“There was no call for him to be as unkind as he was,” says famed author Patricia Cornwell, who single handedly created the forensic science crime fiction genre.

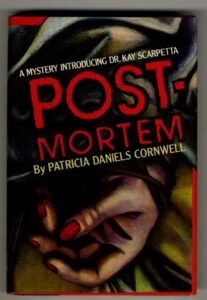

Robert Merritt, the theater and arts critic for the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1989, trashed his fellow Richmonder’s first crime novel, Postmortem, calling her protagonist, Medical Examiner Dr. Kay Scarpetta, a whiner who complained about male chauvinists who obstructed her way to the top of her profession. She was also an unlikeable divorcee with a big ego—something, one must surmise, women weren’t allowed to be or have in the 1980s.

“It’s far removed from a mystery-loving Agatha Christie, and more attuned to unexplained scientific acronyms and gruesome bodily details,” Merritt wrote. He concluded his review noting, “If Postmortem has a glimmer of a promising debut, it’s in the author’s insights into the reality of crime.”

Postmortem was Cornwell’s fourth attempt at publishing a novel and now she was being trashed in her hometown newspaper. Even the local bookstore, Volume One Books, refused to carry her new novel because of its graphic content—content not seen before in crime fiction. And even though she used part of her $6,000 advance from Scribner’s to print and post handbills promoting her first signing at Cokesbury Books, nobody came.

“Between the banned book and the newspaper review, I didn’t think it could get any worse,” she says. After three failed publishing attempts and one disaster of a debut, the little-known author considered calling it quits. “I thought I’d end up as a computer programmer. I wouldn’t stay in the morgue forever because I just went there to learn. I’d seen things that most people never see and that changed me.”

But a month later something happened that transformed everything. Charles Champlin, arts editor for the LA Times, read Postmortem and told the world how much he loved it. The bicoastal reviews punctuated the sharp contradict between Richmond, the former capital of the Old South where change crawled at a turtle’s pace through the faded pages of its revered uppercase History, and Los Angeles, the capital of entertainment, which created change on an hourly basis. Things were about to redefine Cornwell’s life and crime fiction forever.

A glimmer? Merritt missed the mark by decades—a hundred pages of History. Cornwell’s Postmortem changed everything. The crime novels you read, the movies you watch, the television series airing nightly—all of those crime scene investigation stories started with Postmortem.

Cornwell did not get rich on her first novel. Scribner’s failed to print enough copies. Even after several printings, there were still only 10,000 hardcovers in existence, which shows how little confidence her publisher had in Cornwell’s groundbreaking novel. Thanks to that hesitancy, a Postmortem first edition today makes for quite a treasure. And because of the small press run, Postmortem is the only novel in Cornwell’s long career to fail to hit the New York Times bestseller list.

But it hit everywhere else. It was the first novel to ever win in the same year the UK Crime Writers’ Association John Creasy best first novel by a previously unpublished writer, the Mystery Writers of American Edgar Award for first novel, and the French Prix du Roman d’Aventure prize.

In spite of Merritt’s failure to recognize modern social mores and his uneasiness with a single woman’s ambition and point of view of men, Cornwell had arrived as the next big thing, even if her royalty checks would take their time catching up. Hers is a journey of discovery—especially about herself, she says—but it’s also a story of tenacious curiosity and drive.

It wasn’t until college she decided she wanted to become an author. “When I graduated from college, I knew I wanted to write books. I wasn’t good at anything else.” So, she got a job at the Charlotte Observer updating the newspaper television magazine programming grid, and quickly worked her way up the ladder.

“I was picked to be a night police reporter, which I thought was dreadful. I worked Sunday through Thursday nights, and I was engaged at the time, so I didn’t see much of him.”

She soon realized, “I took to crime investigation. I clearly had some aptitude for it.”

Each evening after making her police rounds and visiting the latest crime scene, she would return to the newspaper to write her stories. Across the street she noticed prostitutes sitting on a wall. In the middle of the night, she struck up a conversation with them and later their pimps. “I was so fascinated. I was so curious.”

