop—and regular Orwell foil—K.C. Trench.

Fortunately, by then Harry had recruited another law-enforcement contact: Lieutenant K.C. Trench of the Santa Monica Police Department, portrayed by Anthony Zerbe, known to telly enthusiasts for having brought numerous guest villains to life. Rodman (whose influence over the series waned after its return to La-La Land) had conceived of Harry O as a character-propelled drama, with his P.I. the predominant focus. Nevertheless, Zerbe’s Trench—hard-nosed, opinionated, and smartly besuited (like Quinlan, he seemed to dress in explicit protest of Orwell’s yard-sale wardrobe)—quickly became a brilliant foil, a hot-shot cop who respected Orwell’s instincts and ability to understand people, but was impatient with his flouting of rules, and bristled each time Harry helped himself to his office coffee—only to promptly deride its palatability.

Listening to some of that pair’s exchanges, one might deduce they were sworn adversaries. Au contraire: their sniping in fact concealed a durable brotherhood. “So, Orwell,” remarked Trench, surprised when the dropout detective turned to a high-profile bookie for aid on a case, “I thought you always worked alone.” “Only when I work with you,” Harry retorted. And at the end of an episode in which the sleuth rescued Trench from a hostage situation, the cop said, begrudgingly, “I probably should thank you, Orwell. You may have saved my life.” “Well,” groused Harry, “I didn’t do it on purpose.”

Los Angeles author/screenwriter Lee Goldberg commends Trench as “the best ‘friend on the force’ in TV P.I. history.”

By the time Harry O kicked off its sophomore season in September 1975—complete with an uptempo revamping of Billy Goldenberg’s theme—the relationship between peeper and policeman was smoothly honed. Murder on the Air says, “it was the acting sparks of David Janssen and Anthony Zerbe which kept the show artistically afloat during its hard times.” For his endeavors, in 1976 Zerbe would pick up an Emmy for Outstanding Continuing Performance by a Supporting Actor in a Drama Series.

* * *

This show may have shed a share of its original unconventionalness and compelling darkness in favor of melodrama and happier endings; and like other 20th-century network programs forced to churn out more than 20 episodes every year, Harry O now and then issued clunkers (including two—count ’em, two—Agatha Christie-esque stories about family members trying to off one another). Still and all, Season 2 furnished a number of distinctive yarns.

In “Anatomy of a Frame,” Orwell helped Trench disprove allegations that he had murdered an informant. The lieutenant soon returned that favor in “APB Harry Orwell,” which saw the snoop being fitted for a homicide rap by a paroled bank robber he’d put behind bars years before. (In a clever finishing twist, Orwell was flummoxed by the ex-con having stewed for so long over his incarceration, as Harry had no recollection whatsoever of working his case.) Once again dealing with mental health issues, “Portrait of a Murder” dispatched Harry to scrutinize a string of stranglings, ostensibly committed by a developmentally disadvantaged teenager (Adam Arkin), who contended that a “lion” was to blame, instead. And if prosaic in other respects, “Reflections”—wherein Harry helped his ex-spouse, Elizabeth (Felicia Farr), overcome blackmail threats—at least afforded us a peak into our hero’s history as a husband and cop. (It also found Harry’s car conking out in the midst of his tailing a suspect—not your typical crime-show turn.)

“Exercise in Fatality” tasked the shamus with both “a wandering daughter job,” as Hammett would have put it, and the protection of a former lover—the latter of which left him so enraged, he almost croaked a pusher’s enforcer. (“To this day, I don’t know if I would have killed that man,” Orwell intoned, “but I do know I came close, and that in itself is very frightening.”) Finally, in the outlandishly plotted but amusing “Mister Five and Dime,” one of Lester Hodges’ classmates (Glynnis O’Connor) turned to Harry after being implicated in a bogus-currency scheme. The P.I. then solicited Trench’s back-up—only to embarrass the lieutenant before one federal agency after the next.

Harry O appeared to have survived efforts by ABC suits to make it a different sort of detective show with no differences at all. There was cautious optimism about it winning a third season. There were even hopes of spinning off a new series, partnering Lester Hodges with a celebrated criminalist played by Kung Fu’s Keye Luke.

But as various sources tell it, the show was doomed by the hiring of Fred Silverman as president of ABC Entertainment in 1975. Silverman was reckoned something of a wunderkind. After his years spent overhauling programming schedules at CBS, and witnessing that network’s consequent rise in fortunes, Silverman vowed to bestow the same magic on ABC. “He was looking for shows that he thought had the potential to be runaway hits,” Jerry Thorpe told Television Chronicles. “He didn’t want to settle for the ‘average.’” And Silverman thought Harry O was merely good, with limited prospects for audience growth.

The final fresh episode of Janssen’s fourth crime drama was broadcast on April 29, 1976. Silverman cancelled the show, together with a spate of other prime-time regulars, to make room for blockbuster-wannabes and such “jiggle TV” eye-catchers as Charlie’s Angels, co-starring Farrah Fawcett-Majors—who he’d become familiar with thanks to her scenes on Harry O.

David Janssen, who had invested so much of himself into Harry Orwell’s success, went on to make teleflicks such as S.O.S. Titanic and the better-than-average Golden Gate Murders, as well as the NBC mini-series Centennial, based on James A. Michener’s epic of that same title. He died from a massive heart attack in February 1980, at 48 years old. He never did star in another weekly series.

Not until the early 2010s did Harry O finally see a DVD release. While other mid-1970s crime shows have aged poorly, Ed Robertson says Harry O “holds up very well….The humor holds up (especially in the scenes between Janssen and Zerbe), and Harry remains someone whose adventures you like following, 60 minutes at a time.” Orwell wasn’t a perfect protagonist, but unlike myriad other small-screen gumshoes, he didn’t seriously test the bounds of plausibility. He was a low-key fellow, grapping with inner conflicts; “an irascible and contrary man with very little in life to care about, who nevertheless cares very much,” as The Thrilling Detective Web Site describes him. Janssen played this unremarkable man remarkably well.

I won’t go so far as Robert Randisi does, to suggest that Harry O outshone The Rockford Files as a classic TV private eye production. But it probably does merit second-place honors. Who knows how much better remembered Janssen’s series might be nowadays had it remained on the air long enough to gain a surer footing.

It says a lot, don’t you think, that although I only recently rewatched Harry O in its entirety, I’m nearly ready to start all over again?

Please pass the remote.