In her first year as a reporter, she won the Carolina Press Association’s Investigative Reporting Award for her series on prostitution.

She then moved to Richmond, Virginia with her new husband, Charles Cornwell, where he was studying at Union Theological Seminary to become a minister. There, Cornwell, began writing a biography of Ruth Bell Graham, best known as the wife of famed evangelist Billy Graham, but also his business adviser and author of 13 books.

Ruth had taken in Cornwell at age nine, several years after her father, famed appellate lawyer and Supreme Court clerk Samuel Daniels, abandoned his family. Marilyn Daniels moved her clan in 1963 from Florida to Montreat, North Carolina where she was later hospitalized for mental illness. Cornwell turned to Ruth for guidance. It was Graham who recognized Cornwell’s writing ability and encouraged her potential.

Her Graham biography was published in 1983 and Cornwell began considering her next move. She started writing crime novels. As a former police reporter, she always wondered what happened to the bodies after the police were done with their investigation.

“I had a friend who knew Dr. Marcella Fierro and he managed to arrange a tour at the state medical examiner’s office. She saw no bodies during her tour, but Fierro explained how DNA was rapidly becoming an important forensics tool for investigations. But this didn’t answer Cornwell’s curiosity about autopsies. Fierro told her she would need some legitimacy before Cornwell could ever observe an autopsy. So, the young author became a volunteer police officer and the next time the two met, Cornwell was dressed in her police uniform.

She observed her first autopsy with several other officers. “The first autopsy was surprisingly benign.” That’s because it was done on an elderly person who had died alone but not under a doctor’s care. When that happened in Virginia an autopsy was required. Fierro and her office were judicious about the types of cases they allowed people to observe. “She would never do an autopsy on a homicide victim as a demo autopsy,” Cornwell says.

And how did cutting up a human being affect her? “Fierro said try to focus on what she is looking for instead of getting involved in the gore,” Cornwell says. “I did fine with it.”

“You think you know who you are by the time you graduate from college, but you don’t. I did not know who I was. I discovered I had an aptitude for this,” she says. “It does seem surreal. I think this is true of most things in life. I never intended to start anything. I just wanted to write a story I could tell. I really thought I would write a police procedural and then the morgue took over.”

Fortunately for her, she began doing research in the medical examiner’s office, and was later hired as a technical writer, and then computer analyst. She worked there for six years to learn all she could about forensic science. During this time, Cornwell wrote three crime novels, all rejected. So, in the late 1980s she shifted her focus and tried a new protagonist, Medical Examiner Kay Scarpetta.

One day at work she was asked if she’d like to attend an open house for a new morgue for the Dade County Florida medical examiner’s office since other staff had scheduling conflicts. There, she met famed Miami Herald crime reporter Edna Buchanan, who had published nonfiction crime books, the most famous of which was The Corpse Had a Familiar Face: Covering Miami, America’s Hottest Beat.

“I ended up riding around with Edna for the better part of a day, and she gave me the name of her agent. If it hadn’t been for Edna, I would not have had an agent.”

Well, she had in the past, but neither of her previous agents wanted to work with her. Her agent for the Ruth Graham book was not interested in fiction and her second agent abandoned Cornwell when she couldn’t sell her first three novels.

With Buchanan’s help, agent Michael Congdon took Cornwell on as a client and she handed him her fourth crime novel manuscript, which she named Postmortem. Cornwell made a lot of his suggested edits, which sped up the plot. They followed that up with eight months of rejections, “from every major publisher you can think of,” Cornwell says. And then one day the light flashed on her answering machine at work. Congdon left her a message that Scribner’s had made an offer. In her excitement, she rushed downstairs to tell anyone she could. “I’ll never forget talking to one of the medical examiners and he said, ‘that’s nice’.”

So, she left the office early to celebrate on her own.

Scribner’s Editor Suzanne Kirk didn’t ask for a lot of changes and the novel finally came out in January 1990. The previous month, Merritt had published his scathing Postmortem review in the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “I call him Robert de-Merritt,” Cornwell says, still smarting from the rejection decades ago. But after the L.A. Times review, her once dormant phone had begun to ring nonstop.

And then Congdon called with a most unexpected announcement. She’d won the John Creasy Award from the British Crime Writers Association for best first novel, and Princess Margaret was going to be handing out the award.

She was still young, had little money and was about to meet royalty. She needed a dress. So, she found a fancy clothing store on Cary Street, a popular area near downtown Richmond.

“I couldn’t get any help because I didn’t look like I belonged,” she says. After finally getting a clerk’s attention, Cornwell told her she was going to be meeting royalty and needed a proper dress. “Suddenly, she brought out this wooden box for me to stand on and they started bringing out all types of sequined and beaded tops and dresses. They even taught me how to curtsy…I felt like Ma Kettle goes to the big city.”

The day of the presentation, her publisher took her to a London wine bar. Not meaning to, they stayed the afternoon. They finally returned to the hotel to dress for the ceremony and Cornwell realized she’d never put on her new beaded top without someone to help zip up the back. Alone in her hotel room, she couldn’t get the zipper beyond her waist. Desperate for help, she opened her hotel door and saw a man walking down the hall. She begged for his help. He obliged and she quickly shooed him out of her room, not wanting him to get the wrong idea.

Fortunately, when they arrived for the event, they realized they weren’t the only ones who had been drinking that afternoon. Princess Margaret had been tipping a bottle of Scotch, “so we were all very well lubricated.”

The Princess, Cornwell said, “was very charming and nice.” Backstage after the presentation, Margaret asked Cornwell how long it had taken her to write her novel. About a year, she told the Princess. Not wanting to let the conversation lapse into uncomfortable silence, Cornwell asked the Princess about horses. She mistook Margaret’s fondness for horses for another royal, the Queen. But that wasn’t the issue. Just asking the question was a royal no-no. Quickly, a red-coated British guard escorted Cornwell away.

“If there ever was a hook moment, that was it,” Cornwell says with a laugh.

Today Cornwell says she looks back at her beginnings with affection. She had little money, unlike now. “It was an early time, and I didn’t know what it would be like today…It was an evolution and journey and a series of accidental things.”

“I was just a hair away from never getting anything published. I had had three manuscripts fail. If this had failed, I don’t know what I would have done.”

As she looks back, she remembers a necklace she bought with a blank charm, no inscription, as a metaphor for her beginnings. “I felt like a blank slate, alright.”

Or was that the first glimmer of a promising debut?

___________________________________

Postmortem

___________________________________

Start to Finish: 1 year (My whole life!)

I want to be a writer: Realized in college. Before, I didn’t want to be a writer, but I was one.

Decided to write a novel: 1984

Experience: Three unsuccessful crime novel attempts. Nonfiction book about Ruth Graham, reporter at Charlotte Observer

Agents Contacted: dozens

Agent Rejections: dozens

First Novel Agent: Michael Congdon

First Novel Editor: Suzanne Kirk

First Novel Publisher: Scribner’s

Age when published: 34

Inspiration: The real people who do the real work.

Website: PatriciaCornwell.com

Advice to Writers: Don’t just Google it. Figure out what makes you curious and fills you with wonder and go out and find it.

Like this? Read the chapters on Lee Child, Michael Connelly, Tess Gerritsen, Steve Berry, David Morrell, Gayle Lynds, Scott Turow, Lawrence Block, Randy Wayne White, Walter Mosley, Tom Straw. Michael Koryta, Harlan Coben, Jenny Milchman, James Grady, David Corbett. Robert Dugoni, David Baldacci, Steven James, Laura Lippman, Karen Dionne, Jon Land, S.A. Cosby, Diana Gabaldon, Tosca Lee, D.P. Lyle, James Patterson, Jeneva Rose, Jeffery Deaver, and Joseph Finder.

If you were a subscriber to Rick Pullen’s Idol Talk newsletter, which dishes on your favorite crime novelists, you haven’t received a copy recently. The website crashed and the subscriber list went down with it. Idol Talk is now on Substack to assure smooth sailing. If you’d like to ride along again, please resubscribe (or subscribe for the first time) at rickpullen.com.